"I was conceived in Bombay...India, where my father was working as a gun runner for Remington."

It is late in the last century on a rainy day in January, and Frank Harper and I are travelling through Clayoquot Sound and through his personal history. Our journey started at Smiley's Bowling Alley in Ucluelet, on the far side of the "Junction" from Tofino, and continued with many sessions and locales thereafter.

I had made what seemed like a perfectly reasonable request of Frank: would he tell me his life story?

I was interested in Harper's story because, for me, it traces the outlines of Eden and our fall from grace. A journey that began in Ohio moved on to surfing in then-pristine La Jolla, California, and, as slowly as progress itself, worked its way up the coast. As a young boy, Harper would cross the L.A. River ("when it was still a river") and sneak into the back lot of Republic Movie Studios, where Roy Rogers once saved Frank and a friend from the police. In Watsonville, California, Harper was fired as a high school teacher for stomping on an American flag in front of a classroom of horrified students. "I was only trying to teach them the arbitrariness of symbols."

Harper came to Clayoquot Sound with his young family in late June of 1970. "I was a teacher at a factory-like university in Oregon, seeking to change my life, to find a way to drop out and to drop in: to find a simple place to live, to find community and self sufficiency and adventure, beginning at age 40."

In the process, he changed many lives -- and lost one very dear to him.

Tofino's own stories

Frank and I were neighbours of a sort. At the time of our Smiley's encounter, we lived across Calmus Passage from each other in Clayoquot Sound, he at Catface on Vancouver Island and myself on Vargas Island. Frank and a small group of friends continue to legally squat (and pay taxes) on a south-facing sandy beach on Crown land below the mountain that gives the place its name. Catface's bumpy outline can be seen from the Whiskey Dock of what he refers to as the "neo-classical resort" of Tofino.

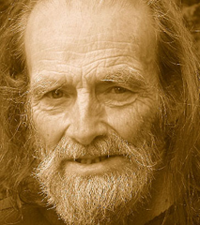

In the late '80s, when I came to Tofino, Frank was this elfin sage with a big beard and a twinkle in his sparkling blue eyes walking around town capturing stories for The Sound newspaper that he founded, edited and published with a village of volunteers.

Frank's talents include a great ear for dialogue and the ability to make you feel right there in the story with him. The Sound, which originated in 1990, is the best record of Tofino life when it was still a fishing village at the end of the road. Harper is Tofino's Steinbeck.

From Harper I learned that the stories of the locals of a village as written by them make a most compelling and often humorous read. I applied this lesson to The GIG -- The Gulf Islands Gazette -- which I owned and operated until recently.

Harper is also the author of several three-act plays, such as Dream Rovers (1988) and Cougar Annie! (1996), which were staged in Tofino's community theatre.

Journeys, a new book published by the independent Cherub Books (with much help both financial and digital from the community of Tofino), is a collection of Harper's essays that appeared under the same title in The Sound. A few additional stories were written specifically for this collection. The book is beautifully illustrated throughout with Joanna Streetly's line drawings.

Journeys is perfectly bookended by two stories set 30 years apart. Both find Harper struggling to get to the Whiskey Dock in his car. In the first tale, a dog sleeping in the middle of the road stops him; in the second, tourist traffic gridlock holds him up. Other stories include an amusing tale of a bogus tsunami warning, a canoe rescue from Catface, a storm journal, life as a wilderness chef cooking moose meat, our occasional beastly attitudes towards nature and, oh, a tale set in Smiley's Bowling Alley with a pesky interviewer.

Journeys is filled with true life adventures in which (as Harper notes in his foreword) "I'm usually the central character, but the book deals with a more profound journey than mine; an ever-changing mysterious wilderness is intruded upon by the sudden, money-haunted globalization of a tiny village."

Still, Harper neither decries nor laments; he simply uses his keen eye and ear to help us bear witness. What follows are excerpts from Journeys.

Sometimes I live in the wilderness...

"...or what some still call wilderness, and sometimes I live in the town, or what some call a high-end touring destination. My favourite, my real home, is the former, seven miles across the water from the municipality on a secluded beach in the old growth rainforest. When I journey to town by speedboat, successfully, it takes about 25 minutes, not counting loading and leaving the beach through surf. If I was to walk to town it'd take about two weeks, considering how rugged and fjorded the land is in Clayoquot Sound here on the outer coast of Vancouver Island.

"I built this real home many years ago, and added to it, a rambling hand-bopped, cedar-shake-and-board house with multi-paned windows and Plexiglas skylights, and sometimes still there are bears around, and martens and cougars and minks, eagles, deer, wolves and otters, but not so many anymore, no. The two ravens are still here, though. They must be 50 years old and still here even though during their waking hours, two hundred boats might zoom or chug past their nest.

"The town is named Tofino and it's contained by the peninsula it's built on, a formerly quaint and quiet fishing village, once the essence of nostalgia and simple living. Now more than a million people migrate through it every year. Now, with a newly heightened mystique hovering over Clayoquot Sound, there are whale-watchers and ecotourists, gift galleries and expensive restaurants, a plethora of come-on signs, condos, vacation rentals, and there's some aromatherapy."

The Sound

"The entire journey of The Sound began with my great-grandfather in a tiny town in Ohio where he was a newspaper editor and a wild-eyed rabble-rouser for change, according to a Civil Wartime news story I once read about him. My grandfather and my father, too, worked on newspapers most of their lives. So The Sound was pre-ordained: it came through genes.

"The paper also began with The Star, a one-issue, one-page tabloid I hand-printed when I was eight (there were only five copies, each one printed sloppier than the one proceeding), and I sold all five copies around the neighbourhood. (The number one story was sensational, about the mysterious massacre of six blackbirds whose bodies were left on a sidewalk.)

"When I was 13, I folded, biked and tossed 78 copies of the Los Angeles Herald express every day except Sunday, obediently. When I was 14, I hawked the San Diego Daily Journal on downtown street corners. ('Here-day-are-da-late-ones! Amelie-Earhat-Bones-Found on Pacific-Island! Allies-Advance-In-Normandy! Getch-ur-late-one!') My father was managing editor of this paper and later I was a copyboy there, carrying news stories to the composing room, dodging hot lead droppings and the linotypers' tobacco juice, moving the news along, feeling the energy of the news -- the events themselves -- vibrating into the editorial offices right through the teletype machines, right through the reporters' telephones: hardened, cynical reporters, many of whom cried at their desks when, in 1949, the Daily Journal shut down without warning.

"In college, I pursued journalism and practiced it in the then-rabble-rousing student newspaper, challenging the paralysis of McCarthyism as it kept appearing on campus in repressive, 1950s forms. But when I finished there, I must've graduated from journalism, from newspaper work. Because after college I had nothing except reading to do with newspapers for 34 years, 20 of which I spent mostly in the wilderness of Clayoquot Sound. Until 1990, when we started The Sound."

Celebrity wedding at Catface

"Two beautiful women cruised into the bay at Island Beach in a sturdy aluminum boat that soft summer day as I stood watching from the shade of an alder tree. The boat was being driven, carefully, by my friend Cristina Delano-Stephens. Her companion was the movie actress Barbara Williams from Los Angeles. They were advance location scouts so to speak, come to scope out the beach and the house for a wedding that was to take place here in the wilderness a few days hence. Barbara was to be the bride; Cristina was to do the catering. The groom, Tom Hayden, one of my political heroes in the 1960s, was at the anti-logging demonstration at Kennedy River Bridge that day. I helped Cristina anchor the boat and then we toured the set...

"Brown haired Barbara, when she arrived with Cristina, was wide-eyed with the beauty of the place. 'Oh!' she would exclaim, and 'Ah!' she would say, even though she told me she was born up the coast of Vancouver Island, somewhere in Nootka Sound, I believe. She was serious and concerned and open, was in love with Tom Hayden, and was quite involved in making wedding plans. There'd be a trio of strolling musicians from Tofino with flute, mandolin and guitar. Transportation was already arranged. There'd be two wedding officiators, a Buddhist priestess and an Indian shaman. There'd probably be about 25 guests and, yes, I could invite the people of the Catface community.

"I laughed. 'There's only one outhouse.' "

The longest journey

"The longest journey of my life was a short one, maybe a quarter of a mile, but I often make this same trip inside my head, again, again.

"In the middle of May in 1988, late on a rainy Sunday afternoon, my nine-year-old son Jesse disappeared from a hollow near a trail not far from the house on Island Beach where he was born. That afternoon we found only two signs. One was a large, fresh print of a cougar's foot -- just one, pressed into the brown, speckled sand -- on the next beach near a creek. The other was Jesse's orange rubber ball, tennis-size, in the woods, on the trail near where my son-in-law left him while on a walk. The ball on the ground I can still see clearly; throbbing against the wet green, looking so out of place; but whole, globelike, as if orbiting...

"I remember standing in front of my house, looking at already silver whitecaps and at the anchored coastguard lifeboat, and I can remember still, down through all these years, how Pappy's voice sounded from far back in the woods, barely audible like a heavy whisper, but strong, squeezing right through the wind, calling: 'Frank!...Frank!...I...found...him!' Then repeating until drowned out by the helicopter's pockpockpockpock, and that was when my longest journey began.

"I crossed the creek and forced my feet to climb the hill past the outhouse and forced them further, deep into the thickets of salal, careful now, methodical, one step at a time, this foot then this foot, making my own way, trying to analyze the meaning of Pap's words: did he find him alive? Purposely, I moved slowly because I didn't want to know what I already knew. (You know?) I stepped around ferns, felt my way around towering berry bushes, climbed over root systems, parted salal carefully, and all at once it felt as if Jesse himself was right there with me, as if the two of us were moving through the forest together as we had so many times before, but this time we were going to see if he was alive even though I knew, on that level of knowing for a certainty, that he was not anymore, no, just as the ball had told me that day before. Still, I wished Pap would yell again.

"Jesse and I moved even more slowly, over downed and rotting trees, through deep boggy pools of water, until I could hear human voices ahead, mutterings through the bush, mumblings, and then I -- we -- saw the heads and shoulders of a group of men and we entered a little grassy glade, poured with filtered sunlight, and Jesse left me there." ![]()