British Columbians will soon face a major decision — stick with the current first-past-the-post electoral system, or move to a proportional representation system that ensures parties’ share of seats corresponds to their share of the vote.

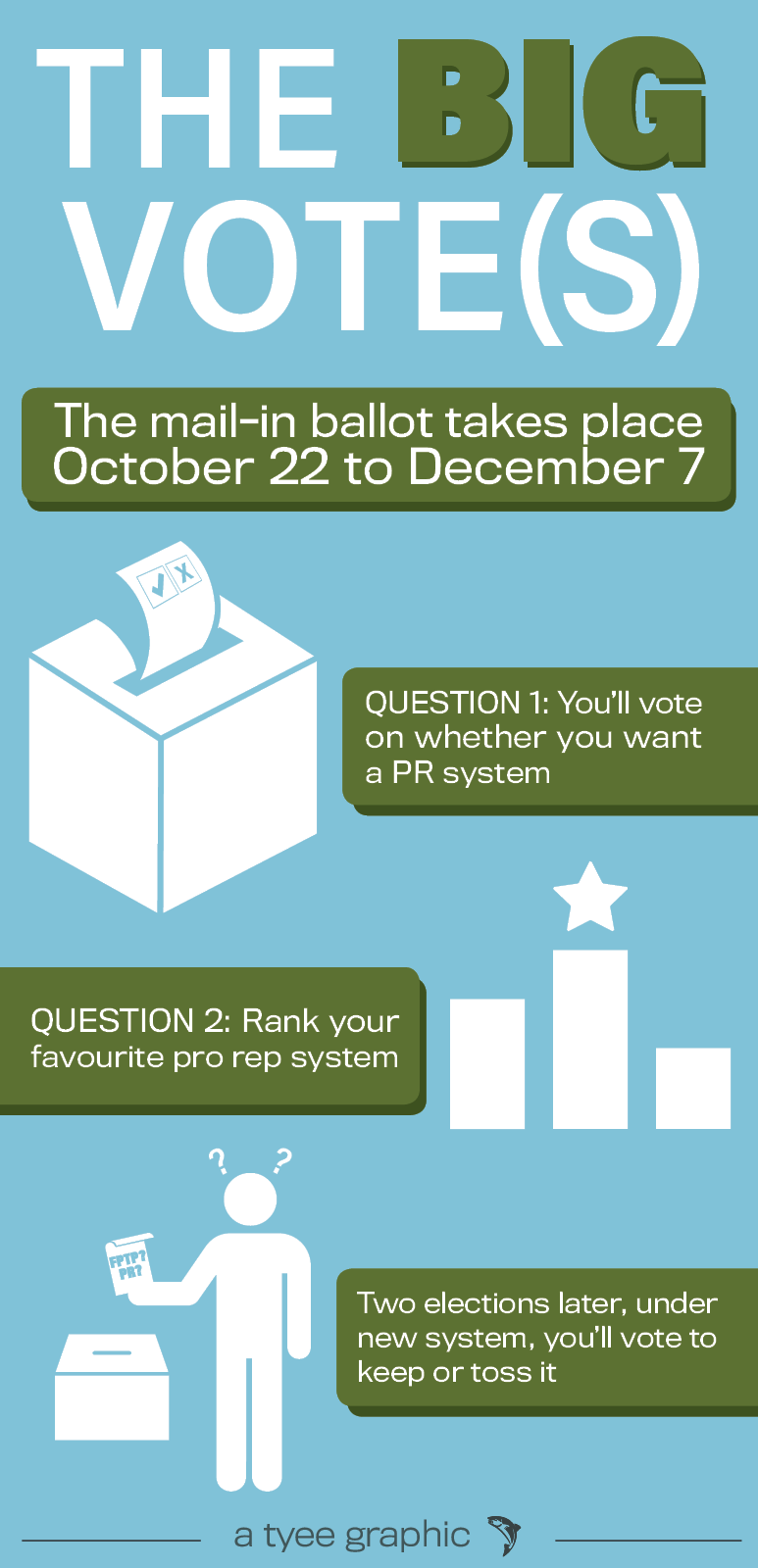

Both official sides will run fierce campaigns in the run-up to the mail-in ballot from Oct. 22 to Dec. 7, funded with $500,000 each from the government. Various other interest groups — each allowed to spend $200,000 — are also joining the debate. You’ll hear lots — but will you be able to trust it?

In this series, we’ll set out the facts about the options.

The referendum ballot will have two questions.

The first question will ask if voters support moving British Columbia to proportional representation or want to stay with the current first-past-the-post system.

The second question will allow voters to rank three proposed proportional representation systems. There is no requirement to answer both or rank all three systems.

Elections BC will count the ballots and first determine if there is majority support for proportional representation on question one.

If there is, Elections BC will tally the responses to the second question.

If one of the three options receives majority support, then the government will use that system in the next two elections. If all three options fall short, the least popular choice will be dropped and the second choices of the people who supported that option will be counted. That will produce a proportional representation option with majority support.

Even if voters support change, the government has committed to a referendum after two elections to see if British Columbians want to stay with the new system or go back to FPTP.

To cast a fully informed vote, citizens will need to know the basics of four electoral systems — our current one and three potential alternatives — and the pros and cons of each.

It’s a lot, we know. That’s why we’ve put together this series.

What is proportional representation?

The basic principle behind proportional representation is that a party’s share of the popular vote should be reflected in the number of seats it holds in the legislature. A party that receives 40 per cent of the vote should have 40 per cent of the seats in the legislature.

In contrast, the current system can produce variable results. In 1996, for example, the BC Liberals won the largest share of the popular vote. But the NDP, with less than 40 per cent of the votes, won 52 per cent of the seats. In this month’s Quebec election, the Coalition Avenir Québec was supported by 37 per cent of voters, but won 59 per cent of the seats.

But how would proportional representation work?

There’s no single answer, because proportional representation isn’t one system. More than 80 democracies use some form of proportional representation; just under 60 use first-past-the-post, the current system which awards a seat to the candidate who gets the most votes.

In the last two electoral referenda, British Columbians had a choice between FPTP and single-transferable vote, which is used at the national level in Ireland, Malta and Australia (for the Senate only), and at lower levels of government in many other countries. In the 2005 referendum, 58 per cent of voters wanted to change to the new system, short of the 60-per-cent approval threshold set by the government. In 2009, support fell to 39 per cent.

This time, three proportional systems will be on the ballot. We’ll examine each closely in coming articles in this series, but here’s a brief outline.

Dual Member Proportional would see most ridings have two MLAs. One would be elected using FPTP. The second would be selected based on the province-wide vote to ensure all parties had representation that reflected their share of the vote.

Under Mixed Member Proportional, MLAs would be elected in ridings that are larger than under the current system. Additional MLAs would be elected on a regional level — based on overall vote share — to make the final result proportional. We’ll look at how those MLAs would be chosen later in the series.

Under Rural-Urban Proportional Representation, urban ridings would elect up to seven MLAs using single-transferable vote.

Under the system, voters rank as many candidates they like and the results are based on their rankings. Advocates say this results in a legislature that more accurately reflects voters’ choices. Rural areas would use mixed member proportional, just as described in the paragraph above.

Each option retains FPTP to some degree, while adding other mechanisms to make the overall outcome proportional.

Attorney General David Eby led a four-month public consultation on proportional representation and the referendum, giving British Columbians a chance to share their opinions, expertise or concerns. Individuals and organizations also had the opportunity to submit proposals for systems to be included on the ballot.

“The problem that I faced, and it wasn’t one that I anticipated or our staff anticipated, was that there was not one clear favoured system when people participated in the engagement process,” said Eby. “The point of giving a choice of systems to British Columbians was to allow them to give government direction about where they wanted to go with the system.”

What did become clear, Eby said, was that the public wants an electoral system that is simple and produces proportional results, but not at the expense of local and rural representation.

It’s a tall order, especially considering the province’s vast geography and diverse communities. Each proposal balances these issues differently.

“Some systems reflect increased simplicity but reduced proportionality, and there are some systems that are more established and have a long track record of being used in other countries,” said Eby.

Others, he added, “are brand new, but are specifically designed to respond to Canadian geographic and demographic realities.”

One of three choices, mixed member proportional, has long been used in Germany, New Zealand and other democracies. The other two options on the ballot aren’t currently in use anywhere, although they are closely related to systems that were, or are, being used in other countries.

Each, in the form they would be implemented here, has been tailored to British Columbia and the needs and values of its population.

For example, British Columbians said in consultation that they don’t want a big increase from the current 87 MLAs. Typically, when a jurisdiction switches to proportional representation the number of seats increases to make it easier to have a proportional result.

British Columbia could see up to eight seats added under the three proportional representation systems. This is among the questions — including new electoral boundaries — that would be decided after the referendum if voters opt for change.

The government’s report says these “should be decided by a transparent multiparty process.”

Richard Johnston, a UBC political science professor and Canada Research Chair in Public Opinion, Elections, and Representation, believes this approach plays into the hands of those opposing proportional representation.

“By leaving so much to the post-referendum period, the government is inviting the opposition to impose every kind of demonic fantasy that they want on it,” he said. “They can just cherry pick all the bad examples from everywhere in the world and just impose them on the whole range of the alternatives.”

Indeed, the BC Liberals’ website cites several seemingly alarming examples. Under the heading, “Fringe Parties will hold the balance of power,” they write, “In Germany, far-right parties are no longer a thing of the past. In Israel, it’s nearly impossible to govern without granting concessions to a small but influential radical party.”

The German example refers to the rise of the Alternativ für Deutschland party. While certainly a party of the far right, AfD can hardly be considered a fringe party after having taken 12.6 per cent of the popular vote last year, winning 94 seats.

The party is not in the governing coalition and doesn’t hold the balance of power. But supporters of FPTP note that most of AfD’s seats came as a result of proportional representation measures. Despite receiving more than five million votes, the party only won a plurality in three constituencies. Their other 91 representatives were added based on party lists.

In the case of Israel, small parties often help coalitions reach a majority in the Knesset. However, Israel’s electoral system is known as party-list proportional representation and is not on the ballot in B.C.

Israeli voters only vote for the party of their choice, not representatives. The system awards seats to any party that receives at least 3.5 per cent of the countrywide votes. That’s allowed 10 parties to win seats in the current parliament.

By contrast, Germany and New Zealand have the same threshold proposed for B.C. — five per cent — and, respectively, have six and five parties represented at the national level, similar to Canada’s five parties.

Small parties can also hold the balance of power under FPTP. In B.C., the Greens could have helped either party form government after the 2017 election; they chose the NDP and that’s one of the reasons we’re having this referendum. New Brunswick’s election last month resulted in a similar outcome.

The U.K. Conservatives won a minority government under FPTP and now rely on the small Democratic Unionist Party from Northern Ireland to retain power. Many consider the DUP to have extremist views; they oppose same-sex marriage and abortion rights, and were previously affiliated with loyalist paramilitaries.

The BC Liberal Party, alongside the NDP and Greens, is one of 14 currently registered referendum advertising sponsors.

In short, the “No” campaign argues that our current system works perfectly well. They say proportional representation is too complicated for voters to understand and leads to unstable, minority governments and the loss of local representatives.

The “Yes” proponents argue that it isn’t fair for a minority of voters to elect a majority government with 100 per cent of the power. They believe proportional representation will bring a diversity of voices to the legislature, encourage parties to work together and result in more stable policies over time.

Who’s right? We’ll lay out the facts and examples from around the world in this series and let you decide. ![]()

Read more: BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: