[Editor’s note: This is the fourth instalment of a six-part series exploring life and risk on the Lower Mainland’s floodplain, the stretches of flat land in the region between the Fraser River and the coast. If you haven’t read it yet, we invite you to read the first half of the series that ran earlier this week.]

Kevin Severinski remembers his uncles talking about the “Big Flood” of 1948 that covered the Pitt Meadows family dairy farm in a foot of water. An unusually hot spring and heavy rainfall created a freshet flood that swept across 12,500 hectares of the Lower Mainland, forcing the evacuation of 16,000 people and damaging 2,300 homes.

But on the Severinski Farm, the damage was minimal thanks to foresight by Kevin’s grandfather, Steven Severinski. When Steven bought the farm in 1921, the main house sat next to the Alouette River — which was handy for a family of 12 that had to drink, cook and clean with water from the river, Kevin says. But after a small flood, Steven put the house on logs and dragged it to the highest point on the property about a metre higher and half a kilometre away from the river.

The new location created a longer distance to have to haul water, but it meant the house stayed dry during 1948 when the fields and barns flooded, Kevin says. His uncles stayed elsewhere during the flood but would ride horses or drive into the farm daily to feed and milk the cows, who stayed on the farm because there were still dry places they could rest.

“Back in the day you built on the high spot, everyone knew you were in the floodplain,” he says.

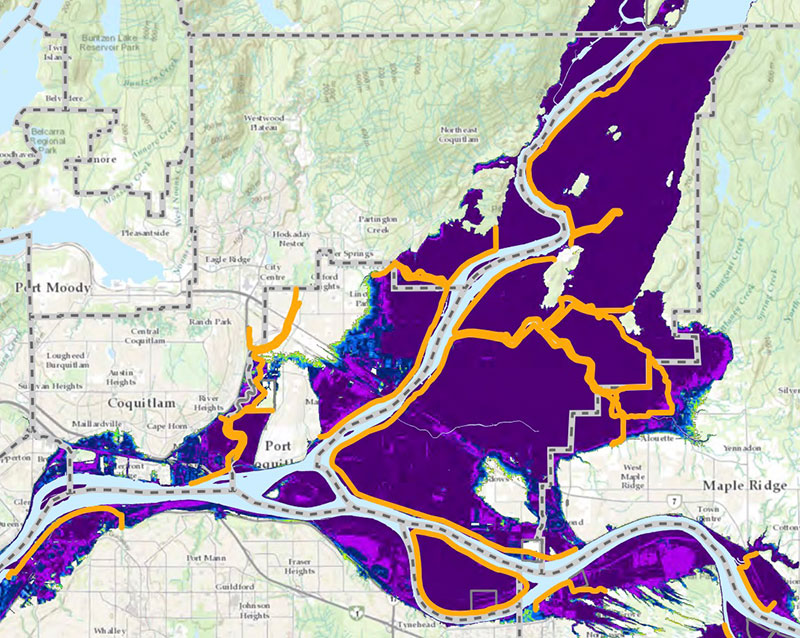

This is especially true in the small municipality of Pitt Meadows, where 86 per cent of the community sits in a floodplain and “flooding can happen at anytime” due to heavy rain, rain on snow, spring freshet and mechanical failure of pump stations, according to the city’s website.

The city’s 19,146 residents are protected by 60 kilometres of dikes, six pump stations that drain four regions, 177 kilometres of ditches and 736 culverts that keep the Fraser, Pitt and Alouette rivers out. While the municipality doesn’t touch the Pacific Ocean, the community feels the push and pull of the twice-daily tides that swell and shrink the rivers.

Freshet season, from May to June, is when the community is at highest risk of flooding because that’s when rivers swell. But climate change, and the resulting atmospheric rivers like the one that washed through southern B.C. in November 2021, is changing the rules, says Barbara Morgan, manager of Pitt Meadows’ emergency program.

Flood mitigation infrastructure is built to withstand historic floods. Municipalities look at what sort of floods washed through the Lower Mainland in the past and use that as a base to understand what sort of threats the community will face in the future. But climate change shifts when, where and how extreme weather hits, which means historic flood data is less reliable when it comes to predicting future flooding events.

Think about how the Coquihalla Highway was washed away during November’s atmospheric river. The road would have been built to withstand extreme weather that has rolled through B.C. before — but its designers didn’t plan for an atmospheric river. What other kind of extreme weather might be just around the river bend that we haven’t planned for?

Despite the high risk, the community deals with very few localized floods, Morgan says — usually just the pooling of rainwater, also known as overland flooding.

But when it comes to flooding, historic success doesn’t guarantee future wins. The Lower Mainland sits on a floodplain so we know floods are, so to speak, coming down the pipes — it’s just a matter of when.

And as the Fraser Basin Council’s Steve Litke mentioned in this series’ article about Delta, “the Lower Mainland’s diking system hasn’t failed significantly, but it also hasn’t been tested significantly.”

Small municipality, small budget

It’s not the old houses that get flooded, Severinski says, but the new homes built in the last 15 years on “nice clear low” spots. They seem appealing to those unfamiliar with the region because the land is level and free of trees — perfect for rolling some construction vehicles in and getting to work building a house. But there’s a reason those spots have been left undeveloped for the last 100 years.

Development also plays into overland flooding, he adds. If 75 millilitres of rain falls on 100 hectares of grassland, the earth will absorb the water. If the same amount of rain hits asphalt and new development, the water will flow to the community’s ditches.

Ditches intersect the city, sometimes following roads or winding their way through fields, and help collect water to be pumped out using Pitt Meadows’ six pump stations, Morgan says. Some can hold half a metre of water, and others, you could tread water in when they’re full.

The city is also constantly upgrading its infrastructure and recently finished adding a backup generator to its fifth pump station. The upgrades bring the five pump stations up to current provincial standards and will allow fish to pass through the waterways.

But climate change and sea level rise means municipalities can’t just maintain infrastructure — they have to upgrade it. The city’s flood mitigation plan, which plans for one metre of sea level rise predicted for the year 2100, estimates improving dikes and pump stations will cost between $135 million to $121 million.

Therein lies the rub: Pitt Meadows is a very small municipality (with a population under 20,000) so its tax base is several times smaller than surrounding municipalities (for example Surrey, with a population of over 568,300) but it has to maintain the same amount of infrastructure.

The city “does as much as we can,” Morgan says, “but dikes cost millions of dollars.”

To pay for these projects, the municipality relies on grant funding through the Union of BC Municipalities and senior levels of government.

Adapting the community to be climate-change resilient, which includes building taller and wider dikes, “will take many years,” Samantha Maki, director of engineering and operations, told The Tyee in an email. It “depends on available funding from other levels of government as well as city reserves.”

Pitt Meadows is also working with the Fraser Basin Council as part of its Lower Mainland Flood Management Strategy, “which is focused on developing a long-term plan for flood mitigation, regional priorities and funding options,” Maki says. The city “continues to advocate for a dedicated funding stream to support the necessary improvements to flood infrastructure.”

The city’s flood mitigation plan includes a “prioritization map” to guide what upgrades come next, she added.

The city does not distinguish between urban and rural populations for flood protection — it just looks at the weakest spot and fixes that next, Morgan says.

The city also has resources for potential homebuyers, and Morgan says she is always happy to help people interpret municipal flood risk maps.

These maps could also help people new to the area avoid building homes or developments in high-risk flood areas. As Severinski noted earlier, there is usually a reason a nice, clear, flat piece of land has been left undeveloped in a floodplain.

'Is our diking system good? Yes!'

Despite these steps in the right direction, the community still has a risk of flooding. Pitt Meadows dikes sit around 5.4 metres high, which wouldn’t keep floodwaters out if the 1894 flood happened again.

Climate change is shifting when and how flooding events happen, says Litke, director of water programs at the Fraser Basin Council. In the future, freshet season might have more rain but less snow melt, and could happen in the middle of winter, coinciding with storm surges that swell sea levels. Storm surges are more common but less severe than freshet flooding that overtops dikes or dike breaches, but can damage agricultural land with salty water.

There’s also the small problem that all dikes come with the risk of failure during a flooding event, and can encourage development in flood-prone areas, notes a 2021 report from the Fraser Basin Council.

Kevin Severinski has watched the dikes get bigger over his lifetime. As a kid in the ‘70s, the water was always half a metre from the top of the dike, he says. He used to sit on his patio and watch water skiers go by on Alouette River. Because the water was so high it looked like they were skiing along the top of the dike, he says.

Now, he says, the top of the dike stands five metres above the water level. Plus, the daily tides means the water can drop a couple metres in a day, he says.

This speaks to the work municipalities all across the Lower Mainland have done to protect their communities from flooding for generations. This infrastructure is usually hidden in plain sight — a maintained ditch winding alongside a road, or a walking path that runs along the top of a dike. Unless you’re looking for it, you might not notice it. Municipalities are aware of flooding risks. The problem is that municipal funds are a zero-sum game: when you use money to build a pump station you take it away from other programs, like child care or hospitals. And because the Lower Mainland hasn’t faced an extreme flooding threat in over 70 years, it’s hardly front-of-mind for taxpayers and politicians.

Another problem is that when it comes to floods, a rising tide does not lift all boats. Instead, it seeps into communities through cracks and gets everyone’s feet wet.

The Lower Mainland’s flood mitigation infrastructure has successfully protected the region since the 1948 flood. But experts say the region isn’t prepared for the next flood, which is guaranteed to show up someday in the future. That is, afterall, the nature of a floodplain.

Litke, speaking to the Lower Mainland as a whole, said a large earthquake could damage dikes. Shaking could make the dikes settle up to 30 centimetres in some places, he says.

When asked how an earthquake could impact Pitt Meadows’ dikes, Morgan says it’d be hard to speculate.

“We wouldn’t really know what an earthquake’s impacts would be until it hit us,” she said. “Is our diking system good? Yes! But you don’t know what mother nature has got in the pipes until it comes.”

Next in the series: the Musqueam First Nation is landlocked in a flood zone — one of the impacts of colonization. ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: