They were ten storeys above the forest floor. Four activists perched on two plywood platforms, suspended by thick ropes in a pair of massive Douglas firs.

Down below, anti-logging protestors wearing black t-shirts and camouflage eyed the RCMP team sent to dismantle their illegal blockade. The tree-sitters were barely visible from the ground, just a few fuzzy shapes where branches gave way to sky.

Nearby, a concrete bridge traversed a steep canyon. Rocky cliffs sank into the roaring white waters of Lava Creek dozens of metres below.

The activists had blockaded the bridge. They'd parked a brown pick-up truck sideways, and wrapped it in barbed wire. Long ropes attached to the tree-sitters' platforms descended from the green forest canopy, ran through conduit pipes wedged underneath the truck and went back into the trees. Two signs put up by the activists warned that tampering with the ropes would make the platforms fall -- and the tree-sitters would die.

It was July 28, 2000 when an RCMP aerial extraction team led by Inspector Bud Mercer arrived on this scene. Police had orders to clear the bridge so International Forest Products (Interfor) could continue logging the upper Elaho Valley. Mercer allegedly approached the blockade with a long-handled pruning rod, and cut the ropes attached to the platforms high above.

That incident would become the centre of a six-year legal battle and the climax of the Elaho Valley standoff. One of the tree-sitters claimed Mercer imperiled lives, while the Crown argued that activists lied to entrap police. In 2006, the B.C. Supreme Court cleared Mercer of any wrongdoing. Less than a year later, he was appointed to lead the Vancouver 2010 Integrated Security Unit, a $900 million behemoth charged with protecting the Olympic Games.

Loggers vs. activists

When Zoe Blunt arrived at the Elaho Valley in 1997, she saw herself as the defender of a pristine wilderness. She joined dozens of other activists determined to wage war against Interfor chainsaws. Most of the lower valley had already been logged. Activists feared an ancient grove of douglas firs -- some more than a thousand years old -- would fall next. Their camps were a three-hour drive north of Squamish, most of it on a bumpy gravel road. The road passed spectacular alpine vistas, patched with vast fields of stumps, before entering the un-logged forest. There, tree-tops loomed like skyscrapers. Huckleberry bush sprouted wild from the thick, peaty floor. Black bears, wolves, mountain goats and the odd grizzly roamed the woods. Blunt remembers Douglas firs so big a group of 12 people would have to hold hands to encircle them.

The activist camps were congenial places, where environmentalists shared instant noodles and peanut butter. They had climbing gear, video cameras and a satellite phone that cost five dollars a minute. In the summer it was hot. But the fall brought relentless rain. Blunt wore a green poncho, rain pants and a rugged wool coat -- and still she was drenched. The activists blocked roads and built platforms in the trees, but changed tactics often. Some days they'd simply hide in the forest, waiting for the loggers to come.

Blunt remembers listening for the first roar of a chainsaw. It was her cue to jump into the open, singing 'Oh Canada' or blowing a whistle. The loggers would drop their saws and chase her through the woods. She'd evade them, and circle back. Those cat-and-mouse games could last for hours. They made the loggers furious.

Two years passed this way. Interfor won court injunctions against the activists, but they kept returning to the woods. The loggers felt like their livelihoods were under attack by roving gangs of unemployed radicals. The end result was violence.

Camp under attack

On September 15, 1999, Western Canadian Wilderness Committee (WCWC) campaign director Joe Foy was in court. He was arguing against an injunction that kept his group from doing research in the Elaho Valley. During lunch break, his cell-phone began to buzz. Foy picked up. On the other end was James Jamieson, a WCWC conservationist working near an activist camp, calling from the satellite phone. Jamieson had shut himself up in his car. He could see dozens of loggers approaching. The call ended abruptly.

"From my point of view I've got a dead phone," Foy said. "Then we're back in court telling the judge something serious is happening but we're not sure what. What I knew was that we've got a mob of angry guys coming into the camp and Jamieson sounds scareder than hell."

Back at the Elaho Valley, 75 to 100 forest-industry workers had stepped down from logging trucks. There were eight people in the camp including Jamieson. He tried to stay calm as loggers walked up to his car. According to his account, the men forced a door open. One grabbed him by the thumb of his left hand while another pulled his fingers sideways. They dragged him out of the car and onto the ground. Someone lifted a 10-15 pound rock and threatened to drop it on his head, Jamieson claimed. Other activists were punched and kicked. Tents burned. Video cameras lay in pieces. Three Interfor workers and two contractors later pled guilty for taking part in an attack that sent Jamieson and two others to hospital.

Platforms high in the trees

The confrontation left activists shaken, but hardened their resolve. More remote camps had not been touched and others were built soon after. The real climax of the Elaho Valley standoff came next summer.

In late July 2000, activists built an elaborate blockade at Lava Creek. A few experienced tree-sitters from the United States helped them put it together. First, activists parked an old Ford pick-up -- named 'Big Brown' -- sideways across the bridge. Then they filled the truck bed with rocks and heavy logs. They leaned more logs against the truck and wrapped the entire thing in barbed wire.

Tree climbers lugged thick plywood platforms high up into the foliage of two tall firs. Looking down, the bridge blockade would have appeared tiny, and much further below it, the raging creek. The tree climbers scaled the massive trunks with two webbing straps. Harnesses clipped onto the top strap. Leaning on the harness, the climbers could pull the bottom strap up. Then they'd stand on the lower belt to take weight off the top, and move the upper strap higher. The climbers ascended 50 metres this way.

It was arduous work. They tied ropes to branches in the green forest canopy to secure their platforms. They could move from one sheet of plywood to the other by shimmying along a perilous traverse line. Long ropes descended to the blockade far below. Here, the ropes ran through conduit pipes underneath the brown truck.

Activists claimed the safety of their platforms depended on these supports. Rebecca Avrett, Jonah Fertig, Dennis Zarelli and Trevor Schatz began their vertigo-inducing vigil on July 25, 2000. The next day, RCMP officers came to take them down.

'So I did cut the ropes': Mercer

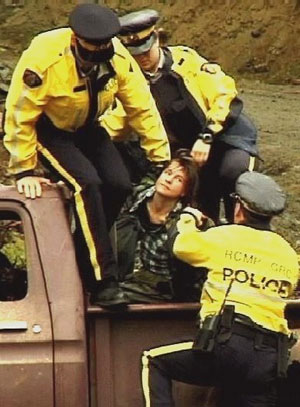

Zoe Blunt was the first to be arrested. The activist got into a heated argument with officers sealing off the bridge site with bright police tape. A female officer hip-checked her, she claimed, and Blunt took off into the forest. Police in yellow RCMP jackets and black boots soon caught up and put her in handcuffs. They drove her out of the Elaho Valley that day.

Meanwhile, eight officers kept watch over the bridge. On July 28, after two days in standstill, they called in the RCMP's aerial extraction team, a specially-trained unit led by inspector Bud Mercer.

In the summer of 1993, Mercer's skill as a recreational climber had attracted the attention of his superiors. He and a colleague were teaching at a Squamish climbing school. He was called to a massive anti-logging protest at Vancouver Island's Clayoquot sound. A senior officer asked Mercer if he could get activists down from the trees. "I packed up my stuff and my gear," he said. "It was a pretty simple problem to bring these individuals out of their perches. It wasn't that complex at all to do it and do it safely."

Over the next seven years, Mercer trained and worked with six officers skilled in high-altitude rescue. During a decade of fervent anti-logging protests, the team was deployed often. So when Mercer arrived via helicopter at the Elaho Valley, it was just one more assignment.

On July 28, about 30 RCMP officers removed the barbed wire and logs from the activists' bridge blockade. There was still the question of the tree-sitters. Mercer tested the long ropes ascending from the truck into the fir trees above. "It did not take very long to learn conclusively that the ropes were props and they had absolutely nothing to do with their anchor system," he said. "So I did cut the ropes."

Lives in danger or police entrapment?

What happened next depends on who you ask. Blunt claims the tree-sitters' platforms shifted suddenly, and dropped a few inches. Screams rained down from the foliage. "The people in the trees were terrified by all accounts," Blunt said.

Mercer remembers differently. The tree-sitters didn't actually see him cut the ropes, so their reaction was delayed. He claims the whole thing was a set-up. What is certain though, is that police waited five long days for the tree-sitters to surrender. High up in their perches, the activists had plenty of dried food. But the sweltering 35 degree Celsius heat sapped all the moisture from their mouths. They climbed down on August 2, thirsty and weak. They were promptly arrested, but released after they agreed to stay away from the Elaho Valley.

Not long after the incident, tree-sitter Dennis Zarelli successfully laid four charges of aggravated assault against Mercer. A justice of the peace in Squamish agreed the inspector had endangered lives. The judge ordered Mercer to appear in court on Nov. 28.

Somehow the decision was leaked to the media before charges could be officially registered. So Mercer was caught off-guard when his parents, wife and children saw his name in glaring newspaper headlines. But the charges never stuck. A month later, the case against Mercer was tossed after the crown reviewed a police videotape of the rope-cutting incident. Zarelli himself was put on trial -- for allegedly lying to the courts.

Mercer's name cleared

On December 12, 2006, Zarelli was convicted of obstruction of justice by B.C. Supreme Court judge Sunni Stromberg-Stein. Crown attorney Ralph Keefer successfully argued the former tree-sitter had a personal vendetta against Mercer, that the platform ropes were a ruse, and none of the activists were in real danger.

"I feel pretty good, I've got to tell you. It's been six years since he laid this charge against me," a relieved Mercer told the Vancouver Sun after the verdict was declared.

The court's decision still rankles Blunt, who thinks Mercer could have killed her friend. "The platforms were not designed to trap police," she said. "It was designed to put people in harm's way and delay the logging for as long as possible."

To a certain degree, the Lava Creek blockade -- and the years of protest that preceded it -- was a success. In May 2001, the Squamish First Nation released a draft plan to designate the upper Elaho valley a Wild Spirit Place. That same month, the provincial government declared a moratorium on logging. And in June 2007, it passed legislation ensuring the valley's protection.

Mercer still retains a clear memory of the day he cut the ropes at the activist blockade. Though he stressed it was only one assignment among many. He'd like to go climbing someday, but protecting the 2010 Winter Games keeps him too busy. "It's a sport that you have to put aside a day to do," Mercer said. "And I haven't had the luxury of that kind of time." ![]()

Read more: 2010 Olympics, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: