[Editor’s note: To read the first part of this two-part series on raw log exports, go here.]

TimberWest has been the second largest exporter of raw logs from British Columbia for years. And a new move by the company has both forest industry workers and environmental activists convinced that it’s laying the groundwork for even more exports in the years to come.

Work under way at TimberWest’s pulp mill in Crofton, south of Nanaimo, is setting the stage for the company to load even more raw logs into the holds of ocean freighters, a move that will earn the company higher returns.

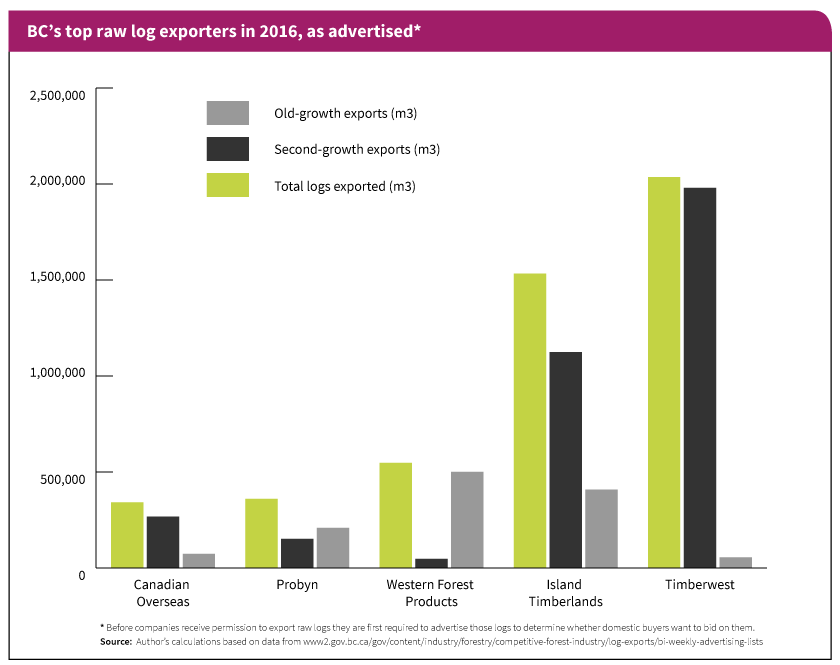

The company’s move to create what amounts to a new “value-added” raw log export facility comes when TimberWest and Island Timberlands are already B.C.’s undisputed log export powerhouses.

A database maintained by the provincial government shows the two companies accounted for more than 44 per cent of the nearly 8.1 million cubic metres of raw logs that logging companies hoped to ship from the province in 2016.

A major reason TimberWest and Island Timberlands exported roughly four times more logs than their nearest rivals is that both companies benefitted from past purchases of competitors that at one time owned large swaths of southern Vancouver Island forests. The companies owned those lands because of a deal struck in 1871 when British Columbia joined Canada as the sixth province. At that time, provincial lands were transferred to the federal government to clear the way for railway developments. The properties included a large chunk of forested land on southern Vancouver Island that came to be known as the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Land Grant.

As the decades passed, the lands were transferred to railway companies and then to timber companies. The forest companies coveted them for many reasons, but a few stand out.

First, the land was extremely good for growing trees, particularly the southern coastal forest’s iconic and valuable softwood species, Douglas fir.

Second, because the lands were not under provincial Crown control, no timber-cutting or stumpage fees applied to logging on them.

Third, as southern Vancouver Island became more urbanized, pushing property values up, the lands became attractive for subdivision and sale for potential housing developments.

Provincial data show that in 2016 Island Timberlands sought to export more than 1.3 million cubic metres of raw logs from private lands and TimberWest sought to export slightly more than 1.6 million cubic metres. Both companies also sought to export significant volumes of logs from Crown lands: TimberWest’s tally from those lands was more than 413,000 cubic metres and Island Timberlands was more than 202,000 cubic metres.

Log exports from Crown land have been increasing, with almost 60 per cent of the logs that companies sought to export in the past five years originating from public lands. Should the province’s two largest raw log exporters increase their log exports from Crown land log exports even modestly, the share of logs exported from public lands could quickly climb above 60 per cent.

The TimberWest example, in particular, is a cautionary tale of what may be ahead without changes in the way the provincial and federal governments regulate the booming log export industry.

The company’s latest venture at Crofton has flown largely under the radar. The plan is ingenious in its simplicity and does create a “value-added” product of a sort. A large area of land near an existing dock has been paved so that more raw logs can be delivered by truck. Each log will then be run through a “debarker,” which strips the outer layer of bark. The stripped logs are smaller in diameter, meaning many more can be loaded into the holds of ocean freighters. The smaller logs mean lower shipping costs per unit and higher profits. Hence the “value added” — but not in a way most advocates for sustainable forestry envision.

The Crofton pulp mill owned by Catalyst Paper will benefit, as the bark can be used as an energy source in the mill. But that is a far cry from what workers at Crofton and other pulp mills on B.C.’s coast really need — wood to make pulp and paper. Historically, the cheapest and best source of that wood was the leftover chips and sawdust produced when local sawmills processed logs.

Whenever round logs are processed into rectangular lumber a great deal of “waste” is generated in the form of chips and sawdust. That historically provided pulp and paper companies with the bulk of their raw material needs. But with so many of the province’s sawmills closing their doors in the past two decades, pulp mill operators have had to scramble to find the wood they need. In what amounts to a “value subtracted” approach, B.C.’s pulp companies are increasingly forced to buy whole logs to turn into chips in order to stay in business.

At Nanaimo’s Harmac pulp mill, not far from Crofton, the shortage of wood chips and sawdust from the remaining coastal sawmill industry is so acute the company is forced to buy and chip 600,000 cubic metres of logs annually. That’s enough logs to supply two new coastal sawmills, which could employ hundreds more forest industry workers. Those operations would, in turn, generate wood “waste” that could support yet more workers in the pulp and paper industry.

For decades, that was how business was done in B.C.’s forest industry. In fact, it was pretty much a requirement. Companies that logged some of the same Crown lands that TimberWest and Island Timberlands log today were granted long-term access to forest land by the provincial government on the explicit understanding they would run sawmills near their logging operations.

In 2003, the provincial government scrapped that requirement, which encouraged a sharp increase in raw log exports.

TimberWest’s role in the changes around that time is worth noting, particularly in light of the company’s efforts now under way at Crofton.

Crofton’s pulp mill was once owned by BC Forest Products (BCFP), then the second-largest forest company in the province next to MacMillan Bloedel (MacBlo). Both BCFP and MacBlo ran highly integrated forestry operations. The logs they cut were processed in their sawmills, the wood waste generated at their sawmills became the feedstock for their pulp mills.

Then corporations were taken over by larger multinationals, and in both cases the new owners decided to break up the assets they had purchased to focus on “core” areas of business. When New Zealand-based Fletcher Challenge was done dismantling BCFP, TimberWest emerged from the ashes to become essentially a “pure” logging company with a substantial side interest in real estate.

In January 2001, TimberWest closed the one manufacturing facility it had, the Youbou sawmill in the small Vancouver Island community of Lake Cowichan. With the closure, 220 men and women lost their jobs. At the time, 100,000 people worked in the province’s forest industry, about 40,000 more than today. The Crofton pulp mill was affected by the closure. The Youbou sawmill had been one of its major wood chip suppliers.

TimberWest, like other forest companies operating on B.C.’s coast, is now under no obligation to operate any mills, meaning there are virtually no hurdles in its path to exporting raw logs.

Under current rules, only logs deemed “surplus” to the needs of domestic sawmills can be exported. Exporting logs cut on Crown lands requires payment of a “fee in lieu” of manufacturing to the province.

The enormous volume of logs exported by TimberWest indicates that it is exporting logs both from lands it owns outright and from Crown lands, including from the company’s Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 47. TFL 47 was once one of those licences that required the holder to operate mills. But that rule no longer applies.

TFL 47 also has the distinction of including lands at the southern end of the Great Bear Rainforest, where for a number of years TimberWest has been in conflict with Sonora Island residents and others who have fought the company’s ongoing and proposed logging of centuries-old Douglas fir and Western red cedar trees.

One aspect of the dispute, as first reported by The Tyee’s Andrew Nikiforuk, is whether TimberWest’s definition of “second growth” forests includes forests that may actually contain increasingly rare and valuable old-growth trees.

In an effort to quantify where raw logs exported from the province originate, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives filed a Freedom of Information request with the provincial ministry of forests lands and natural resource operations. The request was for a list of all “timber marks” associated with logs linked to export shipments.

The ministry refused to release the information. The CCPA is challenging the decision and has filed a request for review with the provincial Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner.

Regardless of whether the provincial government eventually releases the timber mark data, a disturbing reality remains. For more than a decade the government has allowed more and more trees from lands under its control to be exported without ever being run through a mill and turned into any one of a number of forest products. The manufacturing of those products historically provided thousands of British Columbians with good-paying jobs that have been the economic backbone of many of the province’s rural communities.

Under existing rules, there is nothing stopping companies that own and operate mills in the province from doing exactly what TimberWest has done, which is to close mills and put hundreds and conceivably thousands more people out of work.

Barring a change in approach, today’s log exports may very quickly be overshadowed by those of tomorrow.

To read the first part of this two-part series, go here. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, BC Election 2017, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: