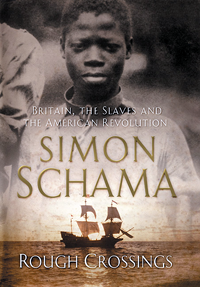

- Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution

- Viking (2004)

- Bookstore Finder

It's a shock to read a history that revises what had seemed carved in stone. The shock is doubled when the history throws new light on one's own book.

Simon Schama gave me such a shock in Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution. He forces us to look again at Canada's origins as well as the birth of the U.S.A. Even B.C.'s early history looks different in the light of Rough Crossings.

The winners write history, but this is an account of the losers: Britain and its loyalist supporters in the American Revolution. Schama makes us realize that the revolution was really the first American civil war. And like the second one, slavery (not tea taxes) was the critical issue.

The rebels who declared independence fought their loyalist neighbours as much as they fought British redcoats and mercenary Hessians. And without the wealth produced by black slaves, the white rebels would have lacked the resources to sustain a war.

The British understood the hypocrisy of liberty-loving patriots who enslaved their fellow men, and the patriots themselves were extremely thin-skinned and defensive about it. Schama quotes Patrick Henry, but it's not "Give me liberty or give me death." Henry understood how compromised he was as the owner of slaves. His only excuse: "I am drawn along by the general inconveniency of living without them."

The first emancipation

Slavery had been an issue in Britain also, and in 1772 a King's Court decision reverberated from London to the American colonies and eventually around the world to colonial Victoria, B.C. It is reverberating still.

James Somerset, a slave owned by Charles Stewart since 1749, had travelled with his master from the American colonies to London in 1769. Late in 1771, fearing he would be sold and shipped to the Caribbean, Somerset vanished -- but was soon found and kidnapped by professional slave-catchers.

This was routine in 1770s London, but in this case a witness secured a writ of habeas corpus. A test of slavery's legality in Britain followed, and the decision by Lord Chief Justice Mansfield established a radical principle: by simply setting foot on British soil, a slave became free.

When war broke out in the American colonies a few years later, the principle was applied in whatever territory the British controlled -- not to uphold the law, but to weaken the rebels economically. British authorities made it known that slaves who escaped their masters and came through the British lines would be automatically liberated. (This did not apply, however, to slaves belonging to loyalists.)

Ex-slaves could work for British pay as carpenters, cooks, laundresses and soldiers. And they did. The loss of slaves seriously compromised the rebel war effort. Even some of Washington's slaves defected. Meanwhile, black soldiers fought effectively for Britain in both set-piece battles and guerrilla campaigns.

The British actually suffered from the success of their policy -- so many blacks swarmed in that not enough work or shelter was available for them. Thousands died of smallpox and other diseases.

When the tide turned against the British, they had to remove not only their own troops but white and black loyalists. Many in both groups chose to move to Nova Scotia, where they were promised both land and tools.

Betrayal followed at once. Some blacks were left behind and re-enslaved. Those who migrated to Nova Scotia (and then to New Brunswick) received little or no land, and were soon forced to indenture themselves to white loyalists -- in effect, a new kind of slavery.

Another promised land

The anti-slavery movement in Britain was growing in force in the 1780s, and its leaders were aware of the plight of the Nova Scotian blacks. As a way of redeeming British promises, and also striking at the source of the slave trade, anti-slavery leaders developed a plan to settle the Nova Scotians in Sierra Leone. A democratic, productive community there could turn the whole continent away from slavery to the blessings of honest trade.

John Clarkson, a British naval lieutenant, was appointed to lead this new migration, and he succeeded brilliantly. He canvassed the black Nova Scotians, signed up hundreds, and commissioned a fleet of 15 ships to transport over a thousand migrants to Africa. It was an epic journey forgotten in North American history.

Once there, Clarkson and his people struggled against climate, disease and nearby slave-trading depots, but they established a thriving community complete with school and hospital. They elected a local government under Clarkson, and even some women had the right to vote.

But when Clarkson returned to Britain, life turned sour: other whites ran the settlement like a typical colony, treating the blacks with contempt. The Nova Scotians revolted, and were put down -- ironically, by a body of Maroons, Jamaican ex-slaves who were being resettled in Sierra Leone.

Echoes in British Columbia

I had known essentially none of this before reading Schama's book. I had a vague awareness that blacks had been among the resettled loyalists, and that Sierra Leone had been founded to repatriate ex-slaves.

I did know of the Somerset case, however, because it played a key role in the gold-rush history of British Columbia. While researching my book Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia, I learned that in 1860 a young black slave, Charles Mitchell, had stowed away on an American ship from Olympia, Washington territory, to Vancouver Island. Discovered, he had been locked up on the ship when it docked in Victoria. The captain planned to restore him to his owner on the ship's return.

Victoria's black community, recent émigrés from San Francisco, soon learned about this, and they too secured a writ of habeas corpus. The boy was removed from the ship and brought before a judge -- who invoked the Somerset case and ordered him freed.

Like the black loyalists, B.C.'s blacks were seeking a better land, following the promises of B.C. governor Sir James Douglas (himself part black). And the blacks of the gold-rush era also saw the promises eventually broken. Most returned to the U.S. after the Civil War, hoping that America would be better. That would be yet another disappointment.

The wealth of the British Empire in America was founded on slavery, and the revolution was just a quarrel about dividing the profits. But some Britons and Americans saw the injustice that created that wealth. They launched the first real campaign of social engineering. Within a few decades they had abolished slavery in the British Isles. They also created such a conflict in the U.S. that (at a terrible cost) Americans eventually abolished slavery there as well.

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation was essentially a repeat of the British political tactic four score and seven years before. While it was a flawed document, and led to yet more broken promises, it helped prepare the way for future generations to achieve something closer to the vision of John Clarkson -- a society of equal blacks and whites, working in harmony. We have more rough crossings to make, but we are getting there.

Crawford Kilian is a frequent contributor to The Tyee. ![]()