On Yekooche Reserve #3, an hour outside of Fort St. James, B.C., kindergarten to Grade 9 students at the Jean Marie Joseph band school get a lot of outdoor science education.

Whether they're rendering bear fat, setting trap lines, or cleaning game, kids spend four weeks out on the land every year, one week per season, learning how nature can provide for them.

But there isn't a lot for the kids connecting that experience to Western science education. In the small school of less than 20 students, science isn't taught in the primary grades, in favour of an intense focus on building literacy and numeracy skills. And with Grades 3 to 7 all in one class, the science taught has to strike a balance among different learning levels.

That's why the Yekooche First Nation -- especially the kids -- were excited to have entomologist and environmental consultant Lynn Westcott, visit their school twice as part of Science World's Scientists and Innovators in the Schools outreach program.

Westcott's first visit, in the fall of 2014, focused on insects and their place in the wider ecosystem: looking at bugs under the microscope and having students make their own insects out of art supplies.

Then in March she led a spring break science camp that involved more general science knowledge. It included more classic science experiments, like inflating a balloon using baking soda and vinegar, and making oobleck, a cornstarch and water mixture that has characteristics of a liquid and a solid.

Westcott's lessons made science fun, but also helped connect some of the kids' traditional knowledge, particularly about insects, to scientific knowledge.

"I think it just made them aware of the natural world in a different way," said Rachel Yordy, director of education and employment for Yekoochee First Nation. Particularly for primary students, "this is their first exposure to a lot of that."

Westcott has been volunteering with Science World's Scientists and Innovators in the Schools (SIS) program for eight years. But SIS has been providing this kind of exposure to real-live scientists to kids all over British Columbia for over 25 years.

Pulling from a pool of 200 volunteers from across the province -- scientists, new teachers, professors, and retirees from or students in those fields -- the program connects schools with real local experts to make science engaging while demystifying the role of a scientist.

"Taking away the misperception of 'scientists wear lab coats' and just putting real people in the classroom, that already bridges some of the gap and the misunderstanding," says Friderike Moon, program specialist at Science World, who manages SIS.

A STEM sell shortfall

B.C. students perform pretty well on science knowledge assessments. More than half who took the Science 10 exam in 2013/14 achieved a C+ or higher. Overall, only five per cent failed the course -- a passing rate that's remained steady, give or take a percentage or two, since 2006/07.

Internationally, our 15-year olds outperformed their peers in 66 other jurisdictions in the science section of the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (better known as PISA), a standardized test run by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Only two jurisdictions -- Hong Kong and Shanghai -- got higher marks, while seven others ranked similarly to B.C.

Yet there are still concerns that students aren't pursuing sciences beyond mandatory courses or after high-school graduation. Nationally in 2011, 18.6 per cent of Canadians with post-secondary credentials studied science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (also known as STEM) fields. To put that in perspective, 25 per cent had business management, marketing and related support services credentials, the most common field of study.

Half of those with STEM credentials are recent immigrants, and slightly less than a third were women -- although the latter number is slowly improving in some areas like biology, biomedicine, and physical sciences.

Governments and industry also worry that a lack of training in trades and technology has left B.C. with a skills shortage in those fields. The province expects one million job openings by 2022, the majority in skilled trades. In anticipation, it has directed post-secondary institutions to focus on training in areas of "high demand" skills.

The Council of Canadian Academies is unconvinced there's a crisis, saying there is no evidence of a STEM skills shortage in Canada. The Council says future industries, STEM or not, would be better served by establishing a significant base of science knowledge in pre-school to high school rather than wait until post-secondary to invest in the sciences.

"While there are many types of fundamental skills, STEM education provides a rich environment for developing … mathematics, computational facility, reasoning, and problem solving. These form the basis for more advanced STEM skills," the Council reported. "As a result, fundamental skills for STEM are important for all Canadians, regardless of occupation."

Stomp rockets

That's what SIS is trying to achieve: a basic understanding of science for as many young British Columbians as possible -- and the earlier the better, says Science World's Moon, even if visiting K-7 classes isn't always an SIS volunteer scientist's first choice.

"Teachers in elementary schools are generalists: they have to know so much, from social studies to languages to sciences, and it's really important that we support the teachers with the sciences," said Moon. "We don't want to lose the kids within the first seven years because they start to feel that science is not for them."

To counter that inclination, volunteers opt for hands-on, engaging science experiments that teachers or schools might not have the resources to run themselves.

For example, last year two SIS scientist volunteers visited Collette Shanner's Grade 3 class at Giant's Head Elementary in Summerland, B.C., to lead a lesson on basic physics. Specifically, on Newton's laws of motion.

Sounds yawn-worthy and complicated for a Grade 3 class. The scientists made it fun by having Shanner's class make "stomp rockets" -- so named because students gleefully "stomp" on an air-filled launcher to vault their toy rockets sky-high using nothing but air pressure.

Important lessons about physics are conveyed. But the kids are engaged not only in learning but also a lot of giggling, stomping, and bragging about how high or far their rockets fly -- more fun for your average nine-year-old than sitting quietly in their seat while a teacher reads a textbook explanation of how rockets work.

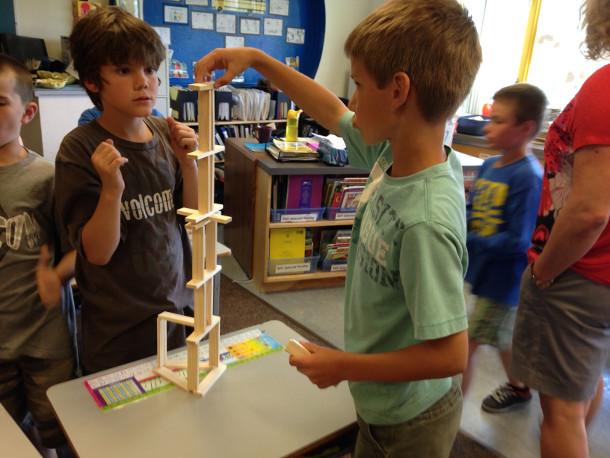

Shanner has used SIS for the past three years to bring in scientists and innovators, including an engineer who now returns annually to do a lesson in which students use blocks to build their own massive towers.

"Not only does it benefit my students, but it benefits me. It gives me more expertise as a teacher," she said, adding that she has since adopted stomp rockets into her own lesson plan.

Benefits for the children include a deeper understanding of how science concepts translate into the real world: like how buildings stand up, or rockets leave the earth. But the novelty of an outsider visiting the class with an interactive lesson isn't lost on them, either.

"They love it. Having any opportunity where they can do something outside of desk [work], where they're able to build and learn and experiment with things, is such a valuable experience for students," said Shanner.

Reduced reach

Volunteers do go to high schools, too. Brian Cameron, a science teacher at Charles Hays Secondary in Prince Rupert, B.C., has been using the program for four years to bring biologists and chemists into his Grade 9 to 12 classes.

In an email, Cameron said that because the scientists have expertise in their field beyond what teachers can provide, they give students already interested in the sciences "inspiration" and "a sense of wonder" about a field they might want to pursue after graduation.

"It feels like 'bring your parent to work day' because students are able to find out about the profession in an environment that is comfortable to them," Cameron wrote. "Students are shy at first, but they ask copious amounts of questions about the presenter's profession once they are comfortable."

Nonetheless it's harder to get high schools interested, Moon notes, partially from a perception that Science World itself is for younger kids. It may also be because the program's reach is a lot smaller than it used to be.

From 2005 until 2011, the B.C. government provided $1 million a year to the BC Program for the Awareness and Learning of Science that supported SIS, as well as Science World's travelling educational show, Science on the Road, and free fieldtrip admission to Science World. In 2012 that funding was cut.

The money not only helped reimburse SIS volunteers for travel and material costs, but trained them to scale down their highly complicated and technical work to a level that school children could not only understand but enjoy learning about.

"It was a huge setback for us," said Moon. It was so significant that Science on the Road was grounded for the last three years, and is only back in drive this year. Scientists and Innovators in the Schools saw visit requests plunge from 2,000 a year to just 500 to 700 after their promotion budget was slashed.

Today SIS receives $10,000 a year from AMGEN, a pharmaceutical company, and a grant from the federal government's Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council. Science World's operational budget tops up the rest -- it costs $90,000 a year to run just the Scientists and Innovators in the School program.

"I think [Science World is] doing pretty good at the moment," said Moon of the impact on their overall budget. "But of course we're not-for-profit, so there's a bit of an impact, and we're always looking for extra supporters and funders."

While Moon and her colleagues struggle to keep the program afloat, some of the schools that receive SIS visits have developed strong connections with the experts who come to their classrooms -- relationships that often continue even without SIS's help.

Entomologist Westcott is already in talks with the Yekooche First Nation to bring back the spring break science camp next year, this time working with elders to provide a direct link between their First Nations' teachings and western science education.

"I feel very comfortable with them," Westcott said about the kids. "I really appreciate being able to share my interests, but also sharing in their culture and learning from them, as well." ![]()

Read more: Education, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: