[Editor’s note: It’s a well-documented fact that Vancouver is a notoriously lonely city. And for some, these pandemic years have only heightened a widely felt sense of social isolation that feels as unique to this city as its mountains-and-ocean beauty. But it doesn’t have to be this way. In this final instalment of her three-part solutions journalism series, The Tyee’s Tula Immersion Journalism Fellow Kaitlyn Fung brings us to the frontlines of Vancouver’s burgeoning mutual aid community of volunteers who are stocking community fridges, bringing needed supplies to unhoused people, sharing personal protective equipment with those who need it, and creating space for Vancouver’s Black community to gather.]

In the lane behind 4040 Victoria Dr. in East Vancouver, there’s a free fridge sitting in the alley.

But it’s not just a random alleyway find. It’s already plugged in and works perfectly well. And the fridge itself isn’t free for the taking — but the food inside it is. The same is true of the wooden pantry beside it, which features a cheerful pastel paint job and a shelf full of bread. Friendly signage welcomes visitors in multiple languages, telling people to “take what you need, leave what you can.”

This fridge is a deliberate act of community care — and part of a rising tide of mutual aid in Vancouver that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Early pandemic support in the way of having enough food, child care or income was often difficult to find when the coronavirus shut down schools and workplaces, and ensuing panic first hit the city. While governments began offering financial relief, numerous social services were still suspended or reduced amid efforts to limit the spread of the virus. Their absence worsened existing precarity around income, housing, food and other basic necessities.

Many people couldn’t afford to wait for help. So, like others spurred by the pandemic, they took it upon themselves to take care of each other, and the people in their communities. In other words, they practiced mutual aid — a reciprocal, voluntary exchange of resources for the benefit of all members of a community. Mutual aid is characterized by its non-hierarchical, grassroots structure. People volunteer their time and resources to participate in mutual aid efforts, sometimes raising money through crowdfunding or community calls for donations.

In Vancouver, support groups formed across neighbourhoods and the city itself, connecting those with the desire and capacity to help with anyone who needed it. Organizing these initiatives took place online through Facebook, WhatsApp and other social media. People on the networks exchanged everything from extra supplies to phone numbers for compassionate chats amid isolation. These efforts became vital lifelines.

“The crises that are happening can leave us so distraught,” says Zhanger, one person who chatted about mutual aid with me. “Doing this work is one of the ways I can feel — like I don't just sit here and think about how awful things are.”

'I’m trying to practice what I hope will grow’

The Vancouver Community Fridge Project, which supports a network of community fridges like the one on Victoria Drive, exemplifies the direct impact of mutual aid that people often require for their everyday survival. Keeping public fridges and pantries stocked with free food, which can be shared or accessed by anyone, can alleviate immediate hunger.

“They’re some of the lowest-barrier ways to get food to people,” says Sydney, a volunteer with the Vancouver Community Fridge Project. “There’s no applications, you don’t have to go through an organization, there’s no qualifications. The only real barrier is being able to physically get to the fridge.”

Some fridges are located at individual residences while others are co-ordinated with a host organization, like the community fridge at Little Mountain Neighbourhood House on Main Street. Operation of each fridge is fairly autonomous, so the Vancouver Community Fridge Project focuses on distributing food and other beneficial items for the pantries, like menstrual hygiene products or hand sanitizer, wherever needed.

People seem to immediately understand the significance of providing universal necessities like food, even if they haven’t had experience with mutual aid. Part of that, says Sydney, is because many are already familiar with charity programs like food banks and soup kitchens — but they emphasize that mutual aid is not charity.

Instead of relying on government or non-profit agencies, which Sydney says can be mired in bureaucratic processes, mutual aid is driven by grassroots action between peers. For Sydney, this interdependence “feels like how people are supposed to operate, like recognizing that we’re interconnected.”

“So when I'm engaging in mutual aid networks this way,” they add, “I'm trying to practice what I hope will grow.”

Keeping the network decentralized is crucial to them and the small collective of volunteers who support the Vancouver Community Fridge Project. By forgoing hierarchical structure and formal positions, it avoids concentrating power within a particular institution or person. People can come and go, adjusting their involvement as needed. This is also why Sydney and several others I interviewed for this story declined to share their last names for publication — it was important to them to showcase the community-mindedness at the heart of mutual aid without centering themselves.

But it’s tough when capacity fluctuates and demand persists. Every community fridge is well-used, says Sydney, but some are “incredibly difficult to keep up with,” like the one on Victoria Drive. After shipping delays last winter hiked up food prices, usage spiked at every fridge.

“Some of the people who used to drop off food are now struggling with food security,” says Sydney. “There's not only an incredibly heightened need, there's also less ability from the community to address that need.”

When I visit the fridge by Victoria Drive in late November, the selection that day is modest, including some canned food in the fridge alongside the bread in the pantry. Someone on an electric scooter also arrives to glance at the options, but leaves without dismounting when none are of interest.

While ensuring long-term sustainability is challenging, the needs that mutual aid aims to address — and the conditions that trigger them — haven’t disappeared. Instead, the pandemic has only further exacerbated them.

Listen to the activities of the Distro Disco on a busy Saturday this fall.

Overlapping crises

One Saturday morning at Trout Lake, past the nearby farmers market, a different kind of vendor sets up. They arrive in style — with a repurposed shuttle bus, and a disco ball. This is the Distro Disco, a mobile free store offering necessities for unhoused people in Vancouver.

Plastic bins are unloaded among tables, their labels corresponding with items listed on a whiteboard. Ideally, the bins will soon fill with donations of these items — batteries, tarps, lights, toiletries and more. Meanwhile, volunteers sort clothing by size, warmth and weatherproof quality.

Donation drives like these are held on the first Saturday of every month. They help the Distro Disco replenish its inventory.

Distro Disco began in 2020, catalyzed by the pandemic. But it’s also “a response to overlapping crises” already happening, says Courtney, a Distro Disco volunteer.

Zhanger, another volunteer, echoes Courtney’s point. Both of them highlight how the pandemic, toxic drug supply, climate emergency and housing unaffordability now converge into ongoing harm in Vancouver.

In the summer of 2020, COVID-19 exposures hindered Downtown Eastside organizations from sheltering residents from wildfire smoke. It put additional pressure on a neighbourhood where many are already without adequate housing to safely self-isolate or support each other.

These crises are also affecting people disproportionately. The pandemic had a dire impact on racialized and low-income communities, from increased racism to facing the highest rates of COVID-19 infections.

Considering these emergencies, Distro Disco’s mobility is indispensable for transporting supplies anywhere needed at critical moments — including heat waves, displacement from SRO building fires, and multiple evictions of encampment residents from locations like CRAB Park and Oppenheimer Park amidst a lack of suitable housing options.

Courtney summarizes it this way. “We live in a really wealthy city, and it seems just untenable that there are people on the street when there's so much wealth and resources here. We just try and be a link between those two things.”

For Zhanger, mutual aid prioritizes “collectivism over our capitalist values.” They describe chatting with a client who shared that “a few years ago, when she had more, she was the one out on the street doing stuff, giving and helping people.”

“That was really powerful,” they say, “Just to think that, if I, or any of us, are ever in need one day, that maybe there will be a collective or just a whole community that really cares about supporting those who have less.”

Prioritizing that care, says Courtney, includes changing “the donation mentality of cleaning out your garage to that community care model of ‘pick up an extra thing’ — like can you pick up a tent this week for someone who doesn't have shelter?”

Interwoven relationships of care are central to Disco Distro and the communities that anchor it. Zhanger underlines how one of the co-founders, Charlie Hannah, observed “a lot of the mutual aid and care and leadership in the Downtown Eastside and was quite inspired by that — that this is a community that has already been practicing and exhibiting these values.”

That work gained wider traction when the pandemic began. Renewed awareness also came during media attention on the street sweeps and fires affecting the Downtown Eastside, says Courtney, but “it doesn’t go away just because it’s not in the news.”

Now, as society pushes for normalcy despite ongoing crises in a pandemic, many people feel left even further behind by the systems that failed them in the first place.

“The COVID pandemic just laid bare that gap or inability of governments and institutions to intervene,” says Courtney.

An act of rebellion

Under the shade of a tent on a bright autumn afternoon by Commercial Drive, curious park goers stop by an impressive pandemic display at Grandview Park.

On the tables before them lies a bounty of personal protective equipment, including N95 masks, rapid testing kits and hand sanitizer. Another box contains 3D-printed “ear savers” for adjusting the fit of one’s mask. Everything is brand new and free.

Each pile of equipment is labelled in Vietnamese, Chinese and English, with masks sorted by size. Volunteers share tips about usage and general COVID-19 safety. Additional volunteers offer Cantonese, Mandarin and Vietnamese language interpretation.

Since starting in May 2022, Masks4EastVan has distributed thousands of free masks like this, through pop-up events and home deliveries. While based in East Vancouver, they also try to serve remote areas of the province by mail.

Co-organizers Jane Shi and Vivian Ly say it’s a direct response to the lack of mask mandate and resources being provided by the government.

“For me, it's a very rebellious act,” says Shi. She and Ly live with multiple disabilities and have spent the pandemic worried for their health in public spaces. “Doing this kind of specific, broad disabled mutual aid work is saying: all the levels of government, but also including non-profits, have abandoned us."

As public health authorities gradually remove protective measures — like dropping mask mandates and eliminating self-isolation requirements if COVID-positive — many find these changes unclear and concerning during a season of escalating respiratory illnesses. Shi and Ly are concerned that the ongoing removal of public health restrictions to prevent the spread of the coronavirus have left disabled and immunocompromised people behind.

Expecting people to accept the level of viral risk or to remain home and isolate indefinitely, especially without adequate resources, feels devoid of empathy to Shi. “The idea that a lot of people have around not masking in public is like, ‘Oh, I'm not immunocompromised, I'm not a senior, I don't need this. Or I don't have any disabled people in my life,’ which is very unfortunate for them, because we're pretty cool.”

“They probably do have disabled people in their life, they just might not be told about that,” adds Ly. “Because of the ableism.”

While navigating ableism like this, including at the level of government and public health institutions, sharing free masks becomes a broader statement about surviving not just the virus, but uncaring systems, too.

In Ly’s words: “It’s literally injustice, it’s literally eugenics. It's literally being okay with people dying — so that’s what mutual aid is rebelling against.”

The community response to Masks4EastVan seems to indicate a swell of support and desire to see people cared for in a different way. While distributing at Pandora Park in June, demand was so high they ran out of masks within 15 minutes. Currently, their fundraiser to keep supporting the community with more masks is continuing through the winter.

“It’s all folks — BIPOC, queer and trans folks, disabled folks, folks who have been long left behind, even more so during the pandemic,” says Ly of the people who often show up to this work. “It’s out of necessity that we’re showing up.”

Shi points out that “multiply marginalized communities” have been doing mutual aid for a long time, and that it has historically been practiced by Black, Indigenous and racialized communities. It is also frequently undermined by governments and non-profit institutions.

But mutual aid has fundamentally always been for everyone, even in spite of harm, says Ly. “I really strongly believe that I don't have to even like a person to care about their survival.”

As a disabled, neurodivergent and queer person of colour, Ly has witnessed plenty of “lateral violence” like racism within disabled communities, or ableism within queer and trans communities — but it doesn’t change the importance of caring “about community safety, and about disability justice.”

“I’m still going to care about you, if you have a mask for safety, if you have food or a ride to the doctor’s office,” says Ly. “I don’t think we should be prescribing limits to our care, in that sense, because that is a really capitalist, colonial mindset.”

Changing these mindsets, and the systems they’re rooted in, is beyond the scope of any individual project. But mutual aid approaches allow for survival rooted in resistance, and the possibility of something better.

“What are we even waiting for in the end?” asks Ly, adding that conventional approaches, like from governments or charities, often perpetuate harm against marginalized people by creating a “reliance on an unequal power structure” instead of a shared commitment to care.

“For me, it's always been reciprocity,” says Ly. “It's not ‘I'm helping you’ — we're helping each other.”

Scholars like Dean Spade, author of Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next), have also written extensively about mutual aid and its common distinctions from charities, non-profits and social service organizations. But ultimately, in Spade’s words, “Mutual aid is the radical act of caring for each other while working to change the world.”

In a world where harm is compounded from oppressive systems, it takes entire communities to survive it. But the same is true for transforming it, too.

“Mutual aid is not about merely survival,” says Shi, “but helping community to thrive.”

Listen to the Vancouver Black Library as volunteers sort through donated books for the library’s collection, while jazz music plays in the background.

Dreaming up a better future

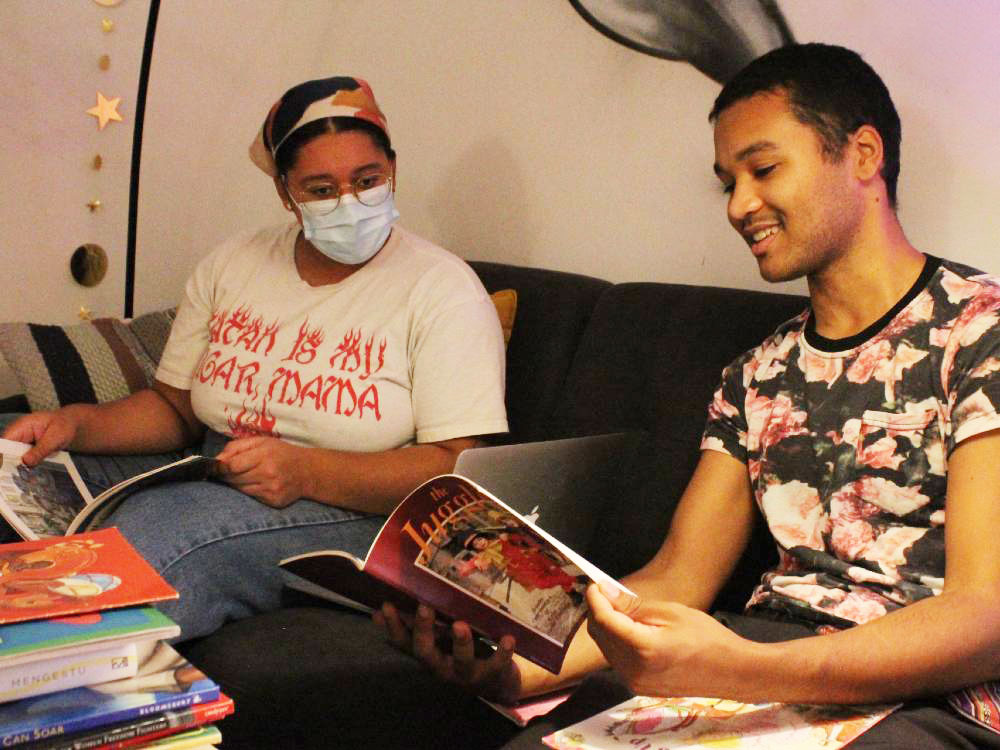

At the end of a winding basement hallway in Chinatown, boisterous laughter echoes. Following it leads to a cozy paradise of books, warm lights and community.

With piles of books in hand, people make themselves at home on the couch or the long wooden table, where even the chairs have snug knitted socks. From the current playlist on rotation, jazz musician Charles Mingus croons a refrain of freedom underneath the room’s lively chatter.

Stickers with handwritten call numbers line every book spine on the shelves. More will ensue from this cataloguing party, as volunteers sort donations for the collection based on what reflects their community’s interests.

This is the Vancouver Black Library, dedicated to providing resources and workspace for Black, Indigenous and other community members of colour. Established largely through crowd-funded donations and supported by volunteers, it is both an outcome and a celebration of mutual aid.

The Vancouver Black Library’s founder Maya Preshyon loves when people say they like the way it feels here. Since she first envisioned the library, designing the space to be “somewhere that you feel good” was always a priority.

Currently an undergraduate student studying social work at the University of British Columbia, the idea for a library emerged out of Preshyon’s experiences with other arts and music spaces, where she never “felt welcome or felt represented.” It was especially isolating for her with so few cultural hubs for Black communities in Vancouver.

But mutual aid, including over $50,000 in crowdsourced funds, now enables her to realize the community space of her dreams. That dreaming remains core to the library’s purpose, to co-create possibilities that centre joy.

“Dreaming up a better future is the way we frame everything that we do,” says Preshyon.

It’s something she often has to remind people about whenever she’s asked about the library. “When we were first coming up, a lot of people, like the big media outlets, older people — they wanted to talk about VBL in a framework of like, tell us about what happened in Hogan's Alley,” says Preshyon. “Tell us about the history of what's gone. Tell us about your struggles.”

The library’s Chinatown location, inside the Sun Wah Centre, honours its connection to the nearby Hogan’s Alley — the city’s historic Black neighbourhood scattered by racist development policies.

While addressing those questions remains important, Preshyon always follows up by emphasizing the library “is definitely a lot more about Black futures, and creating and dreaming up a better future. And we love speculative fiction here.” Whether in its goals or on its shelves, she says, the library is further inspired by the expansiveness of genres like Afrofuturism and Indigenous futurism.

Ambitious plans for the library’s future include plentiful opportunities to host whatever the community needs — including study groups, live event performances, skill-sharing workshops and other programming — for free or as low-barrier as possible.

“It could be a criticism that sometimes we think way bigger than what's right in front of us, but you have to imagine it to ever do it,” says Preshyon.

But that imagination often plays a big role in mutual aid. In a lot of contexts, “what happens on the other side is invisible, as it should be,” says Preshyon, referring to survival fundraisers organized for individuals who need immediate financial relief.

However, for anyone curious about what the wider community impact of mutual aid can be, she encourages them to visit the Vancouver Black Library and “take a look around and see if they are impressed with what a couple of e-transfers can do.”

“Even on a mutual aid call out that doesn't have a concrete physical example of what happens when you support in a small way,” says Preshyon, “it's often just as big and concrete and real as walking into this room and seeing everything that's here. Whatever's going on in every individual's life is just as big and real and important as something like this.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: