- Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor

- University of California Press (2004)

- Bookstore Finder

If the media focus of the World AIDS Conference, which wrapped up last week in Toronto, must be on the notable white men in attendance, there is at least one person worthy of knocking Bill Clinton, Bill Gates and even Canada's Stephen Lewis out of the spotlight. His name is Dr. Paul Farmer. I don't believe he has ever appeared on Oprah, so you can be forgiven if you've never heard the name.

Dr. Farmer did manage to make the news last week in Toronto, though not the front pages, by making the simple point that food is a prerequisite for treating AIDS. "We don't know how to treat this advanced disease without food," he said, adding that many of the drugs need to be taken on a full stomach or with a meal. The correlation between severe income inequality and AIDS infection rates is but one of the themes that Farmer has been highlighting for years.

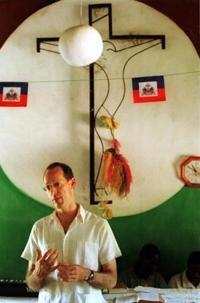

For two decades, Farmer has blazed an exemplary trail, combining the high ideals of equality and justice with remarkable practical work in delivering health care to those most in need, primarily in rural Haiti. The NGO he helped to found, Partners in Health, has mushroomed into an international operation, combating the scourge of HIV-AIDS and the resurgence of tuberculosis in places as far flung as Chiapas and Siberia. But Haiti has been his base, the place where he has applied the principles of liberation theology, and its notions of acting from the perspective of and advocating for the poor, to medical practice. Farmer, a medical anthropologist, infectious-disease specialist and professor at Harvard, has also produced an impressive body of written work, bluntly identifying structural violence and rampant inequality as the ultimate social and economic diseases afflicting today's world.

Our wealth, their poverty

His 2005 book Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor sets down, in no uncertain terms, Farmer's philosophy on the connection between economic interests and health care provision on a global scale:

"Arguments against treating HIV disease in precisely those areas in which it exacts its greatest toll warn us that misguided notions of cost-effectiveness have already trumped equity.... To argue that human rights abuses in Haiti, Guatemala or Rwanda are unrelated to our own surfeit in the rich world requires that we erase history and turn a blind eye to the pathologies of power that transcend all borders."

This book -- an all-too-rare analysis that combines anthropological, medical and historical insights -- is informed by Farmer's own experience, often using specific cases to drive home the point. He describes in horrific detail, for instance, the murder of one Chouchou Louis by the military regime in Haiti that presided after Jean-Bertrand Aristide was first overthrown in 1991. Louis died after three days of catastrophic bleeding into his lungs, caused by a gang of soldiers' arbitrary, vicious beating and torture.

In Haiti, and especially in its rural regions, where the majority of the impoverished population resides, death arrives as often in less overtly violent but no less unjust ways. Over the past 20 years, Farmer has helped to carve out an oasis of sorts with his free clinic in the village of Cange. The fortunes of Zanmi Lasante's (Creole for "partners in health") home base have ebbed and flowed with the struggle for democracy in Haiti.

The bay of AIDS

During the bloody military rule that followed the 1991 coup, Farmer took a 10-day hiatus in Quebec city to draft a sweeping indictment of U.S. policy towards Haiti. The result was The Uses of Haiti (Common Courage Press, 1994, updated in 2005), which begins its exposition of U.S. hypocrisy and human rights violations in a setting familiar to critics of the more recent "war on terror": Guantanamo Bay.

Gitmo, it turns out, served from 1991-93 as a "concentration camp" for Haitian refugees who were HIV-positive, according to the testimony of those detained. Like those held at Guantanamo today, the Haitian victims were severely abused; they staged long hunger strikes to protest their conditions and some, in despair, attempted to commit suicide. Of course, the story of the Haitian refugees was largely ignored in the U.S. This is just one example of how each successive crisis in Haiti, such as the second coup against Aristide in 2004, seems to be treated independent of any historical context. Noam Chomsky contributes the introduction to The Uses of Haiti, grimly stating at the outset, "This is a book that I fear is fated for oblivion" due to its challenge to orthodox assumptions about U.S. policy.

Paul Farmer's work, both intellectual and medical, seems destined for a somewhat better fate than Chomsky predicted.

'God loves the poor more'

One reason is an accessible and, well, gushing biography by journalist Tracy Kidder. Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a Man Who Would Cure the World (Random House, 2003) tells the story of Partners in Health and its dynamic founder in page-turning, inspirational prose. We find Farmer expounding on the idiocy of post-modernism while hiking in the Haitian backcountry to make house calls; cajoling the conservative medical establishment into action on AIDS treatment for the poor at glitzy international conferences; holding forth on the virtues of Cuba's selfless and dedicated doctors while he and his biographer wait for a flight out of Havana; and making the case for the application of the principles of liberation theology to health care to any and all who will listen.

Farmer's attraction to this intellectual tradition of struggling to create "heaven on Earth" -- influential in numerous Latin American social movements and espoused by Hugo Chavez and Aristide among others -- came from reading but also from listening to the poor peasants of Haiti. He relates to Kidder that it was, he thought, as if these people were saying to him, "Everyone else hates us, but God loves the poor more. And our cause is just." The most attractive feature of liberation theology to Farmer was its constant call to action, its incessant interrogation: how are one's actions serving the poor?

Kidder reveals that Farmer also holds a number of avowed atheists among his heroes, dangerously leaving his books about Ernesto "Che" Guevara strewn about his office in Cange even in the years of harsh military repression. The Argentine-born Guevara, like Farmer, was a medical doctor whose thirst for social justice took him on travels far from home. Che, of course, traded his medical kit for the guerrilla's rifle and ammunition belt. Farmer's tactics differ. He won't likely have his image used to sell t-shirts or appear on the TV talk show circuit. But he seems just as determined to spread his revolution -- the human right to health care -- and he has already changed the world for the better.

Derrick O'Keefe is a founder of the online journal Seven Oaks.

Related links and Tyee stories: For the Partners for Health web site click here. For a lecture given by Farmer last year at Calvin College, in Grand Rapids, MI, click here. For the first part of a Tyee series on the connections between Canada, Africa, AIDS and poverty, click here. For an excerpt from Kidder's Mountains Beyond Mountains, click here. For an excerpt from Farmer's Pathologies of Power, click here. ![]()