[Editor’s note: We’re halfway through a six-part series exploring life and risk on the Lower Mainland’s floodplain, the stretches of flat land in the region between the Fraser River and the coast. If you haven’t read it yet, we invite you to read the first two parts of the series that ran earlier this week.]

Richmond is in a race against the rising tide.

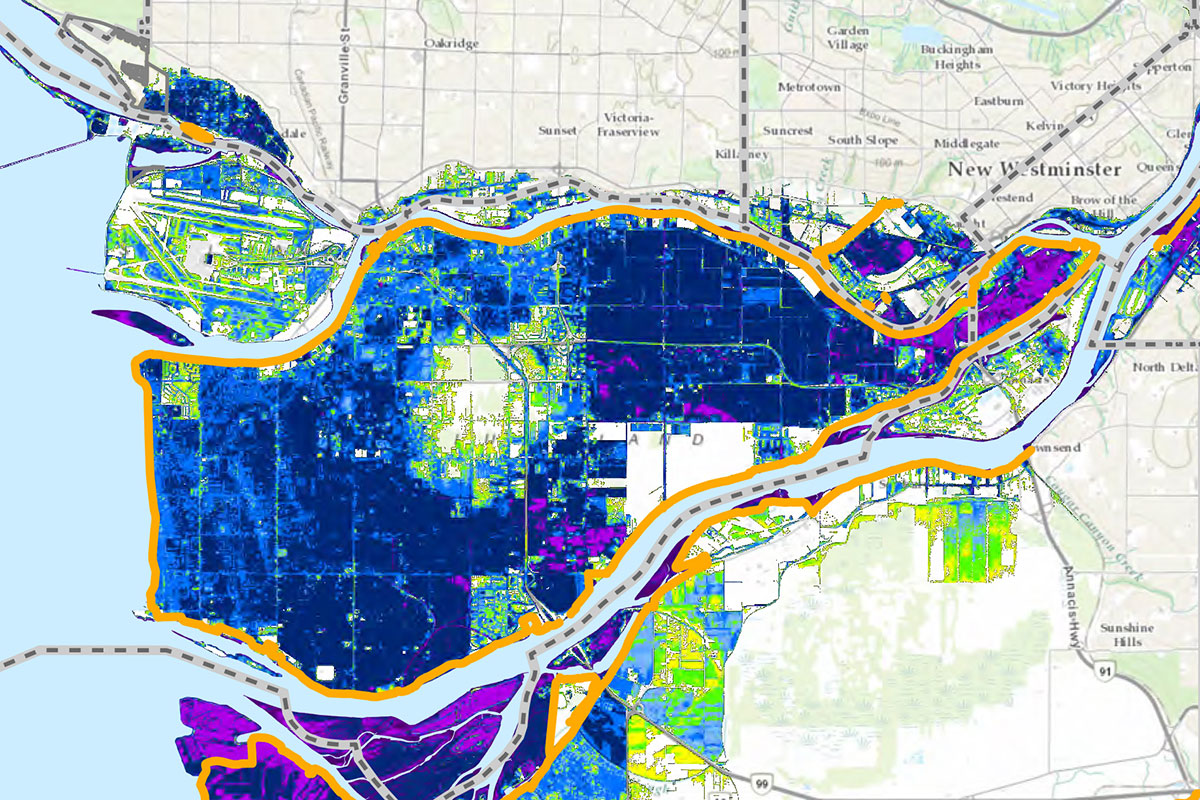

The island city, just south of Vancouver, sits at the mouth of the Fraser River and is, on average, one metre above sea level. That happens to be the height that the sea level is expected to rise by 2100. There’s also the issue of Richmond’s subsidence. In short, the city is sinking. By 2100, Richmond’s land will have dropped by 20 centimetres.

Every centimetre is essential as climate change worsens. Richmond is exposed to major floods on two fronts: by the coast and by the river.

Aside from the city’s need to protect 210,000 residents, crucial regional infrastructure is also at risk. Richmond is home to the region’s international airport, over 7,700 acres of farmland and key highways that lead to the Tsawwassen ferry terminal and across the Washington border. Plus over 7,700 acres of farmland.

Richmond is also notably the North American city with the largest percentage of Chinese residents, a population that took off in the 1980s as Hong Kong’s 1997 handover approached. A major flood would deal a devastating blow — culturally, economically, socially and more — to the region’s Chinese diasporas. The city is home to numerous Chinese churches and temples, warehouses that ship pan-Asian goods to supermarkets across the region and multilingual malls of offices, medical clinics and shops.

On a spring afternoon, Jason Ho is standing on Richmond’s first line of defense against floods. He’s just outside of Steveston, home to the city’s historic port and canneries. There’s a path here that runs along the Fraser River. It’s as busy as Vancouver’s seawall on this weekday, with joggers, bikers and dog walkers taking in the sun.

If you’re on a stroll or sitting at one of the picnic tables here, you might not notice that you’re on top of an important piece of infrastructure.

This is the great wall of Richmond, built to keep surging water away from the island city. Officially, it’s called a perimeter dike, forming a ring around Lulu Island, the main island on which Richmond is situated. The dike is the shape of a trapezoid, with sloped edges and a flat top, which ranges from 20 to 30 feet across. With roads and recreational goodies like trails and benches right on it, the dike is well-disguised.

Ho grew up in Richmond and, like many other residents, spent time walking and biking on the perimeter dike, which in the west has beautiful views of the sun setting over the water. “But you never think of it as a kind of flood protection asset,” he said.

That changed when he started working for Richmond’s engineering department. He’s since become the department’s manager, and knows exactly what’s in the city’s arsenal by heart.

“Forty-nine kilometres of dikes, 39 pump stations, over 500 kilometres of drainage ways,” Ho recites by heart like a nursery rhyme.

But is that enough to combat the increase and intensification of floods with climate change?

‘Child of the Fraser’

The fact that Richmond exists at all is thanks to feats of engineering.

“Richmond is pretty flat,” says Ho. “Without the dikes, when the high tides come in and there’s storm surge, parts of the island would be underwater.” Freshet is also a threat.

On the city’s coat of arms are the words “Child of the Fraser.” It’s a poetic nod to how the islands that make up Richmond were formed.

The city’s location, where the Fraser River met the Salish Sea, was once shallow open water. About 9,500 years ago, the river began depositing silt. Then some 3,500 years ago, that silt was shaped into islands by the tides.

The landscape was fertile, with bogs, grasslands and spruce forests. According to an archeological report by the city’s museum, Indigenous families — mostly from Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Kwantlen and from as far as Cowichan, Nanaimo and Saanich — had the right to the resources on the young delta islands. In late summer, this was one of the most populated places on the coast when salmon were plentiful. When winter arrived, people left their camps and returned to their communities.

In the 1860s, Richmond’s first European newcomers eyed the area for farms, but noticed that the land was saturated with water and needed to be drained. So the farmers dug ditches by hand and used the material they unearthed to build the community’s first dikes.

Fast forward to the present and Richmond has become the Lower Mainland city with the most extensive dikes and other flood protection infrastructure.

But can the city keep up with the conditions expected in 2100?

Richmond estimates that the price tag of fortifying its dikes to meet that one metre of sea level rise will be at least $1 billion.

From dikes to superdikes

Ho will never forget what a former boss told him: “No dikes, no Richmond.”

It’s not hard to imagine this when you’re standing on the south dike. On one side of the wall are houses, farms and warehouses. On the other is the Fraser River.

The side facing the water is fronted by giant boulders called “riprap.” Again, you might not notice that these boulders were placed there for a practical purpose because people enjoy them recreationally. Kids like to climb on them and they’re a good seat for fishers in waiting.

“The river moves pretty fast,” said Ho. “Without these rocks, over time, the velocity will slowly wear away at the dike. So the rocks protect the dike.”

Aside from Lulu Island, Richmond is also home to Sea Island, where the YVR airport is located. It also has a perimeter dike.

To meet the net sea level rise of 1.2 metres, existing dikes on both Lulu and Sea Island are being raised to 4.7 metres. New dikes are being built to 5.5 metres.

Last year, Richmond’s council decided to speed up the timeline for meeting these heights from 75 to 50 years, said Ho, which puts completion in the early 2070s.

The city has also been working with developers to build up its defenses. Dikes have enabled developers to build hot waterfront property, in some cases, right up to the dikes themselves. For over a decade, the city found a way to use this to its advantage.

Enter the superdikes.

Like dikes, they’re just as inconspicuous. When a new building goes up by the water, it’s built on elevated land; this is the superdike. One early example of this was the city’s Olympic Oval. As more buildings go up along the water’s edge, more land gets elevated, extending the superdike.

Developers are usually happy to build superdikes voluntarily: anyone buying a “ground-level” condo on raised land will enjoy a view of the water that isn’t blocked by Richmond’s great wall.

From ditches to drain pumps

It’s not just stormy coasts and surging rivers that Richmond has to watch out for. With the city so close to sea level and in such a rainy climate, water has to be drained from the land. That’s where ditches come in.

Like Ho, Susan Anderson grew up in Richmond without a clue about its low-lying landscape.

She was raised on Mowbray Road in the 1960s, where there were ditches instead of sidewalks at the edges of people’s front yards, running parallel to the road. This is typical of residential Richmond, and properties have little bridged driveways for people and cars to get over the ditches, which were a few feet wide and deep.

When she was six-years-old, she fell into one.

“In a weird way, they were our playground,” said Anderson.

The ditches offered different delights in different seasons. In the winter, Anderson and the neighbourhood kids would slide on the frozen ditch water with their winter boots. Her sister still has the scar from the year she slipped. In the summer, they nailed old coffee cans to two-by-fours and used them to catch tadpoles in the bulrushes.

One Sunday, on her way home from the local Baptist church, Anderson spotted a broom stuck in the middle of a ditch. Kids loved to pole vault across ditches, and there was an Olympic challenge on this particular day: the ditch was filled with mud.

“I thought I’d just do one quick hop before I headed home,” said Anderson. “I managed to leap, but to my horror, I discovered that the mud got too hard and thick and I got stuck midway. I slid right down into the muck! Just think of a little kid, with her church clothes and shoes and hat and all that, pulling on the grass to get back up.”

The moment she got home, it was into a mustard bath — her grandmother’s recommendation.

It wasn’t until later in life that Anderson learned about the role of ditches.

Rainwater collects in Richmond’s network of open ditches and other watercourses. Both rainwater and groundwater are then pumped into the sea and river by the 39 stations at the city’s edges.

At maximum, the stations can discharge 1.4 million gallons per minute, more than the capacity of two Olympic swimming pools.

No retreat for Richmond

In part one, we mentioned that Canadian flood experts have come up with the PARA framework to categorize solutions.

There’s the “protect” approach, which includes building up infrastructure like dikes; the “accommodate” approach, which aims to keep assets dry when flooding occurs with strategies like elevating or flood-proofing infrastructure; the “retreat” approach, to relocate important infrastructure in flood zones; and the “avoid” approach, refraining from building in at-risk areas in the first place.

“Traditionally in Canada and much of the western world… we’ve really focused and stuck on the hazard side of the story,” said Tamsin Lyle, an engineer and flood management expert at Ebbwater Consulting. “So doing everything in our power to stop the water from interacting with the things we care about.”

Because Richmond has relied on its dikes even before its inception, city staff and leaders are “locked in to the choices they made, and are continuing to buckle down building up the dikes and maintaining those dikes,” she said. “They haven’t got the same options as other places in terms of adjusting their land use.”

Richmond might be focused on the “protect” approach now, but Ho at the city did mention a goal of raising an entire island in the long term, which would take infrastructure “out of the floodplain altogether.”

There’s another reality of being on the West Coast: earthquakes. The city currently maintains that even if an earthquake causes the dikes to sink, they will be at an “acceptable” level.

It would be too expensive to make Richmond’s 49 kilometres of dikes earthquake-proof, so the city has focused on fortifying around the pump stations instead. One potentially big solution employs tiny microorganisms: the city is currently testing the ability of microbes to strengthen the soil under dikes.

Then there’s the question of what the future holds beyond 2100. With climate change, relying on dikes is a constant game of “catch-up,” having to build taller and taller dikes as sea levels rise and storms worsen, said Lyle.

Massive infrastructure projects for flood protection don’t come cheap, so it helps that spending isn’t controversial for vulnerable Richmond, said Ho. “Our residents and council, they get it,” he said.

It also helps that Richmond has a growing population. The federal government does have a disaster mitigation and adaption fund for municipalities, but Richmond has been building up its own piggy bank.

In the 2000s, the city implemented a special utility fee that Richmondites pay as part of their property taxes for flood protection infrastructure, essentially a flood tax. The city collects about $14 million a year, says Ho. his amount is only expected to grow, an impressive solution unparalleled in the region.

There are no plans to slow Richmond’s growth, as noted in its official community plan. Construction continues to boom along the water.

While standing on the city’s great wall of a dike, Ho reaffirms the commitment to building it up in time for that one extra metre of water.

“We’re not looking at retreating or relocating any of the existing infrastructure — we’re looking at protecting it all.”

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: