Recently while visiting Toronto, I went for breakfast with an old friend, W. Among our circle of friends from university, W. was the first to reach each ascending milestone of adulthood. W. was the first one to get married; the first to buy a house; the first to have a child; and then the first to have his second. This time, as we ate banana pancakes and peameal bacon for breakfast, I learned he had become the first to have a vasectomy.

W. and I both prefer to speak freely. He paused while our waitress refilled our cups of coffee, before resuming his step-by-step account of the procedure. At one point, he made a sudden yanking gesture. "Now I know," he said, "why these procedures are so hard to reverse."

For some reason, the words of the U.S. poet W.S. Merwin rang in my head. "It sounds unconvincing to say 'When I was young,'" I said, recalling Merwin's "In the Memory of My Thirty-Eighth Year." "Though I have long wondered what it would be like / To be me now / No older at all it seems from here / As far from myself as ever."

But what I really said to W. was: "Does it hurt when you have a boner?"

That is a reply characteristic of an adultescent, an adult -- typically, a man -- who hasn't quite traded his childlike appetites for age-appropriate attitudes and tastes. It's this coinage used to describe the target demographic for summer blockbusters like Superman Returns and the Adam Sandler vehicle Click.

Last year's The Wedding Crashers, though, might have best captured the spirit of the adultescent. The film stars two actors, Vince Vaughn and Owen Wilson, whose careers have been built around a kind of joyful fecklessness. Though the film portrays the two crashers -- who sneak into weddings to meet women -- as romantics who love nuptial pageantry, a cynical explanation for the film's appeal might be that it could be enjoyed as a subversive, almost defiant, critique of the socio-economic forces that cajole and shame men and women of a certain age into emptying their savings accounts for a four-tiered cake.

Hollywood fantasies are all strangely puritanical, and The Wedding Crashers eventually renounces its pleasures. (The underlying message to the audience from Hollywood is: Don't resent us because we're rich and gorgeous; pity us, because true happiness is working minimum wage and owning many DVDs.) The Owen Wilson character grows tired of crashing, reflects sombrely, and turns his life around.

Although the adultescent is only a recently recognized phenomenon, I would suggest that he appears, fully developed and unapologetic, in literature. Unlike the fledgling movie adultescent, its literary cousin doesn't so much make amends for his inability to grow up but justifies it -- draping his stance with philosophy, rationalizing it as a political statement and as an indictment against the infantilizing neuroses of an entire culture, or masking it in fabulism and sophistry. The controversial writing of Michel Houellebecq, for instance, essentially defends sex tourism as a way of righting the hypocrisies of western culture -- which promotes sex for all but denies it to the poor and ugly. The megalomania of the artist, you see, is compatible with adultescent's imperative to feed the need. (In France, Houellebecq was charged with -- and later cleared of -- inciting racial hatred against Muslims. Houellebecq successfully defended himself by arguing that he was derisive of the Islamic faith itself and not its followers.)

Of course, the more celebrated type of literary man-child is the Peter Pan figure. The key difference between this archetype and the adultescent is that the latter not only wishes to play video games but also wants to have sex (i.e. with other consenting adults); he isn't caught ambiguously between adolescence and adulthood, he merely wants the privileges of both.

Despite the enduring presence of this archetype, there's something resoundingly creepy about someone who refuses to grow up because he wants to retain the innocence of childhood. Writing about one of the most popular iterations of such a character, Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye, novelist Tom Perrotta observed in the New York Times: "In his neurotic fragility, his idealization of childhood and his horror of profanity, Holden didn't resemble anyone I'd grown up with." In other words, how many people do you know who are like Michael Jackson or Salinger? And how many grown men do you know who collect comic books and own Lord of the Rings on DVD?

Children have always wanted to grow up as quickly as possible and today they succeed -- Internet and television filters are easily dodged -- at an unprecedented level. And yet, as they grow up, most will find the privileges of adulthood come with a worldview that includes finding pleasure in a nicely mown lawn and promptly filed tax return.

Here, for your late summer reading edification, is a selected list of books that feature adultescents. All are worthy distractions. You can mow the lawn another day.

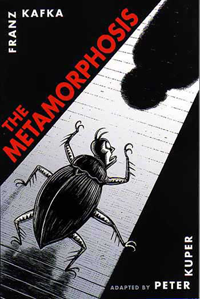

Metamorphosis By Franz Kafka This 1915 story's conceit -- a man turning into a giant bug -- obscures the fact that Gregor Samsa is a grown man who's unable to move out of his parents' house. Gregor feels he brings shame to his family, which grows increasingly hostile over the course of the story, confirming his suspicion. As Dr. Phil might point out, Gregor literally becomes what he already feels he is. (Kafka's story was the inspiration for Philip Roth's The Breast, in which a man wakes up as a giant mammary gland.)

A Fan's Notes By Frederick Exley Exley's 1968 novel is about a divorced, alcoholic former high-school athlete named Frederick Exley who's obsessed with Frank Gifford, then the New York Giants quarterback. "The Giants were my delight," says Exley, the character, "my folly, my anodyne, my intellectual stimulation." Exley's novel anticipated the superannuation of the fan and the growth of fan subcultures that are seen today.

High Fidelity By Nick Hornby A distinguishing feature of a specialized type of adultescent is the tendency to mistake one's hyper-discerning taste in obscure pop music with any palpable accomplishment. "It's not what you're like," says Rob Gordon, music aficionado and the hero of Nick Hornby's 1995 novel High Fidelity, "but what you like." Hornby both celebrates and satirizes the rock snob and his lack of mastery in aspects of life beyond making top-five lists.

Lenny Bruce Is Dead By Jonathan Goldstein Goldstein, host of the CBC show Wiretap, is one of Canada's funniest and most underappreciated writers. His 2001 novel is about a young man named Josh who works at a fast-food joint and returns to live with his father after the death of his mother. The book is a collection of jokes, vignettes and screenplay ideas unified by Goldstein's voice, which is engaging, warm and often fairly smutty: "In the theatre her mouth moved warm and sure right over you. In the darkness, while she worked, you thought you were making eye contact with some guy...You felt sorry for him."

Platform By Michel Houellebecq Houellebecq has griped that Western society "increase[s] desires to an unbearable level while making the fulfilment of them more and more inaccessible." His novels are typically elaborate wish-fulfilling scenarios: a nerdy, sex-starved guy with a boring white-collar job ends up enacting a porn-star fantasy. In this 2003 novel, the narrator, "Michel," finds fulfilment with Valerie, a nubile and sexually adventurous travel-tour executive. His plan to start a package tour for sex-tourists goes over well with Valerie and her boss until Islamic fundamentalists (Houellebecq has hate-ons for both hippies and Muslim extremists) harsh his buzz.

Those who don't share Houellebecq's strong opinions might still find his vitriolic, insult comedy amusing and a good launching pad for a thoughtful dinner-party discussion on the difference between French and North American attitudes toward sex and religion. Like all the books above, Platform allows grown-ups to indulge their inner adolescent without surrendering to it -- or to abhor the excesses of immaturity.

Kevin Chong is the author of Baroque-a-Nova, a novel, and Neil Young Nation. He can be found exercising his own inner adultescent at Bookninja's Wordwise.

Related links and Tyee stories: Lakshmi Chaudhry explores life as a perpetual adolescent in "Growing Up to Be Boys." Vanessa Richmond talks about young men and their feminine side in "The New 'Sofcho' Man." Wordspy asks "What does adultescent mean?" ![]()