[Editor’s note: This is the second-last instalment of a six-part series exploring life and risk on the Lower Mainland’s floodplain, the stretches of flat land in the region between the Fraser River and the coast. If you haven’t read it yet, we invite you to read the first four stories that ran earlier this week.]

Climate change is already on the doorstep of the Musqueam First Nation.

January saw one of the highest king tides in recent years, according to the federal hydrographic service, at 5.48 metres. Waves crashed at the edge of Musqueam’s low-lying reserve, which is on raised land along the banks of the Fraser River, nearly swallowing the community’s boat ramp.

A river flood during freshet isn’t as big of a danger here because this is the mouth of the river where it meets the Salish Sea, says Norman Point, who manages the band’s public works department. Instead, he worries about coastal floods as the sea level rises, and the potential of a future “perfect storm.”

“If it’s accompanied by a lot of rain and wind — that’s not a good thing,” he said.

Tides might have nothing to do with climate change, but winter storms do. They’re getting stronger, and if a storm shows up at the same time as a winter tide, shorelines are in for heavy damage.

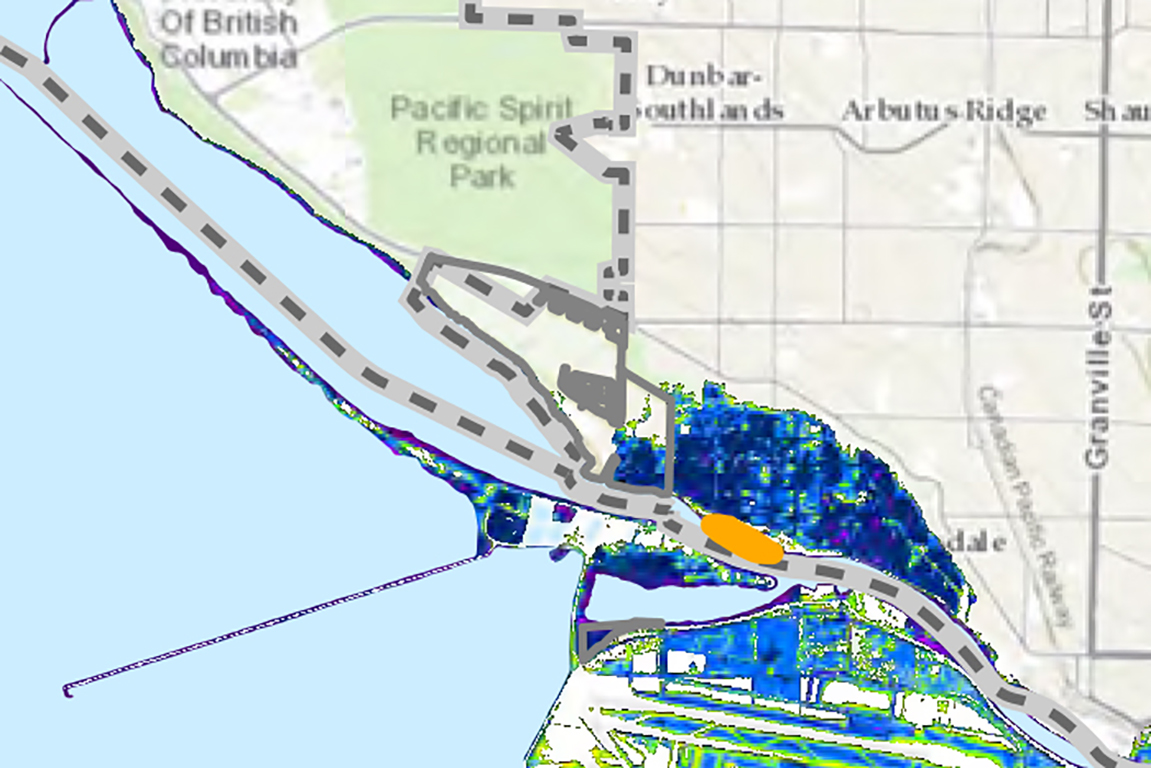

Norman, 60, and his brother Ricky, 59, who also works in the public works department, have always lived on the reserve. It’s located near Vancouver’s southwest, nestled among farms, mega-mansions and golf courses at the edge of the city’s Dunbar-Southlands neighbourhood. Even before colonization, this spot at the mouth of the Fraser River, where it meets the Salish Sea, was always home to the Musqueam people’s main winter village.

Living so close to the water meant that flooding has always been top of mind.

“My grandfather, he had a boat tied up to his back porch,” said Ricky. “His home was on stilts. So that’s how they dealt with it back then. My dad used to tell us that in the winter, they had to get in it and paddle up to 51st, [the avenue that leads to Vancouver], because the water went all the way up there.”

Since the 1970s, houses on the reserve were built on concrete slab foundations. Houses do not have basements, because they would be prone to flooding.

“If you dig a hole a few feet deep during high tide, you’ll find water,” said Ricky.

With climate change, one metre of sea level rise is expected by 2100. A flood mitigation study for the reserve is in the works, due to be completed in the fall. Band members will review and give feedback after that.

It’s a “sensitive” issue for members because big changes are on the table, says Norman.

“It’s not an easy task at all,” said Norman. “Do we retreat? Start building in another area and move all the homes? Or do we raise them? What’s practical? Obviously, along with that comes a lot of expenses. There are still impacts to the community, no matter which option you choose.”

For example, if the band were to surround the reserve with dikes and superdikes — like the City of Richmond does — that would restrict important access to the river.

The Musqueam, a hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓-speaking people, used to have camps and villages all over the region for thousands of years before colonization. After the Indian Act, they were forced onto a small fraction of their original territory. The majority of the reserve is leased to other parties — which have expiry dates between 2032 and 2073 — resulting in a community that’s currently about 65 hectares in size. About 1,300 of their members live on the reserve, with a waitlist of over 300.

As the sea rises, it’s even less land for the Musqueam to work with.

‘Landlocked’

It’s not the only First Nation with a reserve in a flood zone.

In the Lower Mainland, there are 61 reserves belonging to 26 First Nations that are vulnerable to floods, according to the Fraser Basin Council.

For the Kwantlen Nation, for example, it’s an existential crisis. McMillan Island, which they call home, is expected to be underwater by 2100. In 2012, floodwaters came for their band office, filling their basement and boardroom. But members don’t want to leave their home.

“For a lot of us, we became landlocked next to the Fraser when the reserve commissioners came along,” said Tyrone McNeil, chief of the Stó꞉lō Tribal Council and a member of the Seabird Island Band near Agassiz.

“In a hundred years, we’re going to lose a lot of reserve land because it’s either going to be underwater or simply too expensive to protect.... We need new additions to reserves away from the river, out of the floodplain. We’re not going to walk away from our lands and step onto fee-simple lands.”

In his many years holding a variety of leadership positions, McNeil has come to see that the way Fraser River communities deal with flooding is too “piecemeal.”

“Historically, all we’ve had is local governments and First Nations competing for inadequate funds that are proposal based. One year you get funded, the next year you don’t. It’s so ad hoc in nature. It’s not strategic. If I put a dike [in one community], what does it mean downriver? It doesn’t account for those impacts.”

The sentiment is shared by other local leaders, who say that grants from senior governments don’t often go to the jurisdictions in the most need. Applying for them is also expensive, especially for smaller governments.

It’s even tougher for First Nations to fund flood solutions because they don’t have the tax base that local governments do. The Katzie First Nation, for example, relied on volunteers building sandbag barriers to keep the rising Fraser at bay back in 2018.

McNeil chairs a new group called the Emergency Planning Secretariat, founded in 2019, to advocate for the 31 First Nations by the Fraser River. They’ve been meeting with First Nations communities as well as senior levels of government and are in the process of becoming a non-profit society. His hope is for the Coast Salish-led EPS to create a co-ordinated flood management strategy recognized by the provincial and federal governments.

“There are really hard decisions to be made,” said McNeil. “But who better to make them than those of us who are directly impacted?”

‘What colonization has done’

“If you go back 200 years ago, there’s no such thing as an industry called logging,” said McNeil. “It would take anywhere from three months to six months for rain that’s hitting the top of the mountain to make its way into the river. You’ve got huge spans of trees. You’ve got all kinds of vegetation and everything under it. It will just be absorbed, and release the water slowly.”

A 2021 study of the Lower Fraser found that only 101 out of an estimated 659 square kilometres of historic floodplain and salmon habitat remain today, lost with urbanization.

As a result, water comes down the Fraser more powerfully than it did in the past, says McNeil.

“With climate change, that’s just going to add to the volume and speed of water coming down the tributaries, dragging down all the gravel and rock.... That’s what colonization has done.”

On top of that, Indigenous peoples can’t depend on the Fraser for their livelihoods in the same way anymore.

McNeil worries that the road to 2100 will be business as usual. In other words, ignoring what the Fraser is trying to teach us.

Should a dike really be located where it is? Does it need to be set back? Should old waterways be reopened to help divert and absorb floodwaters? He hopes communities in the floodplain will ask these questions rather than just want more and bigger dikes.

“Imagine the volume of water that could be absorbed if we open up half of those lost waterways! No worry about freshet anymore. The beauty is, when we do that, we’re restoring and reclaiming fish and salmon habitat.”

Climate change clues

On a rainy spring day, the Point brothers are out for a stroll on the reserve down Salish Drive.

Ricky recalls the storm surge of 2015, the region’s worst in 50 years. Thankfully, the waters receded. But then there was the atmospheric river last November, which brought the heavy rainfall that caused the devastating Sumas Prairie flood. Ten houses on the reserve flooded.

The brothers stroll past the Musqueam Golf Course, which is owned by the band, where water is pooling on the greenway. It’s next to the residential part of the reserve, which is elevated, but the golf course is not. This makes it prone to flooding, especially in the winter, says Norman.

Living on low-lying lands by the river, there are a lot of hints that climate change isn’t a matter of “soon,” he said.

“We can see it now.”

On Monday, in our sixth and final instalment of this series: What will it look like when a flood hits, and what will it take to protect the Lower Mainland? ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Municipal Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: