- His Dark Materials Omnibus

- Random House (2007)

The recent release of The Golden Compass has publicized the trilogy that the film is based on: His Dark Materials, by Philip Pullman. It's also revived the controversy over the books' anti-religious theme; Christian parents are swarming into web forums to warn one another about the movie and by extension about the books as well.

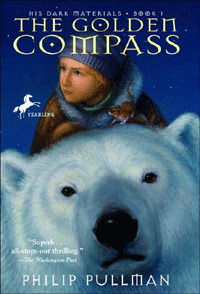

I confess I had been only dimly aware of Pullman's trilogy. He's classed as a "young adult" writer, and when the trilogy does turn up in the SF and fantasy sections of local bookstores, it looks like just more awful mass-market junk.

Shame on me for judging books by their covers (and blurbs). The controversy over the film stirred me to find a copy of The Golden Compass, and I was instantly hooked. I raced through the sequels -- The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass -- and they did not disappoint.

Pullman is a brilliantly merciless storyteller. Just when you think things can't get any worse for his 12-year-old characters Lyra and Will, they get worse. They may have some special talents and tools, but they pay a high price for them. The characters are complex, plausible, and driven by understandable motives to pay that price.

He also has a wonderful imagination, shooting off ideas and images that coalesce into alternate universes full of concrete detail, from "anbaric" lights to the metallurgic skills of polar bears.

Reactionary fantasies

All fantasy is political, and here is where Pullman upsets his adversaries. Most of the fantasy epics we know and love are safely reactionary. The plots are always about restoring some dynasty to its lost throne in a picturesque country that's never experienced an election, much less a U.S.-style primary campaign. The fantasy kingdom may have evil aristocrats, wizards and priests, but the good guys will eventually win.

His Dark Materials isn't about the restoration of the old order but the creation of a new one -- the overthrow of God's Kingdom and the establishment of the Republic of Heaven. This may seem like wicked Bolshevism, but it really reflects Pullman's literary influences: a couple of radicals named John Milton and William Blake.

Pullman happily admits his debt to Paradise Lost and the poetic vision of Blake. Milton was a hell of a science-fiction author, with a story well worth stealing. His Lucifer is a spacefaring angel, flying between Heaven, Hell and Earth.

While God is the ostensible hero of Paradise Lost, Lucifer certainly gets the best lines, and he's far more interesting as a character than his mealy-mouthed and arbitrary ex-boss, who shrugs off his ultimate responsibility for Adam and Eve's fall.

'Of the Devil's party'

It's also worth remembering that John Milton was a staunch Cromwellian and anti-monarchist, who narrowly escaped punishment when Charles II took over in the Restoration.

William Blake, similarly, dreamed of a cosmos freed of mechanistic Newtonian physics and the oppressive patriarchy of "Nobodaddy," the belching, farting God of Blake's mythology. Blake saw the American Revolution as the portent of a new world, and the epigraph in The Amber Spyglass is from Blake's America: A Prophecy.

Blake also famously observed, "The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet, and of the Devil's party without knowing it."

So Pullman's young readers may not realize it, but they are being well prepared for their university English courses. (Whether their professors are prepared for Pullmanites is another question.)

Various universe

They are also being well prepared for some pretty sophisticated post-Newtonian physics. While many of his elements seem like straight fantasy, Pullman's tale is based on the "many worlds" theory, which argues that every time an atomic particle can go one way or the other, it goes both ways, creating a new universe in the process.

On top of this he makes dark matter -- a recent conjecture, not yet directly observed -- an active character in his story. In Pullman's cosmology, "God" is simply the first angel to form out of dark matter, and he establishes an enormous con game to maintain his supremacy.

The first angelic revolt having failed, the universes are now ruled by Metatron, a once-human angel who acts as the prime minister of a doddering and feeble deity. (Pullman's God is also reminiscent of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's "Very Old Man with Enormous Wings." Revolt against such a regime isn't easy, but it's possible -- even mandatory.

Revisiting Christianity's family quarrels

So this is what the parents are anxious about -- an ideas-based thriller that will introduce their kids to Christianity's family quarrels going back four centuries.

More sophisticated Christians have no problem with the trilogy. They may recall Milton's lines in Areopagitica, his classic defence of free speech:

"I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary . . . that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary."

By that token, Pullman's characters -- and readers -- must be pure indeed by trilogy's end. He follows the logic of his story wherever it leads, and we must follow whether we like it or not.

Many kids must cry by the trilogy's end, but they have also experienced a rare sensation: an intelligent author has respected them, treated them like adults capable of dealing with adult issues. (Would that more writers for adults would do the same for their readers.)

I haven't seen the movie yet, but its success or failure is beside the point. His Dark Materials is that rarity, a popular fiction (15 million copies sold) that refuses to pander to its readers. That achievement alone makes it worth reading . . . and thinking about.