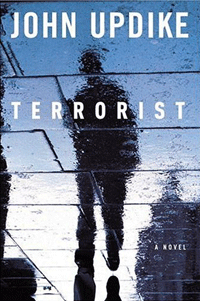

- Terrorist

- Knopf (2005)

- Buy this Book

Karl Marx said of peasants: "They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented." Roughly 125 years later, Edward Said began his labyrinthine magnum opus, 1977's Orientalism, with that pithy condescension toward the peasantry. Said ostensibly used it to highlight the western intellectual's habit of speaking on behalf of exotic folks from the Muslim East (not that I would presume, of course, to tell you what Said was thinking).

Yet westerners persist in telling each other what the Other is thinking: Raphael Patai's The Arab Mind (1976, revised in 1983); Bernard Lewis's The Multiple Identities of the Middle East (1998). The West makes noises about how it accepts the notion that every people has a right to tell its own stories, but -- as the attention and praise now being lavished on John Updike's Terrorist shows -- western audiences are captive to a lethal paradox.

They are obsessed with what Muslims think, why they're so angry, and what makes them (and their carry-on luggage) tick. But the very nature of this obsession, and its basis in paralyzing fear, leads them to distrust and discount narratives from Muslim sources.

Voices from predominantly Islamic parts of the world tend, after all, towards the simplest possible explanations for Muslim frustration -- rather than Ockham's Razor, call it Hakim's Razor: the U.S. military presence in Saudi Arabia; western support for Israel's increasingly brutal and humiliating occupation of Palestinian territories; the terrors visited upon the people of Iraq; the propping up of thugs and despots from Indonesia through Pakistan to Egypt.

Simple truths just won't do

But the West craves a more complex, psychosexual explanation for the seething discontent amongst the Muslims, one based on the envy of freedoms, the distaste for personal liberty and the paranoid jealousy felt by practitioners of a religion unready for science, progress, modernity or bathing suits.

So it's not surprising that a major American publisher is receiving massive amounts of attention for publishing a fictional speculation on the motives and beliefs of a devout Arab-American teenager caught up in a terrorist plot. And who better to tell the story of a teenage boy negotiating the world around him through the lens of Islamic faith while growing up in 21st century working class New Jersey than John Updike, a white man born in Pennsylvania in 1933? Surely, his experience on staff at the New Yorker from 1955 to 1957 must have helped Updike immensely in telling the story of Ahmad, a truck-driving, half-Egyptian high school track star in a post-9/11 world.

In constructing Ahmad's story, Updike does his best to work the angles to his advantage. Ahmad's Egyptian father is a deadbeat, having disappeared when Ahmad was three years old, and leaving the boy to be raised by his Irish-American mother. This relieves the author of the task of showing us what it means to grow up with Islam as the organic foundation of a moral existence; instead, Ahmad picks up the religion at age 11, in an act of precocious adolescent identity construction. (The image of the insolent adolescent is a recurring one in Western representations of Islam more generally.)

Like J.D. Salinger's protagonist before him, young Ahmad is mired in a solipsistic righteousness in relation to which everybody else falls short. Would that the tacit invocations of Holden Caulfield were the only reminiscences of John Guare's Six Degrees of Separation, but no -- Ahmad is separated by only four measly degrees from the head of the Department of Homeland Security, and this unlikely "Small World" connectivity figures centrally in the movement of the novel's plot.

First 9/11, then this?

Though he makes certain mistakes laughable to anyone with a rudimentary working knowledge of Islam -- devout Ahmad, for instance, has a "dog-eared copy of the Qur'an" (page 108), when to deface the Qur'an or to treat it carelessly is a blasphemy -- Updike has clearly done a lot of research. But like many people proud of new knowledge, he uses it decorously rather than substantially; Updike's frequent forays into Islamic imagery are hand-held excursions for non-Islamic readers, and as such Ahmad's tutelage under his imam, Shaikh Rashid, reads like Catcher in the Rye crossed with Islam for Dummies.

Perhaps because of the uncertainty that lies at heart of this novel -- a trepidation borne out by Updike's possible sense that he was not the person to tell this story -- the whole thing is shaky. Nearly every metaphor in the book is spelled out; because of the author's didactic posture (Updike is teaching you why Muslims are mad) he doesn't want to leave anything to chance. The characters that inhabit Ahmad's world are uniformly caricatures: secular Jews are over-thinking and libidinous; African-American men are violent pimps with ridiculous names (specifically, in this case, "Tylenol Jones"); women are either pathetic spinsters, obese and sexless food-obsessed cartoons, intellectually inconsequential sluts or sex workers.

Not even Updike's celebrated prose works this time around. Witness the following disastrous passage, wherein the aforementioned spinster lusts after her married boss at the Department of Homeland security: "She longs to comfort the Secretary, to press her lean body like a poultice upon his ache of overwhelming responsibility; she wants to take his meaty weight, which strains against his de rigueur black suit, upon her bony frame, and cradle him on her pelvis" (page 260).

First 9/11, and then that sentence? Hasn't America suffered enough?

Arguably the worst part of Terrorist, though, is that it is likely the failed product of good intentions. Updike's brilliantly scathing essay excoriating the notoriously anti-Muslim French author Michel Houellebecq in the May 22 issue of the New Yorker was so thoughtful and humane that it's hard to imagine the author put together this disaster of a novel out of enmity towards Islam; he was likely striving to build understanding, which makes it all the more tragic.

Exasperated Muslims may look at the attention that Updike's work is receiving compared to their own exhortations for understanding, throw their hands above their heads and cry "Ya salaam!" But the key phrase, I think, is to be found in another language with a debt to Islamic civilization, Spanish -- Ya basta. Enough already.

Charles Demers is a regular contributor to Tyee Books. ![]()