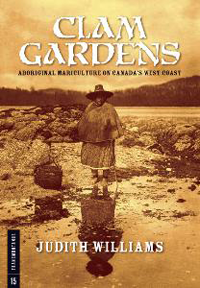

- Clam Gardens

- New Star/Transmontanus (2006)

- Bookstore Finder

Years ago, an old maple toppled in an Indian Arm waterfront park near where I live. Its fall exposed a large midden of oyster and clam shells -- a reminder that what is now just a pretty view was once a source of food for a whole community.

Our present-day fish farms pollute the waters and kill off the wild salmon. Judith Williams's new book Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture on Canada's West Coast shows us how the First Nations did it first and did it better. The clam gardens are a centuries-old sustainable industry that still helps to feed coastal communities.

Williams tells the story as a quest for something hidden in plain sight. While doing research for another project in the early 1990s, she'd learned about rock walls erected in Waiatt Bay on Quadra Island. Her sources were modern Sliammon who still harvest the butter clams grown inside those walls.

Having seen the walls, Williams began a years-long investigation. Similar walls can be found in bays and coves all over the central coast -- more than 350 clam gardens in the Broughton Archipelago alone. Many are still in use, and kept in repair. Others simply mark long-abandoned village sites.

Gardens of 'imagination'

Williams tried to interest the archeologists at the B.C. Heritage Conservation Department. They told her no evidence existed for an aboriginal mariculture; the Waiatt Bay wall didn't exist -- and if it did, it was a salmon trap.

Persisting, Williams explored the central coast and found supporters as well as more walls. People who live on the central coast know about the clam gardens. The trouble is that hardly anyone lives on the central coast nowadays. To most British Columbians, the coast between Powell River and Prince Rupert is just so much empty scenery, a tourist attraction for the boaters and cruise ships.

But the neglect of this aboriginal industry goes all the way back to the days of anthropologist Franz Boas, who studied coastal culture a century ago. Williams speculates, with some reason, that Boas was simply more interested in the male-dominated aspects of that culture. What the women did wasn't as important as the ceremonies and arts of the men.

Yet the more she learned, the more Williams came to believe that the clam gardens reflected a larger, older and more sophisticated culture than Boas had recognized.

The basic structure of a clam garden is simple but elegant: a wall of stones and boulders set at the extreme low-tide contour of a bay. Sediment gathers within the wall, creating "fluffy" sand that butter clams flourish in. The tides carry nutrients over the wall. Clams and other shellfish multiply. At extreme low tides in summer and winter, the gardens are exposed. All you have to do to harvest the clams is walk out with a digging stick and a container -- preferably in winter, in the middle of the night, when the danger of red-tide poisoning is least. The clams can be easily dried and strung together for storage.

Williams points out that clam digging may have been women's and children's work, but building the walls required plenty of brute strength. Organized teams of men had to carry or roll the boulders out to the low-tide line at precise times of year. They had to maintain the walls, and ensure that gaps would permit canoe access even at very low tides.

So the coastal populations in those pre-European times must have been far larger than they are today, simply to provide the manpower. And the size of the population also created a good reason for building the clam gardens in the first place: a lot of mouths to feed.

Evidence challenges assumptions

"What population densities might provoke and accomplish such labour?" Williams asks. "Recently anthropologists have suggested that early estimates of 100,000 people on the Northwest Coast had been gross underestimates."

What happened to them? While Williams doesn't explore that question, we know that a smallpox pandemic swept the coast from 1862 to 1865. An estimated 60,000 aboriginals lived on the coast, and 20,000 of them are believed to have died. It was B.C.'s greatest single documented catastrophe.

Some historians think smallpox had reached B.C. before, perhaps in the decades just before Captain Cook and then Captain Vancouver explored the coast in the late 18th century. The disease could well have followed aboriginal trade routes north from Mexico, just as the 1862 outbreak originated with a traveller from San Francisco.

If so, then a population of far more than 100,000 had been living on a now-empty shore. They had sustained their numbers by a highly sophisticated mariculture, using techniques that may have been thousands of years old. Even after suffering hideous losses, the coastal peoples had held on to their technology. Over generations, that technology helped them begin to recover.

Clam Gardens is therefore a special book. Like the midden under the maple tree, it makes us look at our own landscape and history in a different light. The boaters and cruise-ship passengers roving this coast are gazing not just at scenery, but at the sites of a great, lost civilization. ![]()