There are more than 120 tailings dams across British Columbia today, holding back a century of toxic mining detritus. Unless this number can be reduced, an average of two B.C. dams are predicted to fail in each coming decade.

The way to avoid this was laid out clearly in the wake of the Mount Polley mine disaster. For taxpayers and the environment to be protected, an independent review panel of three geotechnical experts concluded B.C. must move to safer ways of processing and storing tailings — the chemical and metal-rich byproducts of mineral processing.

Rejecting the notion that “business as usual can continue,” the review panel was clear that economic considerations must not trump long-term safety concerns.

But even after multiple investigations and dozens of recommendations adopted by the B.C. government, there are indications that business as usual continues.

Despite calls for the best available technology to be used at new mines, at least three planned big open pit metal mines propose to use the same wet tailings approach used at Mount Polley.

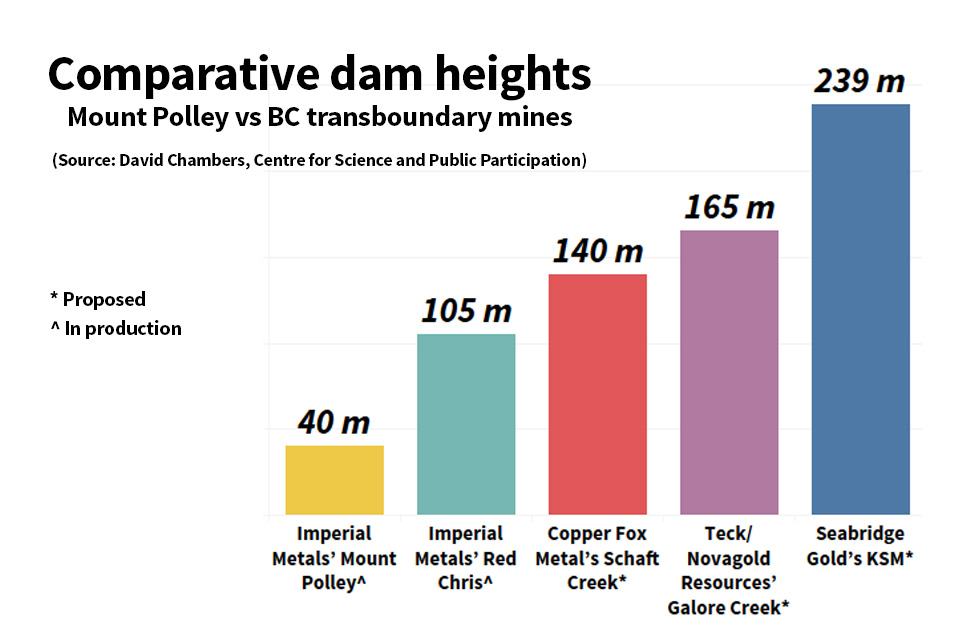

These northwest mines are more vulnerable to acid rock drainage (pollution that can occur when disturbed rocks are exposed to air and moisture) than Mount Polley. And the proposed tailing ponds are much larger, with dams up to six times as high and reservoirs holding 30 times as much water and waste.

All of which prompts the question: almost three years after the August 2014 Mount Polley disaster, what has changed to prevent B.C.’s next big dam disaster?

Back to business

The Mount Polley tailings spill sent the share price of its owner, Vancouver-based Imperial Metals, plunging from about $17 to $9 in a month. Today it’s about $6.

The mine didn’t stay closed for long though. The provincial government allowed the company to return to limited production less than a year after the spill.

Last June 23, the government authorized the mine to return to normal operations and process up to 20,000 tonnes of rock per day while continuing to store wet tailings. To date, Imperial Metals has never been forced to pay any fines for the disaster.

And just six months after the disaster, Imperial Metals’ Red Chris mine went into production using the same wet tailings design as Mount Polley. It’s the model B.C. mines have used for the last century, creating something akin to giant lakes by dumping a slurry of water, crushed metal-rich rocks and chemicals and holding it all in place behind dams.

The largest Imperial Metals shareholder (at almost 40 per cent) is oilsands billionaire and Calgary Flames co-owner Murray Edwards, a BC Liberal supporter who organized a $1-million Calgary fundraising dinner for Christy Clark’s 2013 re-election campaign.

Red Chris went ahead after Edwards helped arrange $150 million in loans — guaranteeing half the amount — and BC Hydro paid most of the costs for the $746-million Northwest Transmission Line into the region.

David Chambers, founder and president of Montana’s Center for Science in Public Participation, says the B.C. government has required Imperial Metals to pay just $12 million for a closure surety — a fund to pay for the mine closing, including reshaping waste rock piles, dismantling buildings and seeding the face of the dam. He estimates the real cost will be $30 to 50 million.

“So basically we have the B.C. government saying that a tailings dam that has the same design that failed at Mount Polley, run by the same company, should get a closure surety discount,” says Chambers, who has 40 years of experience in mine development. “There’s something about that whole piece of logic that doesn’t smell right to me.”

Imperial Metals did not respond to an interview request from The Tyee.

A spokesman for the Ministry of Energy and Mines says the province has addressed all the review panel recommendations and most of the recommendations from reviews by the Chief Inspector of Mines and B.C. auditor general.

Major changes include:

- Requiring mines to establish independent tailings review boards;

- New requirements from the BC Environmental Assessment Office for information to allow tailings management evaluation for proposed major mines;

- Updates to the tailings section of the province’s Mining Code; which include new design and operations criteria requiring water balance and water management plans for tailings storage facilities;

- Mines must now submit publicly available annual reports to the Chief Inspector of Mines, including details of reviews conducted by the independent panels and conditions that may compromise tailings facility integrity;

- A new website with links to mine information and ministry permits.

Towards a judicial inquiry?

In spite of all the inquiries and recommendations after Mount Polley, Calvin Sandborn, legal director at the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre, maintains that the provincial mine regulatory system remains “in a state of profound dysfunction.”

In early March, the centre released a report calling for a public inquiry based largely on what the ELC considers the government’s inaction (or watering down) of the most important recommendations from both the review panel and B.C.’s auditor general.

The problems, reports the ELC, are myriad. While the government now requires independent expert panels to advise owners (and regulators) on whether tailings storage facilities at new mines are “designed, constructed and operated appropriately, safely and effectively,” this advice is non-binding. The company is under no legal obligation to act on it.

There is also tension between safety and cost considerations. In the guidance document that accompanied B.C.’s new Mining Code, economics is listed as one of three factors that must guide assessments for tailings plans (the others being environment and society). The same document says constraints must be fully stated and considered, including “economics and financial feasibility.”

“The [panel report] is very clear in saying that safety has to be first, and I challenge anyone to argue... that that is the case today,” says Chambers. “Cost is the driving factor in building tailings dams, and if you don’t believe me, just look at how they are being designed in B.C.”

Province rejects AG’s overall recommendation

A public inquiry would also respond to the auditor general’s finding last May that B.C.’s Ministry of Energy and Mines is so close to the mining industry, it is “at high risk of regulatory capture.”

“Regulatory capture is when an agency is not single-mindedly serving the public interest,” says Sandborn. “It’s when they are serving, to some extent, the interests of the companies being regulated.”

The auditor general recommended moving the enforcement and compliance function out of the ministry. That would address the conflict in it being responsible for both regulating and promoting the mining industry. The B.C. government rejected the recommendation, citing a lack of evidence of regulatory capture.

Sandborn says that’s one of the reasons an independent review is needed.

“We have called for a public inquiry because current government regulation has lost public confidence,” he says. “No reasonable person can look at the Mount Polley mine disaster and the auditor general’s scathing report and conclude that the system works. The regulatory system is clearly bankrupt and must be fixed.”

A ministry spokesman challenged the idea that an inquiry is needed. He pointed to new funding to improve permitting processes and enforcement, including $18 million over three years for mine permitting and oversight announced in this year’s budget.

Amendments to the Mines Act last year allow courts to hand out tougher penalties to companies that break the law, increasing maximum fines from $100,000 to $1 million and possible jail terms from one to three years.

Just as this story was going to press, Energy and Mines Minister Bill Bennett rejected the call for an inquiry in a letter to the ELC, calling such a process “redundant.”

Welcome to the wild northwest

A mining company has many alternatives in dealing with tailings. Storing wet tailings — the approach used at Mount Polley — involves sending the waste slurry into a pond and letting it settle. Another option is to dry the tailings, removing about 25 per cent of the water, until the waste is the consistency of toothpaste.

Dry tailing storage is the optimal solution. It entails removing about 85 per cent of the water, which allows the waste to be compacted with a roller and stored without a dam or pond. It is also the most expensive option — in the short term at least.

Chambers says the full range of alternatives isn’t being considered in B.C.’s northwest corner.

There are at least three big proposed open pit mines in the region (as well as Red Chris which commenced production in February 2015), designed to tap very low-grade copper and gold resources, which in turn require the miners to sift through massive quantities of rock, generating much more tailings that the relatively small Mount Polley mine and necessitating much higher tailings dams to hold them.

Seabridge Gold’s KSM project has already received approval from both the provincial and federal governments to build one of the world’s biggest open pit gold mines not far southwest of Red Chris. The mine’s tailings facility (with a capacity of 2.3 billion tonnes) and rock dumps will ultimately drain into the salmon-rich Nass and Unuk watersheds of B.C. and Alaska respectively.

An independent panel that convened to provide advice on the best available technology for tailings at KSM confirmed that a wet tailings design was the preferable course.

Filtered tailings were “not a feasible option,” reported UBC tailings expert Dirk Van Zyl, who reviewed the report, due to “higher production rates” and site climatic conditions. (Van Zyl did not respond to calls seeking an interview).

The conclusion has left Chambers frustrated. He says the tailings dam design at KSM could employ drains to remove some of the water from the tailings, which would make the waste safer to store over the long term. He adds that the additional costs of treating the drained water would not be significantly more than what the company already must commit to treat water. But wet tailings it will be, if the mine ever goes into production.

It’s the same for every mine proposed for the trans-boundary region between Alaska and B.C., says Chambers. “So nothing has really changed, and to me that represents business as usual.” ![]()

Read more: BC Election 2017, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: