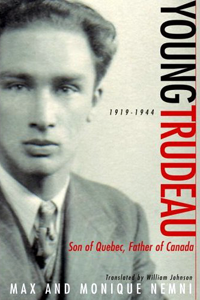

- Young Trudeau: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada, 1919-1944

- Douglas Gibson Books (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

To younger Canadians, Pierre Elliott Trudeau is a historical figure. He may haunt their parents and grandparents, but they accept (and take for granted) the Canada he built for them.

Even we elders take Trudeau's Canada for granted: a multicultural federal state under a Charter of Rights whose implications we are still coming to terms with. But a new book demonstrates that the man who made us what we are today was an unlikely architect of such a nation.

Young Trudeau: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada, 1919-1944 is a remarkable intellectual history of Trudeau's education and the insular Quebec he grew up in. It obliges us reconsider not only his roots but also those of modern Quebec nationalism.

The authors, Max and Monique Nemni, had Trudeau's permission to research his early papers -- and as a student he had been a prolific writer. What they found in those papers was the education of a fascist.

The church and the 'corporatist' state

I do not use the word lightly. But the Nemnis show us that the Quebec of the 1920s and 30s was xenophobic, anti-Semitic and locked into submission to a rather backward outpost of the Catholic Church. Education was a key task of that church.

Trudeau, born into wealth, was educated in a Jesuit-run classical college. He accepted the church's politics as well as its morality. And in the Quebec of Trudeau's youth, the church believed the successful nations were the "corporatist" states: Mussolini's Italy, Hitler's Germany, Franco's Spain and Salazar's Portugal.

These models were especially attractive as the Depression staggered the industrial world. They appeared to offer stability and work, and usually rule, by a church-inspired elite. This was attractive to French Canadians, and especially to the church-educated children of the elite.

When the Second World War broke out, Quebec's intelligentsia saw it as just another European quarrel, and nothing to do with them. The defeat of France was a proof in Quebec that secular democracy had failed; Vichy France under Marshal Petain was a vindication of the corporate state.

Hence the hostility to fighting the Nazis, and especially to fighting them with conscripts from Quebec. Church and intelligentsia alike took anti-fascist news reports as so much British and Anglo-Canadian propaganda.

Trudeau studies the coup

Through the Depression and the early years of the war, Trudeau was receiving a superb classical education, and thriving on a curriculum far more rigorous than any offered today. He read voraciously in French literature and Catholic philosophy, with forays into English and other European literatures. He took copious notes on every book he read, and exchanged letters about them with his classmates. (He also wrote anti-Semitic plays, performed in school with great success.) When he needed to read books prohibited by the church, he always asked for permission first.

But he was not the pampered, apolitical playboy we were told he'd been. Yes, he rode his Harley Davidson wearing a Prussian helmet -- but apart from such pranks, he was engaged in a deep and systematic study of how to launch a coup and run a revolution in Quebec.

This phase of his life is still obscure, but the Nemnis show that in 1942, when he was 23, Pierre Trudeau was a leading organizer of a revolutionary cell called "LX," whose purpose was to conduct a coup leading to a corporatist, independent Catholic and French Quebec. Catholic educators and writers had inspired these young revolutionaries, and at least one Jesuit appears to have been among the organizers.

"Impale traitors alive"

Judging from an anti-conscription speech that Trudeau gave in 1942 (supporting the young Jean Drapeau in an Outremont by-election), his would not have been a velvet revolution. Speaking to thousands at a rally, Trudeau said that government "traitors" should be "impaled alive."

And he urged his listeners that "if Outremont is so infamous that it elects La Fleche, and if because of Outremont conscription for overseas service comes into effect, I beg of you to eviscerate all the damned bourgeois of Outremont."

So Trudeau himself, as a young man, would not accept the democratic wishes of his fellow citizens. The only true French-Canadians were those who thought as he did, and any who disagreed could not be legitimate representatives. Had the anglos and Jews of Outremont voted for Drapeau, that was OK; when they voted instead for La Fleche, as they did, they were outsiders deserving only death. Democracy in any case would not survive Trudeau's coup.

Until the war was near its end, Pierre Trudeau appeared set on a course for oblivion. He had flourished in an airtight intellectual climate, sealed off from all but approved authorities. Far from challenging them, he had accepted them and pursued their ideas into a blind alley. If he had continued, he might have ended up in jail, or the Quebec equivalent of Doug Christie, defending francophone fascists and anti-Semites (and maybe the FLQ). He would have been, at most, a footnote in our history.

Escape from a blind alley

Instead, domestic and foreign events and his own intelligence appear to have pushed him out of the blind alley. Quebec nationalist politics in 1943 and 1944 were bitter and fractious, and the LX group evaporated. The collapse of fascism, and the growing revelations about life under the Nazis, discredited the Jesuits' fantasies.

The very traits and training that had made Trudeau such a good student were now to rescue him. His Jesuit education led him to see the follies of Jesuit politics. He continued to read right-wing thinkers, but more critically. Under a corporatist professor he had read Adam Smith without effect; reading Smith on his own, Trudeau understood far more.

He would go on to study at Harvard and to break decisively with a religious, ethnocentric vision of politics. He still saw himself as a statesman in training. But it would be a very different kind of state that he would build and serve.

Meanwhile, narrow Quebec nationalism would remain in the blind alley Trudeau had escaped: now more secular than religious, more left-wing than right, but still nursing grievances and resenting outsiders -- "money and the ethnic vote," as Jacques Parizeau in 1995 echoed the bigots of the 1930s.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau, once a privileged and bigoted insider, understood Quebec's nationalists better than they understood themselves. Thanks to this book, we too begin to understand.

Crawford Kilian is a frequent contributor to The Tyee. He still has the copy of Federalism and the French Canadians that he bought in 1968. ![]()