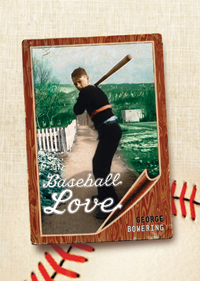

- Baseball Love

- Talonbooks (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

[Editor's note: George Bowering has written 10 novels, 25 poetry collections, and numerous books of criticism, history and anthology. He's won two Governor General's Awards for Literature, and was Canada's first Parliamentary Poet Laureate. Mostly, though, he just loves baseball, and Baseball Love chronicles that passion, from the Okanagan grandstands of the 1940s and '50s, through Vancouver's hippie Kosmic League of the '70s, to the minor league ballparks of the present. The following excerpt from chapter 4, "Growing Up in Baseball," recalls summers chasing errant balls around the Oliver stadium, where U.S. imports like Sibby would get a signing bonus, a job at the Esso station and a position in the infield, and where teenage girls would secretly place peanut shells on the fedora worn by the man in the bleachers in front of them.]

I never thought that baseball was a U.S. game. It was a birthright. And certainly it was normal. In the Okanagan sun, you got your baseball stuff out as soon as the ground got softer in, say, March, and you played the summer game till apple season was over in October.

The ballpark, with its big old grey grandstand made of obvious lumber, was the most important few acres in town. There was a sandy hill behind the grandstand. All along the south side, from back of the grandstand to past the left field foul pole, ran a huge wooden siphon that carried water from the east side of the valley to the irrigation ditch at the base of the hills on the west side. Out beyond right centre field was the Community Hall, with the scoreboard on its side. My friend Ronny Carter was the scoreboard boy. A lot of kids wished they could run along the gangway, putting up zeroes like that. Once in a while Cy Overton, the guy in the announcer's booth on the roof of the grandstand, would have to tell Ronny that there were actually two out, not just one.

"Two out, scoreboard," Cy Overton would announce so that you could hear it over the river and uptown, and Ronny would scramble.

My best pal Willy was not really a sports fan, much less an athlete, but we did just about everything together, serenading construction workers, developing pictures under his basement stairs, inventing clubs, building an airplane. Actually, we did partake in one athletic activity (besides the prodigious amount of swimming that any Okanagan kid does). We would save the little cardboard cylinder that one of the powders for darkroom chemicals came in, and using some badminton racquets, and the overhead power line as a net, engage in tennis games in the gloaming. Oh yes, and we invented a game called "economical ball," so titled because contestants sat in a circle of kitchen chairs and employed brooms in an attempt to roll a volleyball past one another.

Willy and I hung out at the baseball park, keeping track of the game and figuring ways to bring in some spending money while entertaining the crowd with our wit and musicality.

A popular way of getting rich was to retrieve foul balls and bring them back to the playing field for ten cents a shot. The trouble was that there might be thirty kids behind the stands, waiting for foul balls. You could acquire some pretty serious injuries back there, and I was rather disinclined to do all the running that such competition entailed. Once under the siphon I found a ball that must have been lying in the wet high grass for ten years. When I turned it in, they wouldn't give me my ten cents. So I told Willy that we were going to be hotdog vendors.

'Get your ice-cold franks!'

Between the huge siphon and the ball diamond was a long row of Lombardy poplars or cottonwoods or whatever they were, enormous pointy things, and sometime during the season, the white fluff would blow off in the wind from the hot south, and the sky would be full of cotton, white puffs, like snow in the middle of summer, drifting north, descending to cover Chevrolets, hiding the white baseball that sped at eighty-five miles an hour toward the plate.

Walking under this miracle that reminded us of something from the Old Testament, or just glistening in the still air of the Canadian desert, Willy and I were the hotdog vendors from Limbo. Back in 1949, they didn't have those thermal bags or coolers. We lugged pop crates and trays suspended from our necks. We worked the grey grandstand and the bleachers along the foul lines. We went from car to car. This was before they put up the professional-looking outfield fence with the advertisements for local businesses. There was a little lattice fence, and people would nose their cars up against it, sitting in their soft seats and taking in a game as if this were a drive-in theatre.

There was no air conditioning in the Okanagan Valley in 1949. All car windows were open. All car doors were ajar. Men did not wear shirts in the Okanagan, not after May and not before October.

"Ice-cold hotdogs," I would yell in my voice that was changing. "Get your ice-cold franks!"

"Red-hot soda pop," Willy would chime in. "Nice warming soft drinks right here!" We never planned on doing this for very long.

We were stocking up experiences for the movie we were going to make once we got our airplane aloft.

For Willy all this ballpark stuff was just more of our childhood buddy business. For me it was a lot more. Anything to do with baseball had that extra gleam, that magic -- no, that is some hack's word -- that oh god this is so sweet feeling that would not be there later, save in memory, that feeling that was also there when you got your Dick Tracy button with that yellow out of the Bran Flakes box, or the new Silvertip book by Max Brand at Frank's pool hall book rack, and if you can locate another nickel you'll have twenty-five cents, and kids under eighteen didn't have to pay sales tax.

Damn, I will never be able to describe the specialness of some experiences, and I can only hope that you have had something like that in your life and know what I mean, and you will be happy that I seem to have had it too, but there's no way we can find out for sure, though we have had the experience of catching another listener's eye when John Coltrane starts to wail.

Remember that pesky problem you had as a kid? What if your red is what I see as my blue, but of course we call it red because that is what someone told us it was when we first saw it?

Humour works that way, too. It can give you hope that you are not alone in this world with the horizons so far away. Else why write books? Still, there are going to be things in your book that no one will get, no one ever.

My buddy Willy's kid brother Sandy recently told me to put Squeaky into my book. Squeaky was, I guess, the town drunk in Oliver. He looked and sounded like Gabby Hayes, and he never missed a ball game. At Christmas he went to church and fell asleep in the pew. While the choir was attempting a carol, Squeaky would wake up and sing, "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

High on the tarpaper skybox

When I first got to Oliver, the Oliver Elks were in an international Okanagan league that included teams from south of the border—Omak, Tonasket, Chelan, Riverside, and teams from north of the border—Vernon, Kelowna, Penticton and Oliver.

I don't know why, but after a few years the U.S. teams were only around for exhibition games; they were replaced by teams from Trail, Summerland (the Macs, starring the three Kato brothers), Princeton and Kamloops. I think that the Princeton team dropped out when a big Ontario beer company bought the Princeton Brewery and closed it.

In a book called A Magpie Life I have told the story of how I took away my father's job as scorekeeper and newspaper reporter for Oliver baseball. I would love to find an original example of my reportage and insert it here, but I had to cut out the stories, measure them, and take them to the paper for my fifteen cents an inch.

I felt pretty important when at last I could tuck my scorebook under my arm and climb up through the trap door in the roof of the swaying grandstand, walk to the front of the roof, and stoop to enter the little tarpaper skybox there, where I would join Cy Overton, the public address announcer, and the visiting scorekeeper from the Vernon News, say.

I was as professional as all get-out, which is more than I can say about Cy Overton, a grown-up with thinning hair. Mr. Overton did not really comprehend the difference between a PA announcer and a play-by-play man. "Foul ball," he would say, and I would roll my teenage eyes.

Like my dad before me, I was inclined to assess an error rather than a base hit when a slow ground ball bounced off both the shortstop's ankles and rolled into shallow left field. There were a lot of times when Richie Snyder, the Oliver third baseman, got in my face about a dent to his batting average or an error I gave him for throwing the ball over the chicken wire behind first base. Richie was a bit of a whiner, but he was a pretty good ballplayer. I never liked him much. When I was a pinsetter he used to fire his five-pin bowling ball so hard that it didn't hit the wood till it was halfway down the lane. When he was coaching the junior team he told Ordie Jones that he had to quit either Boy Scouts or baseball. Ordie was a King's Scout and a terrific ballplayer. He quit the team.

The Dickytown alphabet

Boy, you got a good view up there in that box on the roof. Whenever anyone made a hotdog run, you could feel the roof swaying, and as the afternoon wore on the hot Okanagan sun blasted its way in. I was really glad when the outfield fence went up. It made my dicky little town (officially still a village then) seem a bit more like the professional leagues.

"What do you figure?" I asked my dad. "Is the Okanagan Mainline League sort of equivalent to Class B, or maybe Class C?"

"I think you have to learn a little more of the alphabet," he replied. He always said stuff like that. He's my role model, though I have never been patient enough to match his subtlety.

You have to understand that the sun is blazing down about 99 percent of the daytime hours in the South Okanagan. When those cars were parked in the outfield, pointed toward home plate, the reflected sun glare off the windshields made hitting a challenge, especially when Vern Cousins or Eddie Stefan was pitching. Often you would hear Cy Overton announce, "Would the owner of the blue Mercury in right field please move his car or cover the windshield!"

When the fence went up and local businesses bought ads on it, I thought oh boy, real home runs. Not triples with an extra ninety feet of dead-out running, but real over-the-fence home runs, like those the Cleveland Indians hit. The Washington Senators. Well. Okay. There would be about one over-the-fence home run every ten games, and it would be hit by some big U.S. import playing for Trail.

Just more proof that I lived in a dicky little town that couldn't do things the way they did them in real places, especially across the line. The putting "greens" at the local golf course were made of rolled sand mixed with oil. There was no radio station. There was something amateurish about the high school cafeteria. It just didn't have the confidence of the ones we saw in U.S. movies or in Archie comics.

But all things considered, I figured that our baseball was as close to real as anything in Oliver.

The Dooney's Café website has a repository of Bowering baseball memories written by Brian Fawcett and Jamie Reid and Stan Persky. Bowering's latest book of poetry, Vermeer's Light, will be published in October. ![]()