British Columbian voters don’t only get the chance to decide whether to stay with their current electoral system or move to one that produces more proportional representation in this fall’s referendum.

We also have the option of choosing which of three proportional representation options would produce the best results for voters in the province.

It can be complex, but in this series we’re cutting through the spin and explaining how each system would work, where it’s used and the advantages and weaknesses.

Yesterday, we looked at Dual Member Proportional.

Today, we’ll take a look at Mixed Member Proportional (MMP), already used in countries like Germany, New Zealand and Scotland. Of the three proportional systems on the ballot, MMP has the longest track record, having originated in Germany after the Second World War.

It’s called mixed member because it creates two types of MLAs.

The first would be elected locally using first-past-the-post in single-member districts — just as in the current system.

The second group of MLAs would be elected on a regional basis to ensure each party’s representation in the legislature reflected its share of the popular vote.

Mixed Member Proportional has been on the ballot before in both Ontario and P.E.I. In the 2007 Ontario referendum, 63 per cent of voters opted to stay with the current system. However, in the 2016 P.E.I. referendum, 52 per cent of voters supported a change to Mixed Member Proportional. The government didn’t act on the result, citing low voter turnout, but plans another referendum on the change in October 2019.

There is a lot of variability between Mixed Member Proportional systems, and the details of how it would work in B.C. would only be determined if the system is chosen in the referendum.

But there is enough information to show how the system could work in the province.

The government’s public engagement showed British Columbians don’t want to see a major increase in seats at the legislature. So we know that to free up space for regional representatives, the number of single-member electoral districts would have to be reduced, meaning ridings would be larger.

The government’s report on the referendum options recommended that at least 60 per cent of the legislature be filled with MLAs from single-member districts.

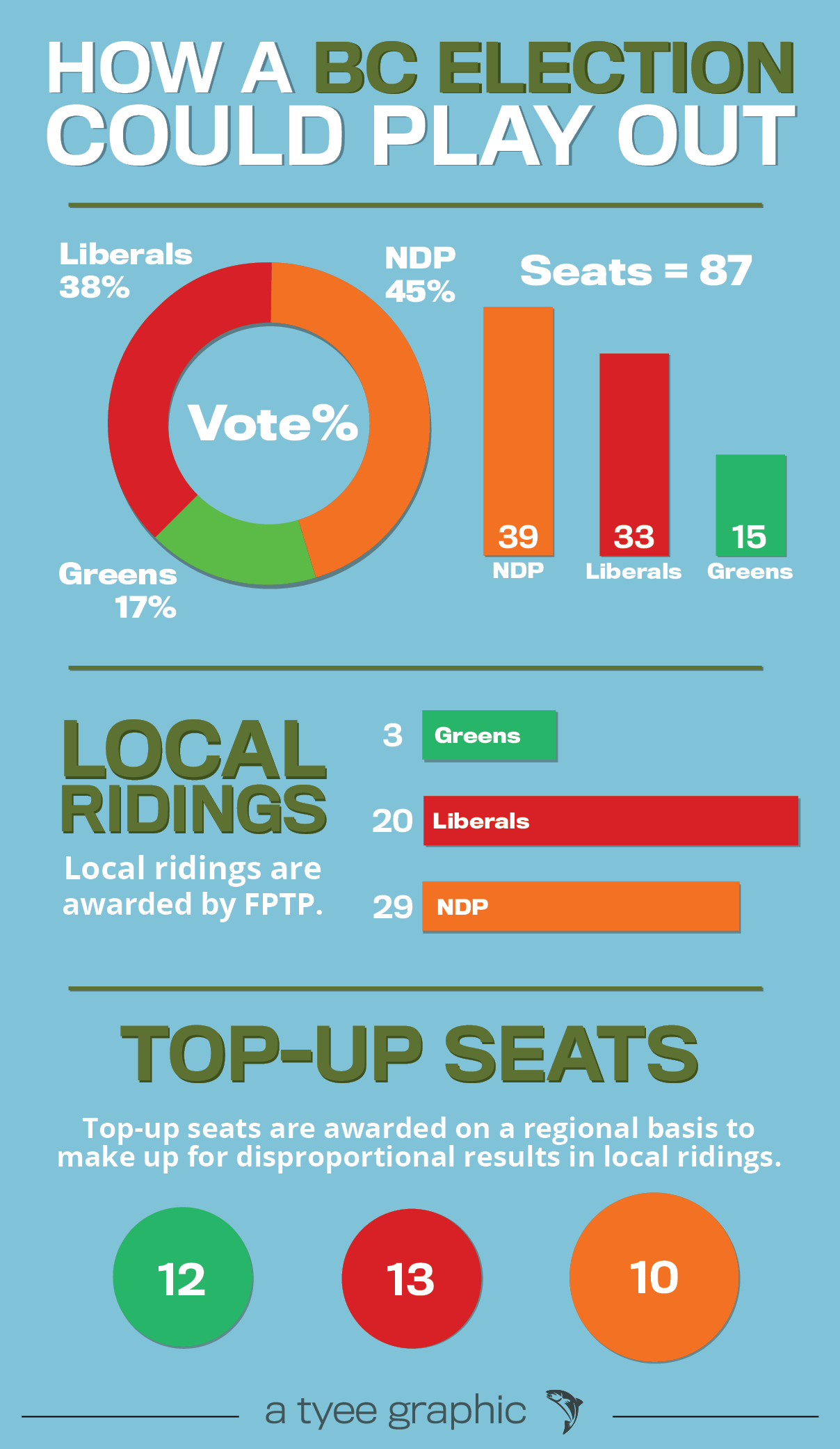

Using that information, we can project that 52 of the legislature’s current 87 seats would be occupied by MLAs elected under the current first-past-the-post system.

The remaining 35 would be divided among to-be-determined larger regions, such as Vancouver Island or northern B.C.

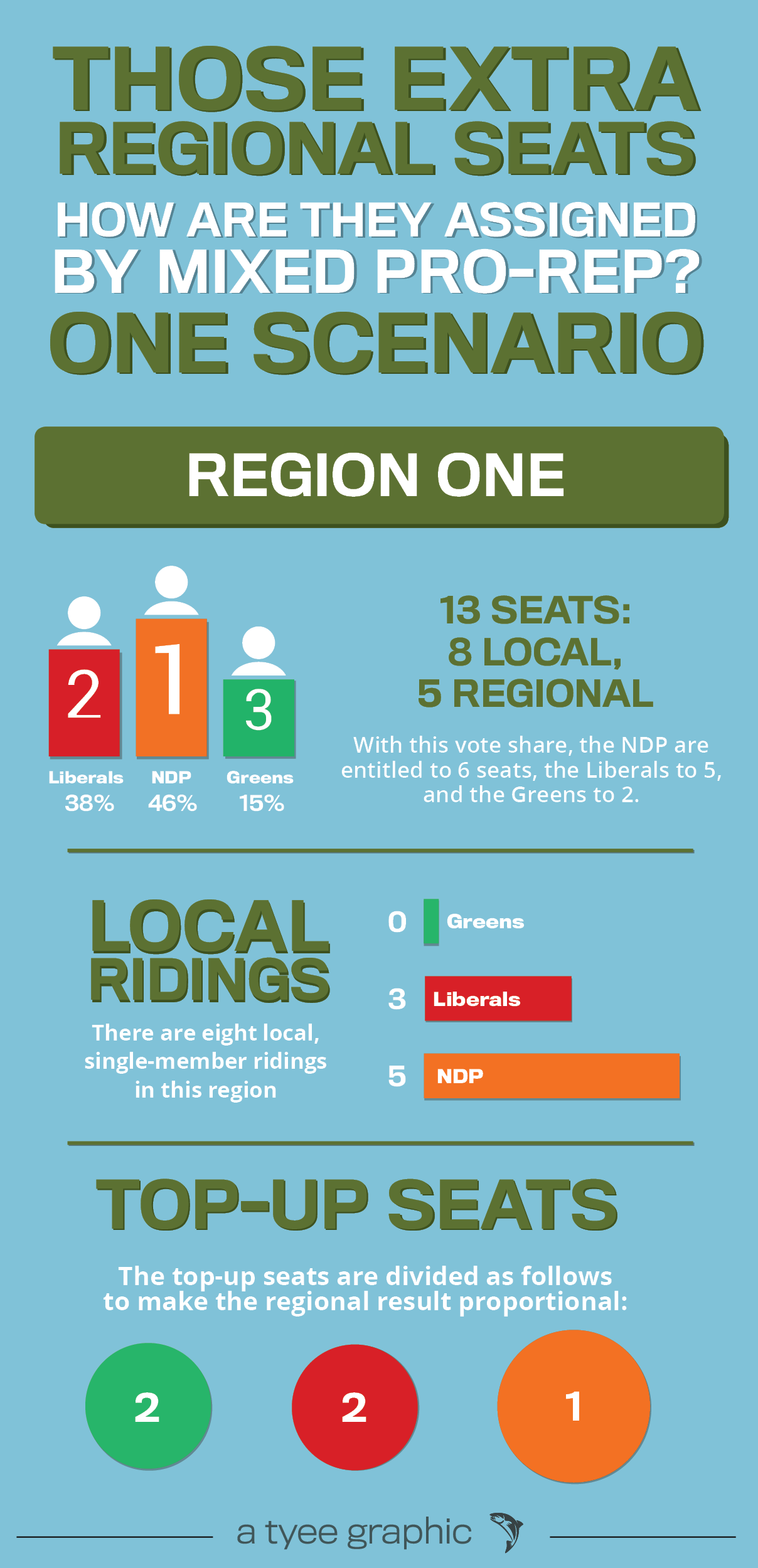

For example, there could be seven regions, each with five regional MLAs. So each citizen would be represented by a local MLA and several regional MLAs, likely from different parties.

A typical region might be made up of eight local ridings, each with its own MLA. There would also be five regional MLAs, elected based on the party vote and the need to ensure more proportional representation.

How does it work?

There are two options for electing the regional MLAs.

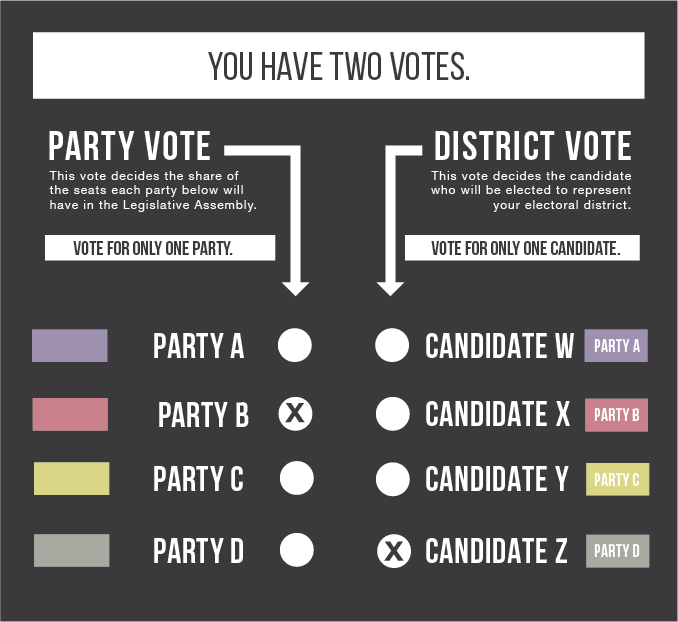

Typically, Mixed Member Proportional lets citizens cast two votes — one for their local MLA, and one for the party (and its list of candidates) at the regional level. This gives voters the ability to split their vote, supporting a local candidate from one party while voting regionally for a different party. But the government’s report on electoral options notes that the regional party vote could be established by totalling the votes from the local ridings in that region, in which case voters would only cast one ballot. That decision would be made after the referendum by an all-party commission.

The regional representatives would be elected based on support for each party, with the goal of achieving more proportional representation.

For example, if a party captured 25 per cent of the popular vote and elected 15 local MLAs, seven regional MLAs from that party would be elected to reflect the support. That would bring its representation to 22 seats — 25 per cent of an 87-seat legislature. (Only parties capturing more than five per cent of the vote across the province would be eligible for legislature seats.)

There are several options for deciding which regional MLAs are elected to produce proportional results.

They start with lists of candidates nominated or selected by the party.

In a “closed list” system, the parties decide which order their candidates will be listed on the ballot. The additional regional MLAs chosen to reflect the popular vote would be elected based on the party’s ranking.

In an “open list” system, each party lists its regional candidates on the ballot and voters decide which of them should fill the additional seats. That can be done by allowing them to vote for one candidate, or rank multiple candidates on the parties’ lists. (Voters could also have the option of simply selecting a party slate.)

David Moscrop, a political scientist at the University of Ottawa, says his preferred referendum option is Mixed Member Proportional.

“I think it maps pretty well onto British Columbia. It gives you a very clear local representative, and it makes sure that the fact that you have a local representative doesn’t render the rest of the results disproportionate,” said Moscrop. “It’s sort of the best of both worlds.”

But Moscrop said the other two proportional representation options would also be an improvement and would work in B.C.

“It’s really just a matter of what you want to highlight as a feature. I see that more as a matter of personal preference,” he said.

Proponents of proportional representation often claim it eliminates strategic voting, and that’s largely true. However, it can occur under Mixed Member Proportional.

For example, a voter’s preferred party might be hoping for support from a potential coalition partner. But the other party might not be sure of reaching the five-per-cent threshold required to win seats. It could make strategic sense to vote for the smaller party. Voters might choose to support a party they expect to play a key role in a coalition, rather than their first choice.

Under proportional representation, coalition governments would be the norm, something Moscrop said would improve our democracy.

“It tends to produce more co-operative and inclusive politics. That doesn’t mean that it ends partisanship and it shouldn’t. But it does tend to encourage and incentivize parties to work together,” he said.

The New Zealand experience

New Zealand made the switch from first-past-the-post to Mixed Member Proportional after a 1993 referendum, and backed the change in a second vote in 2011.

Under MMP, the number of parties represented in the House has increased. Under first-past-the-post, two or three parties typically won seats. The current parliament includes five parties; there were seven before the most recent election.

And results have become more proportional. In 1993, in the last election under first-past-the-post, the National Party took 51 per cent of the seats with 35 per cent of the vote. Three years later, under MMP, they won nearly the same portion of the vote, but dropped to 37 per cent of the seats.

In New Zealand, Mixed Member Proportional has also meant more Indigenous representation in Parliament.

Minister for Maori Development Nanaia Mahuta said that proportional representation has helped bring Indigenous issues to the table and improve diversity in politics.

New Zealand’s House of Representatives has had designated Maori seats since 1867. There are currently seven.

But Mahuta said the Maori are no longer dependent on reserved seats and have finally achieved a proportional level of representation, with Maori MPs in all but one party in Parliament. Maori make up about 15 per cent of New Zealand’s population.

“An MMP system with guaranteed Maori representation provides more support for issues regarding Indigenous people to be better worked through, because this is about collaboration. A coalition government is all about collaboration,” Mahuta said.

Governments need to do more to encourage political participation, Mahuta said.

“There needs to be public education, especially with Indigenous populations, to ensure that people participate in the political process,” she said.

“Letting Indigenous people feel disconnected from the democratic process… has affected the turnout but also our ability to connect with key population groups. Young people are a very strong example of where we’re failing to connect.”

One issue that did arise after New Zealand was about what should happen when an MP quit one party and joined another after being elected. It was especially critical for regional MPs, who were selected to ensure voters backing their party are fairly represented. If they cross to another party, it can upset the proportionality of the House.

A bill that would require MPs who leave their party to resign their seat is currently being discussed.

Moscrop isn’t in favour of this becoming law here, but still supports the principle.

“I would love to see a norm where a floor-cross would force an election in that riding. Not a law but a norm, because you are changing your relationship with that constituency,” he said.

For now, the focus should be on learning how proportional representation works and whether it’s right for B.C., he said.

Moscrop rejects claims the systems are too complicated for voters to understand.

“If you’ve ever learned how to drive a car, if you’ve ever learned how to file your taxes, these things are all more complicated than learning a couple electoral reform systems,” said Moscrop.

“We have the opportunity in British Columbia to something that very few jurisdictions get to do, which is to vote for our electoral system and choose it, and have the people choose it.” ![]()

Read more: BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: