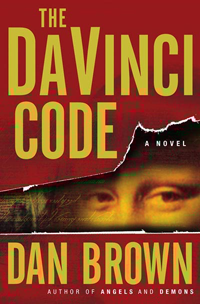

- The Da Vinci Code

- (2004)

- Bookstore Finder

A funny thing happened on the way to the theatrical release of the film adaptation of author Dan Brown's Da Vinci Code, that coked-out marketing orgy putting the 'circus' back in panum et circences. A prestigious panel of literary figures -- including Nadine Gordimer, Studs Terkel, Wole Soyinka, Don Dellilo, Julian Barnes, Alice Hoffman and many others -- responded to the New York Times's Book Review call for them to name the best work of American fiction of the past 25 years, and they chose, "solidly ahead of the rest" (according to the accompanying essay by Times critic A.O. Scott) Toni Morrison's novel of slavery and emancipation, Beloved.

Scott goes on to highlight the ways in which Morrison changed the landscape of the American literary canon, having "enter[ed], as a living black woman, the company of dead white males like Faulkner, Melville, Hawthorne and Twain." The rest of the top five featured the works of similarly revolutionary authors such as Philip Roth and Don Dellilo, white ethnic writers once very controversial in terms of subject matter and aesthetics respectively.

So what does this have to do with the Da Vinci Code? Well, keep in mind that, having been born in 1980, I'm of that post-Warhol, post-Sontag generation supposedly incapable of distinguishing between high and low culture. I went to school with guys writing theses on David Bowie, and I myself wrote an essay, for an upper division course in Marxist theory, all about Batman.

I'd be willing to bet that the vast majority of us saw the fractured and parodied component scenes of Citizen Kane on the Simpsons (some Simpsons' creators have bragged that they've done nearly every one) long before we'd ever seen the film itself. My generation so abhors canons, you'd think we were shell-shocked. And that pop culture populism is part of why people my age are so willing to shell out for Da Vinci and Harry Potter without the slightest guilt. Small wonder, when grown men and women are unashamedly reading children's books in public, that our generation has had both a hit band and hit TV series each called Arrested Development.

The levelling tendency to obliterate the Canon was once a very noble, very necessary one. As Scott implies in his depiction of Morrison above, the Canon was restricted to those with, to use Edward Said's phrase, "permission to narrate." The contradistinction between High and Low was toxically raced, classed and gendered. 'Craft' was substituted for 'Art' when women were preponderant in a given form; jazz lacked the seriousness of orchestral, classical European symphonies. Other writers have examined the celebration of George Lucas's American Graffiti in relation to the vastly superior Coolie High. The list goes on indefinitely.

We share what we're sold

Then somewhere, along the way, we started reading Dan Brown and J.K. Rowling. I can't count the number of times I've been called an elitist for suggesting that there are better ways for grown-ups to spend their reading time and book money than on Harry Potter, and the conversation always goes pretty much the same way: 'It's for fun. Not everything has to be Shakespeare. It's escape.'

But it's not, is it? If it were just about relaxing once in a while with a light, entertaining book then we'd all choose different ones, and read them at different times. The fact is, people are reading Harry Potter and Dan Brown for the same reasons that we're supposed to be reading important works: to engage in a creative social experience and conversation that connects otherwise atomized and alienated imaginations. Today's only shared literary experiences amongst those who've moved past mandatory high school syllabi are mitigated almost exclusively by pulp. Speculations as to "Who's a Hufflepuff and who's a Gryffindor" are guaranteed conversation-starters, whereas one of my favourite jokes in the world – "Luba Goy? Sounds like something Portnoy would do"— is essentially useless.

So, is this a victory for the blue-collar everyman over the pointy-headed intellectual stranded in the ivory tower with his Adorno Reader? Hardly. Like its cousin demagoguery in the world of politics, literary populism pretends to a defense of 'the people' whilst actually serving the economic interests of a very small elite.

Sure, stories like that of Rowling's climb up from poverty, or of local publisher Raincoast Books' securing the rights to sell her series, warm the heart. But for the most part, the development of a monolithic, largely inoffensive and easily-saleable ersatz-literature with the potential for major marketing tie-ins is a lot more profitable to publishing and retail giants than a world of small, heterogeneous publishers, authors and book retailers (though an enormous correction has been proffered to we Chapters-bashers by the very recent success of the CAW in organizing a union and attaining a first contract at the flagship Robson street store in downtown Vancouver, a feat unlikely in most small bookshops).

Our invisible success

That said, Morrison's triumph (handed out by a panel of "writers, critics and editors" whose political, ethnic and gender heterogeneity also mark enormous strides since the bad old days) is part of a growing body of evidence that suggests the Canon has been significantly democratized, as have the bodies who name it.

So, is it snobbery to suggest that we start reading serious literature again? Some would think it inexcusable to suggest that there is a serious literature that can be discussed outside of quotation marks. Then, of course, there are those who say "at least they're reading" – a noble sentiment when the subject is children barraged by video games and HDTV (catered to those with ADHD), but the worst kind of 'Let Them Eat Cake' elitism when referencing adults.

Besides, Canadians readers have a magnificent advantage: we live in a country that has produced a serious and extraordinary literary output over the past 20 years that is so out of proportion to our tiny population that the only thing more stupefying than our capacity for authoring brilliant domestic works is our propensity for spending scads of money on brainless imports like Da Vinci. "How dark the con of man," indeed.