The B.C. First Nations Health Authority opened its gathering to present a grim report on toxic drug toxic deaths in 2022 with a song, a prayer of hope and unity for the families and friends affected by toxic drugs.

The report found toxic drugs have been taken a disproportionate toll on First Nations members, who were almost five times as likely to die of drug poisoning in 2022 than non-Indigenous B.C. residents. Although representing only 3.3 per cent of the province's population, Indigenous people represented 16.4 per cent of toxic drug poisoning deaths in 2021.

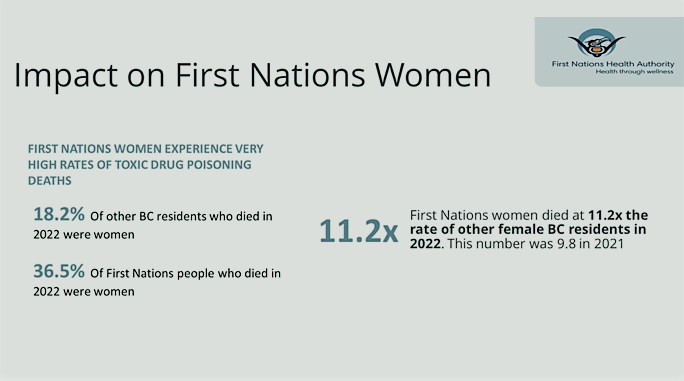

The numbers are also dire for women. In 2022, 36.5 per cent of the First Nations people who died were women, twice the rate for non-Indigenous people.

“When I think about toxic drug deaths, I think about pain. I think about self-medication. I think about the causes of that pain. I think about systemic failure to look after those in pain,” said Stó:lō Grand Chief Doug Kelly.

Dr. Kelsey Louie of the Tla'amin Nation, the authority’s acting deputy chief medical officer, said First Nation individuals and communities have been “particularly, disproportionately impacted by the toxic drug supply — with a loss of life that is unacceptable.”

Louie said the authority’s approach begins with listening to communities and families who had lost loved ones to learn how to expand “our role in preventing toxic drug poisonings. And stop the harm being done today.”

Kelly said the crisis requires a broad response.

“Our children are vulnerable. Parents, families, communities, teachers, schools, coaches, everyone that comes into contact with children have an opportunity to support them, grow them, develop them, heal them,” he said.

Health authority CEO Richard Jock, a member of Mohawks of Akwesasne, said the COVID-19 response has dominated public health, and the authority knew mental health would be the next challenge.

“We certainly didn't anticipate the level of effects from toxic drugs that we're seeing today.”

The level and nature of drugs are changing, he said, and partnerships with First Nations communities and provincial and federal governments also need to change.

Jock said the toxic drug emergency is now the First Nations Health Authority’s top priority and it was “gearing up our response for deploying and redeploying resources, both human and financial, to meet these emerging and changing needs.”

Part of the work is tackling barriers and obstacles in the health system, said Jock, recognizing intergenerational trauma. “We need to acknowledge that the trauma is a key element and underlies much of the issues that we're facing today, including toxic drugs.”

Acting chief medical officer Dr. Nel Wieman, of Little Grand Rapids First Nation, said action is needed on a public health emergency entering its eighth year. “It starts to feel more like the status quo, and we cannot accept this. We have to treat this for what it is — a public health emergency.”

“First Nations communities across B.C. have lost too many loved ones to an increasingly toxic drug supply. And that loss of life is now more than 1,000 family members and friends,” Wieman said. “It gives me great sadness to report that in 2022, there were 373 deaths among First Nations people.” That is a 6.3-per-cent increase over 2021.

Wieman said the disproportionate impact on Indigenous people is linked to the history of trauma in people's lives, along with intergenerational trauma.

And First Nations people report less access to mental health, wellness and substance use treatment that is culturally safe and appropriate, she said. “Systemic racism toward First Nations is a barrier to health care.”

First Nations are also are more likely to face poverty and housing challenges, which are among the social determinants of health. “These are also predictors of substance use disorders,” Wieman said.

Wieman said the health authority recognized the disproportionate on First Nations women. It has “pivoted our toxic drug crisis response to have a greater focus on First Nations women, and has dedicated a portion of our harm reduction outreach and engagement programs to support women, especially in urban areas.”

The speakers agreed on the need to build hope and address the causes of toxic drug deaths.

Wieman said there’s a need to “change our understanding of the root causes of substance use and addiction, and work together to address the stigmas surrounding drug use and the people who use drugs.”

Katie Hughes, the health authority’s vice president for public health response, says “Our strategy is to build on First Nations people's strengths and resilience, address root causes, and provide holistic healing and wellness supports to First Nations people regardless of where they live.”

Hughes also outlined new initiatives. The authority will meet people where they are in their wellness journeys, she said. Treatment centres will move to a healing and wellness approach, and will expand to regions that are underserved. The authority is investing in land-based healing initiatives and expanding healing pathways for those who have lost a loved one to this crisis.

It’s also focused on “efforts and investment in additional areas, including securing new funds to enhance wraparound services directly in communities,” said Hughes. That includes First Nations-led overdose prevention and mobile harm reduction services and working with the province to provide detox and treatment beds specifically for First Nations people.

“We've recently utilized one-time funding to partner with eight treatment centres across the province that provide withdrawal management and treatment services to support individuals at higher risk who require immediate access,” she said.

The health authority also wants to expand peer support networks.

Grand Chief Kelly has a deep connection to the crisis. He lost his daughter during her healing journey of recovery and shared what he had learned.

“Conditional love doesn't work,” he said. “Do not shame your child or your loved one. Do not judge. Simply be there. Simply be there. Walk with them,” he said.

Culture, language, spirituality can all guide loved ones to wellness, he said, but if supports and resources are offered conditionally, for example only if people attend abstinence models of treatment, they are not meeting needs.

Kelly spoke of Indigenous housing organizations that kick out young women when they're struggling. “We have to create shelter that's going to have that approach of unconditional love,” he said. “Kicking 'em out puts them on the street, and that's a direct path to self-destruction and death. So I'm hopeful that each and every one of you will raise the profile of these public issues, — housing, safe shelter.”

“We have to work together to improve services from all of the agencies that come into contact with children,” said Kelly, “To make sure that the health-care system is providing quality care each and every time they engage someone in pain, that they look after them in a good way.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: