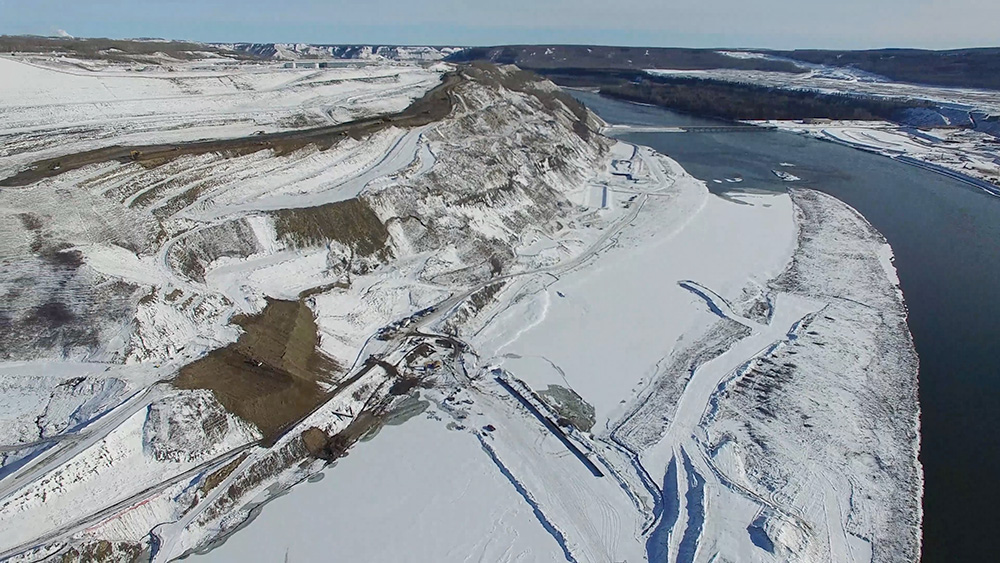

It’s a lot of work getting a riverbank ready to hold a 15-storey earthfill dam. That’s what Site C crews have been focused on for the last 21 months. It’s mostly prep-work, so there are only a few permanent installations. Everything else will be removed after construction.

I’ve seen the dam site a few times over the last year. Each time they’ve logged farther, dug deeper and built more structures. But it’s clear this project is still in the early stages, despite all the activity.

So this time I’m here to try and answer one of your big questions about Site C, as The Tyee and Discourse Media promised to do.

Has Premier Christy Clark achieved her goal of ensuring Site C will be “past the point of no return” by the May 9 election? Or do voters — and the next government — still have a choice?

Here’s a rundown of what’s there. There’s a sleek bridge crossing the Peace River, with new roads on either side. But the bridge is slated to be removed once construction is complete. There’s another bridge crossing the Moberly River, also temporary. A concrete plant is sitting where the substation (the thing the turbines will spin power into) will be built, so it too is temporary. The resort-like, 1,600-person camp with its movie theatre, spiritual centre, hair salon and coffee shop will also be packed up after construction’s finished. Concrete “curtains” in the river banks help prevent seepage; they’re permanent. And a lot of work has gone into re-shaping the landscape. Hills have been trucked away, islets moved and trees and brush cut.

But what looks like a lot of work is really just the start. Based on BC Hydro’s construction plan — and given some setbacks due to unstable ground — work is expected to still be in this preparation stage by the election.

A lot of money has been spent — an estimated $1.5 to $2 billion, with another $2 billion committed in contracts. That’s less than half the budgeted $8.8-billion cost.

But that’s still not enough to convince some critics that Clark is on track to achieve her goal of making it impossible to cancel the most costly megaproject in the province’s history.

It’s not just a matter of how much money has been spent, says Ken Boon, one of nine landowners whose property was expropriated by BC Hydro just before Christmas. Another 20 or so will be expropriated before the project is done. The Boons have to be gone by May 31 — three weeks after the election. “The optics of us being kicked out of the house right in front of the election, that wouldn’t look good to Christy, eh?” he notes.

“The trouble is that they’re just looking at the balance sheet. They see X-amount of dollars spent and say ‘Oh, well you can’t go back now,’” says Boon.

“But there’s a lot more to it than just economics. There’s the natural capital, and all the cumulative impacts, the impacts on First Nations. Loss of biodiversity, and agriculture. It just goes on and on. And you gotta value those things.”

First Nations have lived in the Peace Valley that will be flooded for more than 10,000 years. The cost to their treaty rights, ways of life and history are significant and complex. (We’ll focus on this issue in a coming article.)

Some economists think Clark has won, and it’s too late to turn back now even if Site C isn’t needed.

Both former BC Hydro CEO Marc Eliesen, and Harry Swain, head of the joint federal-provincial government review of Site C, say the smart move is still to cancel the project.

“There’s no business case for building Site C,” Eliesen says. “But there is a business case for stopping it.”

The economic principle of sunk costs says that what’s already been spent on a project should be irrelevant to future decisions. Only remaining expenses should be considered when evaluating return on investment. Which explains why some who opposed the dam at the beginning now say it should continue.

But even considering the sunk costs, Swain and Eliesen say it’s still financially advantageous to stop construction now.

First, the power isn’t needed provincially and BC Hydro hasn’t yet signed on any buyers, Eliesen says. So there isn’t a reliable revenue source to make a return on the investment. “Selling the power at spot prices can’t justify the huge expense. We will end up with a stranded asset, a white elephant.”

Swain agrees, saying that spot market power sales, worth an average $30 per megawatt hour, don’t justify spending any more than $2 billion.

“My back of the envelope arithmetic shows that this project, which will cost $9 billion, has a net-present value of about $2 billion. So at any point up to the irrevocable commitment of $7 billion, we’d be better off stopping,” Swain says.

“If you take the only sales that are available as far as we can see, and multiply that by 5,100 gigawatt hours (Site C’s projected capacity), that gives you the revenue side of your equation,” he says. “Then you figure out what it costs, and even if you accept the insane financing package that BC Hydro and the government have put forward — that is, a 70-year amortization at three per cent — you’re still a big time loser.”

Second, BC Hydro is already carrying an unprecedented $18 billion in debt. That will increase by almost 50 per cent when Site C is completed. Customers will have to cover huge interest costs and Hydro’s debt could result in a credit rating downgrade for the province, increasing interest costs for all provincial borrowing.

“The only solution is a massive increase in electricity rates. Major jobs will be lost,” Eliesen says. “There’s no question: when you have a massive increase in electricity rates, businesses leave the country.”

Swain predicts the project will also lead to higher taxes. “People are going to wind up paying for a stranded asset through their taxes for years and years to come. Hydro will not have the financial capacity to pay it, so it will fall to the guarantors of their debt, that is, the taxpayers.”

Third, large dams almost always go over budget. Manitoba Hydro’s Keeyask dam is 34 per cent over budget; Newfoundland’s Muskrat Falls project costs have almost doubled to $11.2 billion.

The geotechnical challenges at Site C almost guarantee budget overruns, according to Eliesen.

“The reports have always made reference to the faulty soil, unstable soil in the area,” he says. “There’s no way you can get a handle on it until you actually start construction, and in this particular case we’re already seeing, even on a preliminary basis, how unstable the soil is upon which you’ve got a major generating station.”

He’s referring to a 400-metre crack that appeared in February, near an anchor point for the dam. Work was temporarily stopped on the north bank as crews attempted to address the instability. Given the geology of the area, some have suggested the ground will never be stabilized.

“Can it be solved? I’m sure piles of money may solve the problem, but this will be one of the major factors leading to escalating cost on Site C,” Eliesen says.

Others agree. A contractor, who asked for anonymity to protect his ability to get work on the project, said cost overruns bring pressure on contractors to bid lower and lower. “They keep telling us we’re too high, but our bids are accepted elsewhere, so we know our prices are in line.”

“The whole project has been a ‘throw money at it and it will get better’ sort of mindset,” says a transport contractor. “But you can’t fix a geotechnical problem.”

The first two Peace River dams are anchored to bedrock, but the area around Site C is made of sedimentary clay and shale, and is prone to landslides.

A look at the Peace River topography demonstrates the way the ground slopes and slides over time. Vegetation stabilizes the top layer and wicks water out of the ground. Now with the land at Site C cleared, that stability is gone. Contractors have had a hard time even building an access road on the north slope, because the clay is so slippery and unstable.

“They’re trying to stabilize mud,” warns the transport contractor.

“Cautionary examples such as the Mount Polley disaster demonstrate that clay sedimentary basins are the absolute worst places to construct dam reservoirs,” says retired regional director Arthur Hadland. “Old mud is not safe bedrock material!”

BC Hydro reviewed Site C in detail under Eliesen’s leadership in the early 1990s. “The board of BC Hydro took the position that for reasons related to First Nations’ rights, for the environment, and also for the cost, that we would not ever proceed with Site C,” Eliesen said.

So what changed in 20 years to make the board go ahead with the twice-reviewed, twice-rejected project?

“I have no idea whatsoever,” Eliesen says. “In my view, the directors of BC Hydro have abdicated their fiduciary and legislative responsibility. They have allowed primarily the premier and the minister of energy to run BC Hydro. In my view they’re running it into the ground with dire consequences for the future.”

“I believe the only reason for Site C going ahead is that the premier and Liberal Party of BC want to be able to refer to a project. Since there are no LNG projects, which they’ve promised for the last four or five years, this is the one project they can say has gone ahead. Whether it makes economic sense is not important to them.”

BC Hydro was unavailable for an interview or tour of the Site C project.

There will be a cost to stop the project, but it’s hard to know exactly what it is.

Contracts generally have termination clauses that specify penalties in the event of cancellation. Experts in government contracts say there’s no way to estimate what those penalties are, since every contract is uniquely negotiated, but that it’s safe to assume penalties won’t be equal to the full contract value.

Bruce Pardy is a law professor at Queen’s University. He investigated government’s ability to cancel contracts while examining Ontario’s sky-high energy prices.

“There’s a whole raft of long-term alternative energy contracts that the Ontario government entered into. The contracts are 20 years long and the rates are greatly inflated. Power costs have jumped, and everyone’s asking what can we do about all these costs? Surely the contracts can be revisited,” Pardy says. “So the question was, can they be revisited? The answer in short, is yes, they can.”

Legislative supremacy overrules any contract or property law, as long as the government has jurisdiction over the contract and doesn’t violate a constitutionally protected right. Governments rarely pass laws to cancel contracts, but the ability does give them bargaining power to renegotiate, Pardy says.

“I think it is politically much easier for a new government to contemplate cancelling an old government’s contracts than it is for a current government to contemplate cancelling its own contracts,” Pardy says. But even an incumbent government can use the threat to gain bargaining power. “As a government you could bring them back to the table and say look we made this contract with you, but we don’t like it now, we’d like to renegotiate.”

The Green Party of BC has consistently called for Site C to be cancelled, calling it “environmentally, economically and socially reckless.” The NDP has said they would send the project to the BC Utilities Commission for independent review if elected, something the Liberal government has refused to do.

“Whatever it costs, it’s worth it to the taxpayer and ratepayer,” Eliesen says, “because the business case clearly shows that Site C should not be built.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, BC Election 2017, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: