- The Underachiever's Manifesto

- Chronicle Books (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

"Look at all the nice things money can buy/Every day there's more and more/Do you ever stop to wonder why/You have to lock your door?" —The Rutles, "Eine Kleine Middle Klasse Musik"

It's easy for Rutle Neil Innes to reject the Protestant work ethic, because musicians are naturally lazy. (What do you call a drummer who splits up with his girlfriend? Homeless! Ba-da-bump.) Most people, however, need some guidance in finding their inner slug-a-bed.

I was set on my career in idleness by Edward Gibbon's The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. It was not the subject matter that affected me so much as the fine print, and thin-paper massive thickness of it all. When I began The Decline and Fall I was a bouncy, energetic, apple-cheeked youth, and by the time I was finished I was a gouty geezer in a tasselled fez, feet up on an ottoman, with a decanter of sherry on one side of my club chair and a stogie smouldering on the other. If you wish to experience life at a leisurely pace, Gibbon is your man.

But who has the time for 18th century historians anymore? In the new millennium, the demand is, "Quick, I'm on a schedule, tell me right now how to live more slowly." That demand must be there, because there are people willing to fill it.

First off the mark was Ernie J. Zelinski with The Lazy Person's Guide to Happiness (Vision International Publishing, 2001). Don't let its 158 pages intimidate you. On each one there is a maximum of half a dozen pithy statements, sometimes only one.

Buddhism and the stoicism of Marcus Aurelius are among the influences, though Zelinski complements his adages with quotes from sources as disparate as Horace, Abraham Lincoln, and Katharine Hepburn, and his own stuff occasional slips into a sort of slap-happy optimistic humour. ("Avoid falling in love with four members of the opposite sex all at the same time.")

I like much of his advice, such as, "Answer this important question: How many people do you know who on their death beds stated, 'I wish I would have worked more'?" Also likeable is that Zelinski does not get carried away with his own serenity. "To create more time for enjoying that mysterious and unpredictable phenomenon called life, minimize your search for the secret of it. Wiser people than you and me have tried without much success."

Improvable, but what's the point?

Less Zen but just as wacky, The Underachiever's Manifesto (Chronicle Books, 2006) is Ray Bennett, M.D.'s "guide to accomplishing little and feeling great." Found among his "not too bad" Ten Principles of Underachievement -- "Not great, but not bad," he further qualifies -- is a nice summation of his central thesis.

Under number seven, "Perfect is the enemy of good," Bennett tells us that "to seek perfection is to be cursed to find fault in the perfectly adequate, enjoyable, or even just plain good...With perfection in mind, it's frighteningly easy and almost inevitable to push things past good to the neurotically overworked, the belaboured, and the endlessly second-guessed." So, as Bennett says, turn it down a notch.

The satire of the self-help publishing industry is done with a light touch, and there is some excellent common sense, such as pointing out the frustrating fallacy that your one and only true love exists out there among six billion people. "If you accept this terrifying and deeply depressing notion, you must also accept that you have better odds -- much, much, better odds -- of winning the longest-odds lottery than finding Him or Her."

Bennett ends with a quiz that peters out after two questions, because if you care what your score is, you've already flunked. It might have been a better book if he'd put more effort into it, but what would the point of that been?

How much work do you want?

The above books originated in Edmonton and Seattle, respectively, and we also have a Vancouver appeal to the indolence in us all. Workers of the World Relax (self-published, 2006) is a manifesto of sorts for the Work Less Party, explaining how a planned-for shrinking of the economy would result in easier work for everyone, and less of it, too.

As a onetime federal candidate for the Parti Rhinoceros, I can appreciate how a fringe political party can raise significant debate about otherwise ignored issues, and even the political process itself, without seriously expecting support or seriously doing anything else, either. Schmidt's book, unfortunately, is very serious indeed.

Near the beginning of his tirade against consumerism, South African diamond mines, pulp mills, cows, and a host of other evils, Schmidt informs us that we require a fundamental redefinition of work. To better understand his economics, we should think of playing soccer, making our breakfast, or having a relationship as all being included under the heading of work. Sounds like a lot of work.

I can assure you it is, as getting through Work Less Party coordinator Schmidt's turgid analyses was the hardest toil I have accomplished in a while. Not nearly as snappy as Zelinski or Bennett, Schmidt also lacks the time-stopping weightiness of Gibbon. Reading Workers of the World Relax is practically guaranteed to prevent you from relaxing.

It reminded me of a time when I wrote an article about simplifying one's life, which is vague to me now except for the memory that I included at least one rule: Never own anything worth stealing.

After the article appeared, I got an e-mail from some people who were organizing a group to practise and promote simpler lifestyles and who wanted to know if I was interested. I came up with another rule: Don't try to simplify your life by forming a committee.

If you need rules to keep you in bed and away from heavy machinery, I can recommend the first two books, but not the third. Never listen to people who stridently tell you to take it easy.

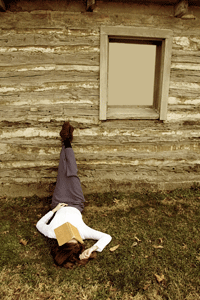

Verne McDonald hasn't bothered to write for The Tyee until now. ![]()