- The Ministry of Special Cases

- Knopf (2007)

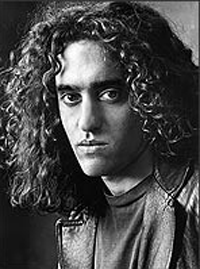

Nathan Englander was born and raised in an orthodox Jewish community in Long Island, New York. His first book, a collection of short stories that centred on the lives of the New York Hasidim, was published eight years ago to almost universal acclaim. But in the near decade since, nothing: not so much as an essay, let alone a new story, was published under Englander's name.

Now, finally, after living through the second Palestinian intifada in Jerusalem, only to move back to New York just weeks before Sept. 11, Englander has returned. And while his debut novel escapes the physical settings of both New York and Jerusalem, it is, in many ways, wrapped up in the ideas of both them.

The Ministry of Special Cases takes place in the Dirty War of the Argentine 1970s when a military government used an internal war against dissidents to justify mass arrests, torture and the "disappearing" of thousands of student activists. Parallels to the current "war on terror" seem obvious. But, for Englander, the focus is less political than metaphysical.

Last week, the still young writer, fresh off the plane from San Francisco, spoke to The Tyee at a coffee shop just outside Vancouver's art gallery in the downtown core. Over black coffee and a blueberry scone, Englander spoke about Jewish identity, tenuous reality and how to read his book. Below are excerpts from that conversation.

On why Seymour Hersh appears in his acknowledgements:

"For me, I'm obsessed personally with the idea of the grey. Having been raised religious, the black and white of the world, it's like the whole world is grey. And then there's this article "The Gray Zone," (a New Yorker investigation of the Abu Ghraib scandal) that just has a very specific idea of people being brought back in to the white world. When I knew that I'd absorbed that directly, it inspired actual thought, I knew I had to acknowledge it.

"Listing the article was not a political statement.... I didn't build Abu Ghraib."

On how the last turbulent decade affected his writing:

"The point is, I had my novel. And as I'm telling it the world is changing. So yes, the second intifada changed my life. And moving back to New York, writing after Sept. 11, all of that, the American reaction, all these things, fed in. It's not a political novel to me, but there's no way those ideas didn't feed in.... There's no way that living in those two cities didn't feed in, but it's not a conscious feeding.

"It's really weird to spend a decade on something. A novel needs to be this seamless unbroken dream. It's the only way it should be.... That idea that you've written the front one year and the end eight years later, you're still constantly rebuilding and making sure that tonal consistency exists."

On whether his book should be read as a commentary on current events:

"I'm not thrilled that it has any link. I can't believe that America's messing with habeas corpus or things like that; you know, that people are being sent to third party countries. But again, I think that's what books are supposed to do and I'm glad if it's functioning in that way. But I'm not glad that my metaphor is no longer metaphorical, it's crazy.

"My obligation is to the text. Not even the text, the novel itself. So I always feel like I don't matter. But it's just that idea that it doesn't matter if I set out to write this book and I tell you that to me this book is about the potato famine. I can think that and have written this entire book in Argentina and think it's about the Irish potato famine. What I think doesn't matter. Like I said, if it ends up being political, great. If I tell you it's about identity and someone says it's about fathers and sons, it's like, 'oh yeah.' Like if I have a political view and weave that in, it ruins it. The only things that can stay are those of this world."

On why he chose to write about Argentina:

"If I'm interested in the life of the individual in Jerusalem, I'm living in Jerusalem, I just want to be a regular guy, I want to walk to my coffee shop, write my book and walk home and not get blown up and that's it. And you start to say, 'Well, do I have a right to want this? Does the government have a responsibility to provide this? What is it to even have this individual life when there's the military problems, the government problems, you know, violence this, the Palestinians, the Lebanese.'

"That's one story, [the other is] what is it to love this very complicated city?

"You know, I was describing it, like we always complain about the weather in Vancouver, it's a pastime. It's that idea, you know, we'll all be like, 'I hate my neighbours,' and 'I hate this' and 'I hate that.' But then everyone is so deeply dedicated to the city and you're like, what is it to love these places that betray you or what is it to love a place if you want to claim you hate everything about it? Is it the dirt?

"So when I started looking into Argentina, I thought, what better place to talk about love of city and government betrayal and this tragic set up that they have there."

On writing someone else's city:

"I saw everything coming down the block here because I've never been to this city before. You know, a million things, like the busses are connected to wires. You know if you said, 'Let's take the bus,' I would say, 'Let's take that bus that's connected to the wires.' That's not what someone from Vancouver would say. That's normal. That idea that I notice that, that makes me an outsider, that's a weakness of research if you show it in that way. In a way, I wrote this whole Argentina, then I removed all this stuff.... So in terms of owning the city, I feel like I have an enormous number of weird factoids in my head and I removed them all in a weird way."

On 'disappearing,' quantum physics and tenuous truths:

"I was very aware of this quantum mechanical structure in physics [when I was writing], almost the Schrödinger's cat idea. There's a box with a button, it's a machine. You put a cat in that box, you can't see it, you press the button to turn it on. And what this machine does, it kills the cat exactly 50 per cent of the time. So when you press that button, until you open the box again, the cat is both equally alive as it is dead, it's in two realities. Once you open it, you'll have an answer, but until that time it is on two planes of existence.

"This idea of disappearing actually reaches into the future, like someone is never going to be. They are not in the moment, but they weren't ever. It's like altering the time-space continuum. And that's the idea, you know, in the novel, the line, 'How true is anything that only one man believes?' Is it enough, one man believing otherwise to undo that? If nobody says anything when these things happen, does it make truth?"

On the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo:

"These mothers organized in the 70s and march every Thursday still. To me I actually think of them as heroic in a way, but I actually think, it's almost like a physics experiment. The government they've been fighting against has been gone for 25 years. You know, this started 31 years ago, this coup. Why would they march now? They know their kids are dead. The government's gone. Like, what's the point in marching every Thursday, unbroken, now?

"It's because when these people said their kids were gone, they said they had to march every Thursday until each of them dies, which is what they're doing. I feel like they're making an unbroken thread in the time-space continuum that keeps their kids alive even though they're dead. I feel in a very deep way that these women are anchoring this whole separate history and future, that they've kept their own thread. To me it's unbelievably miraculous and heroic."

On being Jewish and a writer but not a 'Jewish writer':

"I'm very thankful for the reception of the first book. You know, literary fiction about Hasidim, I didn't expect to have this whole life from it. [But] I fought it with the second book. Because you want to do something different....

"I was so resistant to these labels that get put on people, like now I'm a Jewish writer. I just tell my stories. It has nothing to do with any of that. And I feel like I almost kept the Jewish stuff out of this book. In the end, it was almost like a comfortable moment for me when I finally said -- you know the first line of the book, 'Jews bury themselves the way they live'? -- I'm just going to start with the word Jews and get it over with. It was like an epiphany moment. You know, let's just get this out of the way. If you can't get past that first 'Jews,' then just close the book now."

On writing and resisting who you are:

"We're born into a home. Whether that home is two parents, or one, or three, or an orphanage, or you were raised by wolves, we get our brains patterned to see the world in a certain way. And I was raised in an orthodox closed community. For me, the whole world, the whole complete universe, the entire world history, I learned through the Jews and was about orthodox Jews.

"So for me, it was actually freeing when I said, if my head sees things this way, that is the complete universe of my imagination, as long as that universe is a universe, as long as it's gaining wisdom and expanding, then that's fine. You know, it's not how I am personally, but for some reason in this book, that's the point of view. And when I let that in, it was actually freeing....

"But that pressure from within, from the community, you know, 'You're a Jewish writer and you're one of us,' actually made me want to change the way my mind works. But now I'm totally comfortable. If all my books are about Jews, what do I care? Cause they're about my people, and I don't mean 'my people,' I mean the people that inhabit my brain."

On the message he'd give to potential readers:

"I put everything I have into this book, and I feel like that's what really does the speaking for me. I don't know about the pitch part... (laughs and says in the voice of a TV ad) 'If you like Jews, you'll love The Ministry of Special Cases.'"