- Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling

- Random House Canada (2007)

Bret Hart's autobiography Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling reminded me of a completely different bestseller, Guns, Germs, and Steel, a book by Jared Diamond about the geo-politics of human history. No, really.

In Guns, Germs, and Steel, Diamond points out that despite having a significant technological edge on the rest of the world and despite having already possibly discovered America, China in the early 15th century did not colonize the globe. Europe did.

Why? Because China was taken over in the latter half of the 15th century by an anti-science and anti-exploration dynasty. And because the Chinese territory had few easily-defensible geographic barriers, that dynasty's political reach was pervasive and total. Thus, those who wanted to continue pursuing new ideas or exploring the world simply couldn't.

Europe, too, had its share of scientific intolerance. But it differed from China in that it had easily-defensible geographical obstacles (rivers, mountains, ocean channels, and so on). With these barriers come numerous autonomous political entities (monarchies, fiefdoms, and so on). With this political diversity comes the reality that ideas banned in one place might be allowed and supported in another.

So, for example, Christopher Columbus when denied support by one monarchy went to another and another until he found what he needed. Had Europe been united under one power, he likely never would have "discovered" America. While it's debatable whether that discovery was a good thing (just ask the Arawak Indians), the freedom to freely ply one's trade certainly is.

Thus, geography was the key to political diversity and political diversity gave people a certain amount of freedom.

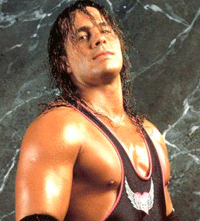

What does any of this have to do with the autobiography of Calgary's seven-time World Heavyweight Champion, the man in pink tights, greasy hair and wrap-around sunglasses, Bret "Hitman" Hart (said rolling-thunder style like a ringside announcer)? On the surface, nothing. The book is a compelling blow-by-blow account of back-breaking suplexes, flying elbows, and figure-four leg locks, not to mention the steroids, pain killers, and premature death that go with them.

But Diamond's theory shows itself in subtle relief against the subtext of Hart's career, a career that started in the era of the diverse, autonomously-owned wrestling territories and ended in the era of Vince McMahon's nationally-televised World Wrestling Entertainment monopoly. The rise of this empire was possible only when there were no more geographic obstacles.

Wrestling territories = political diversity

Look first at the wrestling world Hart was born into in the '70s. His father, Stu Hart, was a legendary wrestler who started the Stampede Wrestling promotion in Calgary. Some of the wrestlers he trained in his basement (and who eventually married into the Hart family) included The Dynamite Kid (now paralyzed), Davey-Boy Smith (now dead), and Jim "The Anvil" Neidhart. His Stampede Wrestling ran shows across western Canada as part of the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA).

The National Wrestling Alliance was founded as a loose federation of wrestling promotions that covered North America and included, among many others, Vancouver's All-Star Wrestling, Toronto's Maple Leaf Wrestling, and New York's Capitol Wrestling Corporation. According to Hart, promoters ran their own territories, selected their own champions, but also traded talent and recognized the NWA champion as the one true world champion. The NWA World Champion would visit all the territories and take on the top contenders in each. And, most importantly, "nobody ran in another man's backyard."

Wrestling 'zines as agents of 'kayfabe'

The only way wrestling fans could keep track of their favourite wrestlers as each hopped from territory to territory was through wrestling magazines. I was about 13 when a friend passed me Pro Wrestling Illustrated in the back row of Mr. Jones's social studies class. This was the early '80s. Although Vince McMahon's cartoon wrestling was getting more and more popular, wrestling still took itself seriously. Bad guys (heels) and good guys (babyfaces or faces) would never be seen in public together, even if they were the best of friends, even if they were related. It was a time of true kayfabe.

(Kayfabe is a word Hart uses a lot to describe these early days. It's a word that Wikipedia says is "thought to have originated as carny slang for 'protecting the secrets of the business.'" That secret, or course, was that wrestling -- while athletically demanding and dangerous -- was staged.)

While the poorly-lit amateur-ish antics on TV seemed pretty unconvincing, the magazines sucked me in with the back-stories that blurred the lines between the play and the reality, stories like that of the Von Erich family, who were the victims of some dark and unknowable wrestling curse, a curse that had (in reality) killed four of five wrestling sons and one non-wrestling son. The magazines (which I gullibly read as "insider" trade rags) gave me the gothic narrative that propped up the televised phoniness.

In other words, the magazines kept my wilful suspension of disbelief wilfully suspended for the same reason that Shakespeare kept most of his horror off-stage. Because it's only in the human imagination that staged horror can grow to truly monstrous proportions. But all that ended as wrestling became more and more a televised event.

He who owns television, owns the world

The rise of cable television in the '80s spelled the end of this territorial system and gave McMahon the advantage he needed to consolidate his power. According to Hart, "Suddenly, the local wrestling shows that served each market were popping up everywhere. Promoters who had got along on mutual respect and a handshake were now competing with one another, unintentionally, because their shows aired in whatever markets the cable systems happened to expand into."

The turning point came at the 35th National Wrestling Alliance convention in Las Vegas. "There were 60 of us in the room listening to a lot of boring speeches. . . . Everyone skirted around the issue until Ole Anderson got up and got right to the point, talking about how the New York territory ran its TV in his Ohio markets. Ole stared hard at Vince Jr., but Vince remained impassive. 'If you want war, McMahon, I'll give you war! I'll run in your Pennsylvania towns.'

"Everyone started arguing, and there were cries of order. Then Vince stood up in the midst of the commotion and simply walked out. In that moment, I was witness to the beginning of the end of promoters such as my dad and regional territories such as Stampede -- though none of us recognized that at the time."

In other words, by syndicating his wrestling shows across North America, McMahon generated more revenue. With that extra revenue, he started buying the best talent from each territory, talent like Hulk Hogan. Inevitably, each territory had no choice but to close or sell to McMahon, which is what happened to Stampede Wrestling. It was only a couple of years ago that the last holdout, Ted Turner's WCW, sold to the WWE.

Thus, cable television (along with earlier developments such as cross-country air travel) made it so that geography was no longer an issue in the North American wrestling landscape. As a result, one political/corporate entity was able to control a vast area. But, like China in the latter 15th century, that left people with few options. In other words, if wrestlers didn't have the option to go to other territories, they were at the mercy of the WWE and at risk of exploitation.

He who owns the world, can exploit it

Hart never explicitly characterized the treatment of the wrestler in the WWE as exploitive. In fact, he included a letter, somewhat maudlin but totally heartfelt, thanking McMahon for all he'd done for his career. Yet, he also doesn't mince his words about what it was like to spend one's life in this traveling athletic pantomime.

First, the steroids. Hart never says that McMahon forced wrestlers to take steroids. McMahon did, in fact, implement a drug-testing program in the midst of negative media exposure in the '90s. But Hart also points out that McMahon himself bought steroids and that he preferred wrestlers who look like they "spend a lot of time in the gym." So, it's probably also fair to say that the WWF created an environment where steroids were accepted, if not encouraged.

Besides, finding gym time must have been difficult for a wrestler who was kept on the road for close to 300 days a year, a schedule that, as Hart points out, was ironically called the "Killer Kalendar" by the company's marketing department. So, what's a wrestler to do when his livelihood depends on maintaining a massive physique but gym time is limited? And what's a wrestler to do when he isn't given the time between matches to let his body heal? Simple, steroids and painkillers washed down with a lot of booze.

"No one heeded the warning signs, though I tried really hard to be moderate. But the touring life forced you to alternate between running on empty . . . to running on adrenalin. Wrestlers used drugs and alcohol to mediate the highs and lows," Hart admits.

The wrestling world that Hart describes is a constantly-shifting house of mirrors controlled by a Machiavellian boss. In a world where everything is part of a potential story line and part of a ratings grab, how do you know who to trust? How do you know if the guy you're working with is going to catch you off the top ropes or let you fall awkwardly onto the concrete floor? Wrestling is a trade that requires trust but feeds off animosity. As wrestling writer Dave Meltzer wrote "Wrestling is more real and more phoney than people imagine."

Lessons learned

So, in the rise of the WWE not only is there a lesson about geography and empire (something we need to keep in mind in terms of the Security and Prosperity Partnership), but also one about worker exploitation. Perhaps, as Hart advocates, it's time for these big men and women who pretend to hurt each other to organize and unionize so that it all remains pretend. After all, all other large sports and entertainment industries have done so. If they don't, let's not be surprised when we hear about the next wrestler with a broken marriage, broken body or broken life. Trust me, it won't be kayfabe.