Is a grand reckoning for Exxon Mobil — and the oilsands it invests in — about to begin? We might know in the coming weeks, when New York judge Barry Ostrager delivers a decision about whether the oil major is guilty of misleading its investors over climate change.

I was at the “People of the State of New York Vs. Exxon Mobil” trial this week as 2.5 weeks of testimony, cross-examination and legal arguments began to wind down; closing arguments were heard on Thursday. And though the lawsuit focuses specifically on whether Exxon properly disclosed the massive financial risks it could face because of climate change, it was impossible to ignore the larger context for this unprecedented trial of an oil major.

Here was a company that had for years sowed doubt about climate change; poured tens of billions of dollars into Alberta’s climate-destroying oilsands; and threw its full lobbying weight into dismantling the Barack Obama administration’s effort to limit the flow of oilsands into the U.S., as The Tyee documented in a 15-part series reported from Washington, DC.

Now, in Room 232 of the New York State Supreme Court, before a draped American flag and “In God We Trust” spelled on the courtroom wall, one of the world’s largest and most powerful companies was being sued by the state’s Attorney General for allegedly misleading investors about the ticking financial time bomb of its high-carbon investments — many of which are concentrated in northern Alberta.

“Canadian oilsands is an asset that has higher costs and lower margins,” said the Attorney General’s office lawyer Kevin Wallace at one point in the wood-panelled courtroom. He was referencing a 2016 analyst note from BMO raising concerns about the profitability of Exxon’s oilsands operations. Wallace was trying to build the case that Exxon had banked its future on one of the planet’s most expensive and climate-exposed oil sectors and then downplayed those risks to investors.

But Exxon’s expert witness Marc Zenner wasn’t fazed in the slightest. “That is an asset that Exxon Mobil has and the analyst has an opinion about these assets,” Zenner explained flatly to the courtroom.

Then it was Exxon attorney Justin Anderson’s turn to question Zenner. “This [BMO] analyst is [writing] that those are higher cost operations, do you know those to be higher cost operations?” Anderson said of Exxon’s investment in the oilsands. “I haven’t investigated it sir,” Zenner said.

The Exxon attorney continued his questions, making the argument that investors had never considered Exxon’s heavy potential exposure to climate change regulations or a global low-carbon transition that could kill off demand for oilsands altogether to be a serious factor in how they valued the company. “This analyst is saying [greenhouse gas] costs are driving those costs?” Anderson said. “Any reference to climate regulatory risk?”

“No sir,” Zenner replied both times.

These dry, technical and often arcane legal exchanges could seem maddingly beside the point, given the catastrophic dangers that a warming climate poses to billions of people around the world — not to mention the thousands of lives it is already disrupting across Canada and the U.S. But observers such as Stephen Kretzmann of the group Oil Change International see this lawsuit as the thin wedge of a looming climate judgement. “Exxon has used every tool in the book to stop any progress on the clean energy transition,” he said, adding the “social licence for the industry is really being full withdrawn.”

Kretzmann and I met for the first time back in 2011, when as a freshman reporter with The Tyee I flew to Washington to investigate how the Canadian and Alberta governments were working with Exxon and other oil companies to block the Obama administration’s clean energy transition. After a week of meeting with oil lobbyists on K Street and at the Republican Capitol Hill Club, I learned that clean energy regulations posed a massive financial threat to the Alberta oilsands, and that the industry would do whatever it took to keep its profits flowing.

That could mean torpedoing something called a low carbon fuel standard that would have imposed climate penalties on Alberta’s high-carbon oil. “Ultimately, we got that deleted,” said Tom Corcoran, a lobbyist with the Center for North American Energy Security, a little-known industry group supported at the time by Exxon and other oil majors.

As Kretzmann explained to me at the time in Oil Change International’s small Washington office, companies like Exxon were running out of places to add new oil reserves to their books. They needed the oilsands to keep their stock prices afloat. “There are financial incentives that encourage the industry to go into places like tar sands, deepwater and high Arctic,” he said.

That might help explain Exxon’s aggressive lobbying, and also the fact that it was presenting one measurement of its climate risk to investors, while using a separate, looser measurement in private to help justify $33 billion in oilsands investments. Around the time I visited Washington, executives within Exxon were suggesting the company stop this practice of using separate climate measurements. Potentially that was because Exxon’s vast oilsands operations were “vulnerable” to future climate regulations, as the company’s vice-president of environmental policy and planning warned internally in 2011.

Concerns like this from top Exxon executives are a key piece of evidence in the Attorney General’s lawsuit against the company. “You can’t say one thing in public and then do something different in your internal analysis, and that’s really the crux of [the case],” said Rob Schuwerk, North America executive director for the financial think tank Carbon Tracker.

This wouldn’t be the first time that Exxon’s public statements don’t align with its private actions. The company did some of the earliest scientific research on global warming back in the 1970s, as a groundbreaking investigation from InsideClimate News revealed in 2015. Despite an Exxon scientist warning in 1981 that climate change could cause “effects which will indeed be catastrophic — at least for a substantial fraction of the earth’s population,” the company worked for years with Chevron, BP, Shell and other fossil fuel producers on a public relations campaign suggesting doubt about whether global warming is even real.

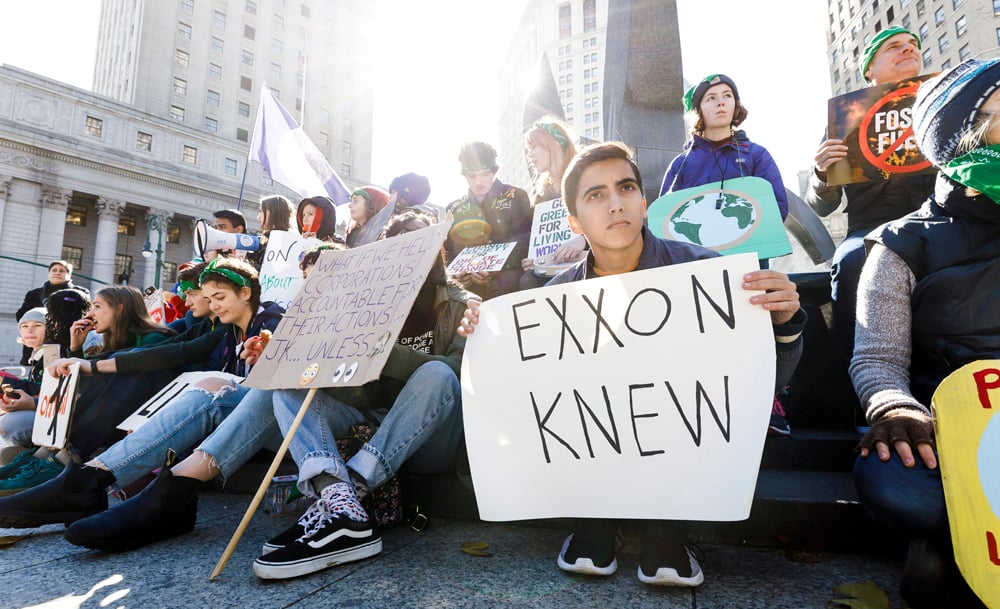

Exxon was not being sued for sowing lasting public confusion about the greatest existential challenge of our time, but its scientific denial loomed large over the trial. Protesters outside the New York Supreme Court held a banner reading “#ExxonKnew” in reference to the InsideClimate News revelations. And Nicholas Kusnetz, a reporter with the outlet who attended the entire trial and filed numerous comprehensive dispatches, said the lawsuit has significance beyond the narrow financial issues actually being argued in the courtroom.

“It’s the first major climate change case to go to trial at all in the U.S. and it’s also featuring Exxon, the biggest American oil and gas company, which has played such a prominent role, not just in energy and oil and gas, but in the industry’s role in shaping public opinion and political action on climate change,” he said.

What happens now that the trial is officially over is hard to predict. A ruling for or against Exxon by Judge Ostrager might end up only being relevant in a limited legal and financial sense and have little impact in our wider fight against climate change. Or it could be the beginning of the legal and moral reckoning that many observers think Exxon and other producers of high-carbon oilsands have been doing everything in their power to forestall.

“Yes, these companies produced revenues and jobs, but at the same time they weren’t paying the real cost of the damage they were doing to people, to our environment and to public infrastructure,” said David Estrin, a law professor at Toronto’s York University and an environmental law specialist with over 30 years’ experience. “They need to recognize that their days are limited, they have to do their share to transition to non-carbon energy, and if they don’t want to do that they should be out of business.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: