[Editor’s note: On Oct. 8, 1952, the Kenney Dam blocked the flow of water into the Nechako River, forming a massive reservoir and hydroelectric facility to create an aluminum industry. Seventy years later, The Tyee explores the lasting impacts of the Nechako Reservoir and work underway to restore some of its damage. Second in a three-part series.]

The downstream effects of the Kenney Dam weren’t felt right away.

Growing up on the Saik’uz First Nation in the 1970s, Chief Priscilla Mueller remembers a time when the Nechako River was overflowing with spawning salmon in July and August. Elders would set nets and families would help clean the fish. Smoke shacks ran continuously, preparing the food for winter, and freezers would be filled with the abundant stocks.

“When I was a little girl, I remember cleaning 200 fish in one day,” Mueller says. “All our summer, all our August, was just fish every day. Preparing fish, drying fish, canning. We’d spent weeks doing that.”

Sometimes they would catch a Nechako white sturgeon — a feast that would feed several families.

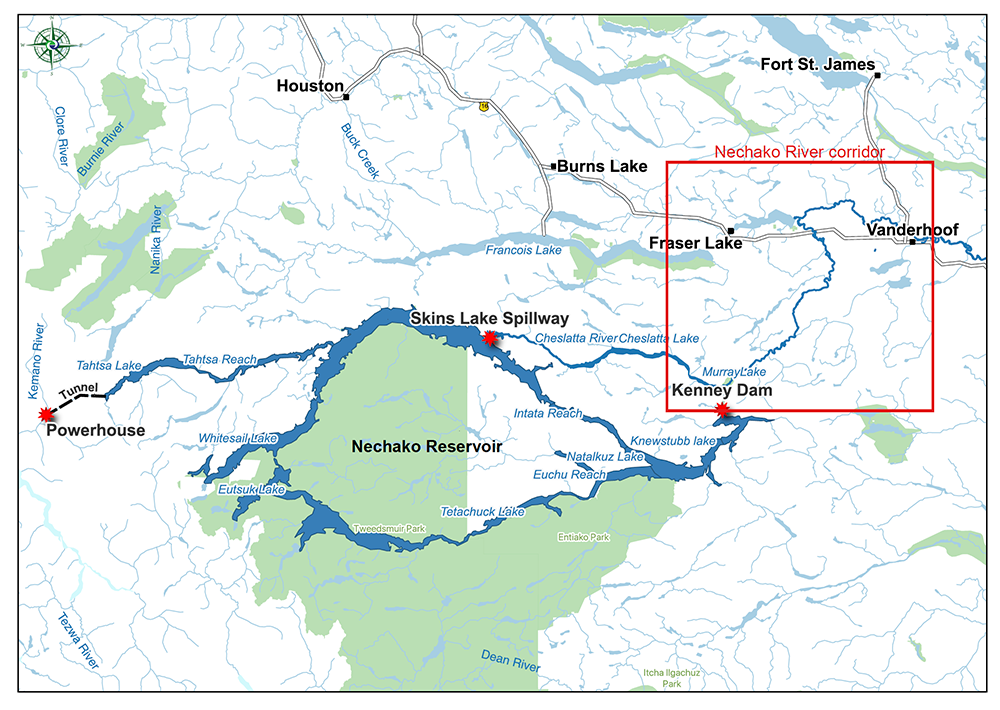

That was decades after Rio Tinto Alcan, then the Aluminum Co. of Canada, dammed the Nechako River, creating the Nechako Reservoir to power its aluminum smelter on the coast near Kitimat. The dam effectively reversed the river’s flow, sending two-thirds of its volume back toward the Coast Mountains and the hydroelectric power turbines buried within them.

In the years that followed, water temperatures in the Nechako River began to warm. Gravel riverbeds favoured by spawning salmon and white sturgeon gradually filled with sand and silt, carried downstream by the river’s flows when water was released from the reservoir.

By the time Mueller was a teen in the 1980s, the supply of fish from the river had almost ended.

“Now if we get salmon here, we have to bring it in,” she says. The community’s salmon is bought from Prince Rupert, 600 kilometres away.

Nechako white sturgeon were also harmed. Of about 500 adults remaining in the river today, most were born prior to 1967 — the year when researchers mark a sharp downturn in the fish’s natural ability to reproduce. The genetically distinct population is now listed as “endangered" under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

The solution, Mueller and neighbouring downstream communities say, is a return to more natural flows to the Nechako River. It’s a request they’ve taken as far as the B.C. Supreme Court in their bid for greater control over how the river is managed.

“The dam is destroying the river,” Mueller says. “I think it’s all about money. It’s not about the environment. Otherwise they would come to the table and say, ‘Yeah, let’s look at these solutions. Let’s work together.’”

That time a company reversed a river

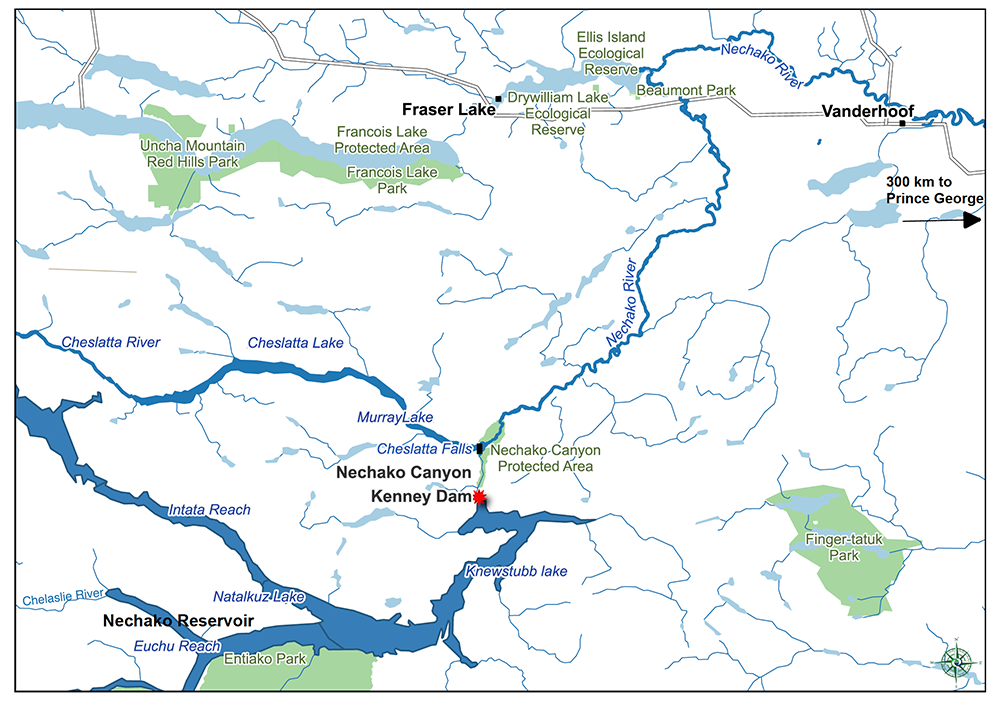

The Kenney Dam is a 100-metre-high clay and rock embankment about 100 kilometres southwest of Vanderhoof, B.C.

Nearly half a kilometre across, it spans the Nechako Canyon. A road across the dam offers views into the canyon below. Once a commanding waterway, its riverbed is now dry and trees fill the gully.

While the dam took years to build, flows into the upper Nechako River officially ceased on Oct. 8, 1952.

Water backed up into a chain of lakes that extend more than 200 kilometres to the west. It flooded homesteads, Indigenous village sites and forests, the standing timber left to rot and tumble into the reservoir. At 900 square kilometres, the Nechako Reservoir is B.C.’s second largest waterbody after the Williston Reservoir.

Most of the water in the reservoir is released to the west, through a 16-kilometre tunnel that feeds the Kemano hydroelectric project. But a smaller amount — about a third of the river’s original volume — takes a circuitous route to enter the Nechako River through a spillway 80 kilometres west of the dam.

Fearing impacts on salmon, Fisheries and Oceans Canada ordered Alcan to release water seasonally through Skins Lake Spillway when the dam was built. The releases were meant to lower water temperatures in the upper Nechako and provide sufficient flows during spawning season.

Water from the spillway carved a new, kilometre-long trench into Skins Lake. From there, it enters the Cheslatta River, travelling through Cheslatta and Murray lakes before pouring into the Nechako River eight kilometres below the dam.

It carries with it the sandy, crumbling banks of a river whose unnatural fluctuations have caused it to erode over decades.

A changing environment

Gerry Thiessen was born a year after the Kenney Dam was built. He grew up in the heart of Vanderhoof, in central B.C., blocks from where the Nechako meanders past the community’s downtown. Some of his earliest memories include playing on the gravel bars that braided the river.

Today, those gravel bars no longer exist.

Silt and sediment have filled in the gravel, allowing willow and alder to grow up. Since the dam was built, there is no longer a powerful spring runoff to scour the riverbed, wash away the silt and prevent the scrubby brush from taking over the islands.

“Certainly, I’ve seen changes,” says Thiessen, who raised a family and built a successful real estate business here. After 14 years as mayor, he chose not to run in the recent election. “I remember, as a kid growing up, going down and just seeing lots and lots of gravel down there. Now you see a lot of silt, and stuff like that, in the river.”

But it wasn’t just the dam that changed the river. Agriculture and logging, which Thiessen describes as the “mainstays” of the local economy, have also denuded the landscape. Climate change has brought impacts like mountain pine beetle and more wildfires, resulting in increased erosion.

The river is no longer the one he knew growing up, Thiessen says.

“Our river has changed a lot from when I was a kid. It used to be that you would go down the river and fishing for trout was no big deal. There was lots there,” he remembers. “It’s different now. We need to work together to find a solution here. But it’s going to take everybody being involved.”

Sediment accumulates, temperatures warm

For Steve McAdam, there’s no doubt that the Kenney Dam played a pivotal role in the perilous decline of Nechako white sturgeon. A biologist with B.C.’s Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship, he has studied the fish for more than 20 years.

He says that, unlike their neighbours in the Fraser River, the Nechako population is experiencing “recruitment failure,” or the inability to reproduce naturally in the wild — an issue made more alarming this summer by the dozen white sturgeon that mysteriously turned up dead along Nechako riverbanks.

They aren’t the only white sturgeon population in B.C. to suffer such a fate. To the east, populations in the Columbia and Kootenay rivers are also listed as “endangered” and struggle to spawn naturally.

The rivers all bear one common trait.

“They all have dams,” McAdam says. “If the dam wasn’t there, we wouldn’t expect to have recruitment failure.”

While the dam delivered an initial blow to the watershed — one that could have been more easily managed in isolation — impacts that came after, like logging, agriculture and climate change, added to the complexity.

A team of researchers at the University of Northern British Columbia has been studying the various compounding impacts.

“The reservoir has undoubtably caused lots of changes, but then there’s all these other cumulative ones as well,” says Philip Owens, a professor in landscape ecology at UNBC whose research traces the source of sediment in the Nechako River.

While the dam and reservoir have contributed to sediment and sand choking the gravel riverbed, he says the loss of vegetation through agriculture, wildfires and logging — which not only contribute sediment, but harmful pollutants like heavy metals and hydrocarbons — are also to blame.

“If it hadn’t been for all these other changes, it might be a lot easier to just identify the effect of the reservoir and its operation, but now you’ve got everything else laying on top of that,” he says.

Climate change is another one of those layers, says UNBC environmental science professor Stephen Déry. Air temperature in the watershed has risen about two degrees since 1950, resulting in an average water temperature increase of about 0.7 degrees, he says. That can have a negative impact on fish in the river.

“Those are significant water temperature increases,” Déry adds.

Conversely, he says simulations have shown that the summer temperature management program, when water is released through the Skins Lake Spillway to keep river temperatures below 20 degrees while salmon are in the river, has successfully countered the effects of climate change in the main stem of the upper Nechako — though only during the period that the releases are in effect.

When it comes to identifying reasons for fish declines in the Nechako, there’s no smoking gun, adds UNBC fisheries expert Eduardo Martins.

“It’s quite complex,” he says. “I think saying that the dam has no impact would be a bit naive… but also you have all the other impacts that could be happening in the watershed.”

From a legal perspective, that makes it difficult to pin responsibility on a single entity.

The legal case for protecting fish

In court, Rio Tinto Alcan has denied responsibility for decimating fish populations in the Nechako.

Saik’uz and Stellat’en First Nations have fought the company over its impacts on the river for more than a decade. Their B.C. Supreme Court case, launched in 2011, attempts to force Rio Tinto Alcan to “reinstate the functional flows that make up the natural flow regime of the Nechako River.”

In their claim, the First Nations say the dam had a profound effect on the fishery, resulting in the “imminent extirpation of the Nechako white sturgeon and a substantial reduction in the population of salmon.”

That has violated their Indigenous right to fish, they say.

But Rio Tinto Alcan “contests virtually every aspect of the plaintiffs’ claims,” according to a January decision by Justice Nigel Kent. The company denies that its management of river flows diminished fish stocks “in any material way,” calling the claim “simply not proven.”

In his decision, Kent affirmed the First Nations’ right to fish for food, social and ceremonial purposes and acknowledged that right had been “significantly impaired” by regulation of the Nechako River.

But he ruled that Rio Tinto Alcan could not be held responsible for its role in depleting fish stocks as it “strictly complied with all regulatory requirements” imposed by government.

“The damage to the fishery is the inevitable result of those authorizations, and RTA cannot be held liable to the plaintiffs on that account,” Kent wrote.

The ruling also summarized all the times Rio Tinto Alcan pushed back against government’s attempts to preserve fish stocks in the Nechako.

The company began selling surplus power to the BC Hydro grid starting in the 1960s and ramped up production through the 1970s, it says. By 1979, it was not meeting its commitment to discharge sufficient water through the spillway, despite repeated requests by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs to do so “for the safety of migrating and resident salmon.”

Instead, the company deferred to B.C.’s Comptroller of Water Rights, which it regarded as the authority over water releases. The corporation told the fisheries minister it would not comply with the requests from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, Kent’s decision states.

The fisheries department took its concerns to the B.C. Supreme Court, which ordered Alcan to comply with flow releases set by the federal government in August 1980. It granted an injunction requiring the company to release the water that was continually renewed until 1985, when the company opted to take the issue to court.

In the end, the province and Rio Tinto would enter into a settlement agreement in 1987 that would determine the flow levels into the Nechako River that continue today. But the agreement would exclude any input from local First Nations.

At issue was whether the company should be required to release the “preferred” flows that could rebuild fish stocks or “base” flows sufficient to maintain current populations. Against advice from its own scientists, the federal government opted to pursue the base flows that would provide less than half the water volume needed to restore salmon and sturgeon. The fisheries minister expressed concern about the “relative economic benefits of enhancing salmon runs to the detriment of RTA’s economic contribution,” according to Kent’s January decision.

The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council and a dozen First Nations, including Stellat’en, Saik’uz and Cheslatta, went to court in 1986 and won the right to join the case against Rio Tinto Alcan. But that decision was successfully appealed by the company and the province.

As a result, the following year First Nations impacted by the dam were cut out of the settlement agreement that established current flow regimes for the Nechako River.

Chief Mueller believes that if the First Nations had been given a say in how river flows were managed decades ago, fish stocks in the Nechako might not be in their current state.

“When they established that flow regime in the 1987 agreement, it was Canada, B.C. and Alcan. There was no First Nations community at that table…. When they built the dam, there was no First Nations people at that table. We look at the state of the river now, and it’s almost destroyed,” she says.

Rio Tinto Alcan says it can’t comment on the ongoing court case, which is now being appealed by Saik’uz and Stellat’en.

But Andrew Czornohalan, operations director at Rio Tinto BC Works, says there has been more community involvement in Nechako River flows in recent years than at any other time in the dam’s history.

He points to the Water Engagement Initiative, which gathers community feedback on flow management, and says the company is working with First Nations and local communities “to improve the water flow into the Nechako River while still monitoring for flood risks in Vanderhoof.”

“If we can facilitate a conversation amongst all of those interest holders, and we can actually understand the technical detail of an interest, potentially we can define and navigate a path forward which is better than the status quo,” he says.

Rio Tinto Alcan says it is trying to make incremental changes to improve watershed health. This year, it released water through the spillway at a more gradual rate, resulting in a more natural flow that is more like a river that hasn’t been dammed, Czornohalan says.

The company also points to its $50-million commitment to the Nechako Environmental Enhancement Fund, money earmarked for watershed improvements. Work that’s benefited from the fund includes the Nechako White Sturgeon Recovery Initiative and watershed research underway at UNBC.

The company is also exploring the feasibility of a cold-water release facility at the Kenney Dam. Something long called for by local communities, it could deliver cooling water to the Nechako Canyon, incorporate a hydroelectric facility providing economic development for First Nations and reduce impacts on the landscape.

A preliminary study currently underway will look at design options and cost for the facility, Czornohalan says.

But the facility could cost hundreds of millions of dollars, he adds. While about $40 million remains in the Nechako Environmental Enhancement Fund, it’s unclear who would fund the rest.

The B.C. government declined a request to be interviewed about a water-release facility at the Kenney Dam. It also did not respond to questions about whether it would consider paying for the facility or how it is seeking resolutions in the Nechako watershed, given the recent B.C. Supreme Court decision and the responsibility it placed on the provincial government.

In an email, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests says the province is aware of “interest from First Nations and stakeholders” in a water-release facility and that assessments have been undertaken on potential benefits, design options and cost.

But a release facility at the Kenney Dam would be “the responsibility of the water licensee, Rio Tinto,” the ministry says.

Both B.C. and Rio Tinto Alcan profit from water diverted from the Nechako River.

According to BC Hydro’s financial statements, the provincial Crown corporation paid the mining giant nearly $100 million annually, on average, over the past decade for surplus power sold to the northern B.C. grid.

In return, Rio Tinto Alcan paid roughly $18 million annually to the province between 2008 and 2017 for water use, according to documents filed during the Saik’uz and Stellat’en court case.

Working together for the watershed

The idea that private industry should profit from a river to the detriment of local communities doesn’t sit well with Thiessen.

“The original intent was to provide jobs and the economy,” says the former mayor who, until the municipal election, also sat as chair on the Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako board. “It’s a resource that’s far too valuable. The world has changed. We didn’t realize that climate change was going to come. We didn’t realize what the impact was going to be.”

Last year, the regional district and Nechako First Nations — Saik’uz, Stellat’en and Nadleh Whut’en — agreed to work together on a path forward that balances economic benefits with environmental stewardship.

“It’s my hope that the fact that we’re working together now is making government and industry look at us and say, ‘OK, we need to understand the impacts of this,’” Thiessen says.

The regional district first declared its intentions in a February 2021 resolution that recognized the Nechako River was “no longer a functioning ecosystem.”

The resolution placed blame directly on the Kenney Dam and Nechako Reservoir for creating unnatural flows that caused “lasting, major damage to the populations of salmon [and] sturgeon” and acknowledged “significant infringements on the claim of Aboriginal title and rights of First Nations.”

It urged Canada, B.C. and Rio Tinto to “do all things necessary to support the efforts of the Nechako First Nations to restore the ecosystem functioning of the Nechako River.”

One year ago, the regional district and Nechako First Nations formalized their commitment to work together with a memorandum of understanding. It calls for the 1987 settlement agreement to be replaced with a new co-management framework that will include community input and return more natural flows to the Nechako.

No simple solutions

Researchers say there is no sure-fire solution to the myriad issues that plague the watershed.

It would be tricky to build a water-release facility in the Kenney Dam that ticks all the boxes, the UNBC team warns. Water cool enough to lower river temperatures would need to come from the bottom of the reservoir, where it would also be low in oxygen. A hydroelectric project would skim water from the top, where the water is warmer.

Also, notes McAdam with B.C.’s Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship, higher flows haven’t necessarily cleaned up habitat or led to higher salmon and sturgeon populations in the past.

“I'm skeptical that it will be the solution,” he says. “The challenge is, when people say, ‘restore flows to benefit sturgeon,’ when you think of the flows that might be required, you’re starting to flood communities. There’s a real trade-off.”

McAdam has been working on ways to restore spawning habitat by adding gravel to the riverbed near Vanderhoof. While the project showed some success, with two dozen white sturgeon born in the Nechako that year, one of the beds quickly filled with sand, he says.

He’s now investigating ways to remove sand from the riverbed or prevent it from settling in spawning beds in the first place.

“We did get some fish out of it, so that's definitely a positive result,” he says. “It makes me hopeful.”

UNBC’s Owens agrees there’s reason for optimism. He says reducing the amount of sediment entering the river would, over time, reduce or eliminate the damage to the spawning beds. “We can stop, in some cases, some of that sediment coming off the landscape,” he says. “It’s certainly not a hopeless situation at all.”

While researchers grapple with the question of how to repair habitat, a facility in Vanderhoof is working to keep endangered Nechako white sturgeon alive.

Under the hum of fans and dimmed florescent lights, juvenile white sturgeon circle in their cylindrical containers at the Nechako White Sturgeon Conservation Centre’s sturgeon hatchery. It’s the only home they’ve ever known, located in downtown Vanderhoof a stone’s throw from the river, where they’ll be released once they reach two years of age.

“The idea behind this facility is to be a stopgap solution,” hatchery manager Mike Manky says. “They seem to survive better after release, so it seems to be working.”

For a time, Chief Mueller moved away from her home community at Saik’uz First Nation. When she returned, more than just the river had changed.

The summer fishing, cleaning and smoking no longer took place. It meant a loss, not just in terms of food sources, but to the social fabric and culture of the community that had gathered every summer for longer than anyone could remember.

Today, she just wants to be part of a solution that helps to restore flows and, hopefully, repair the damaged fishery.

“If they had the First Nations communities involved, it would have been different. That river would have been different. I don’t think we would have lost what we’ve lost today,” she says.

In July, Saik’uz and Stellat’en filed an appeal to the B.C. Supreme Court decision that acknowledged their losses but didn’t hold Rio Tinto Alcan accountable, saying “the trial judge left the appellants with no relief.” They expect a decision on whether it will proceed early in the new year.

The nations say they want a new agreement to replace the one they were shut out of in 1987 — one that benefits all downstream communities and resolves the issues currently before the court.

In early October, they renewed their calls for Rio Tinto Alcan to restore more natural flows to the river, in light of the recent surge in white sturgeon mortality.

“For us, it’s not about the money. It’s about the river and restoring the river. It took 50 years to almost destroy the river. It’s going to take another 50 years, at least, to fix the flow and make it into a healthier river,” Mueller says.

“We’re not asking for much. We’re just asking that we be part of decision-making.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: