[Editor’s note: On Oct. 8, 1952, the Kenney Dam blocked the flow of water into the Nechako River, forming a massive reservoir to feed a hydroelectric facility on the coast. Seventy years later, The Tyee explores the lasting impacts of the Nechako Reservoir and work underway to restore some of its damage. Third in a three-part series. ]

James Rakochy holds his coffee mug with one hand and gestures with the other as he speaks. As if driven by a sixth sense, it migrates to the jetboat’s steering wheel each time he needs to swerve around floating debris.

“You’re in good hands with me,” he shouts over the roar of the engine, expertly navigating standing dead trees with the precision of a slalom skier. “I’ve been on this reservoir for a long time.”

Rakochy has been the Cheslatta Carrier Nation’s land and resources manager for more than 20 years. The Nechako Reservoir has been here less than a half century longer.

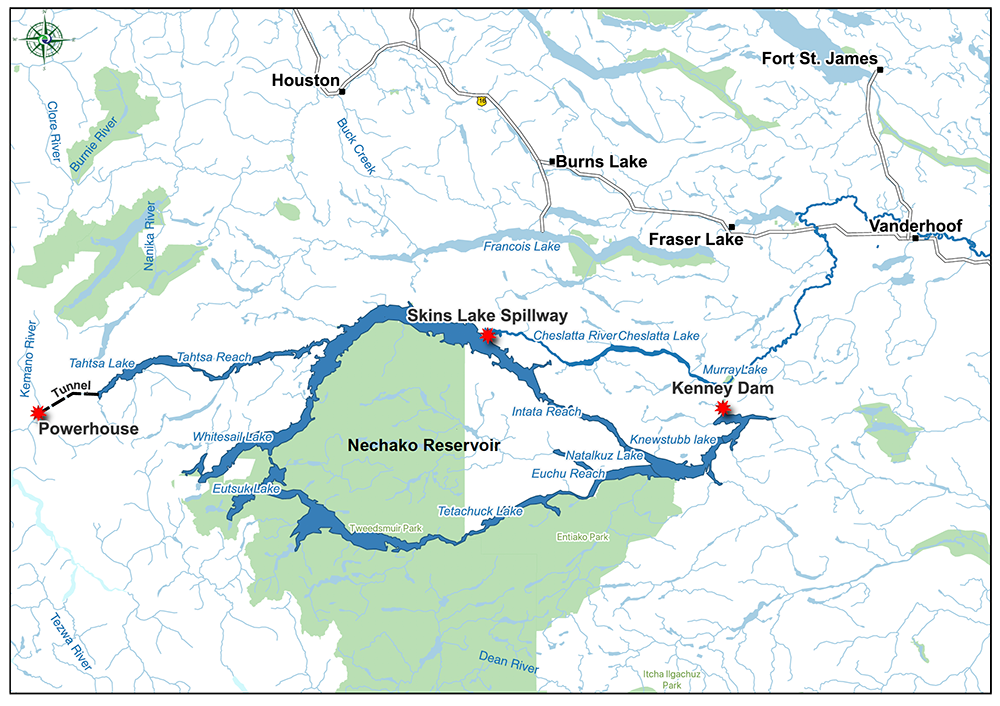

The 900-square-kilometre waterbody began to form on Oct. 8, 1952, when the Kenney Dam first blocked flows into the upper Nechako River. As the water backed up, it reversed most of the river’s flow, sending two-thirds of its volume west toward Rio Tinto Alcan’s Kemano Powerhouse, embedded in the Coast Mountains, to power the company’s aluminum smelter in Kitimat.

A chain of lakes more than 200 kilometres long in an arc around the northern boundary of Tweedsmuir Provincial Park flooded its banks, creating a massive waterbody twice the size of Okanagan Lake and 10 times the size of the reservoir planned for Site C dam.

From where we just launched at Skins Lake Spillway, the reservoir is about five kilometres across — roughly double its original width.

The dead trees left behind form a palisade along its shoreline. Over decades some have rotted and tumbled into the reservoir, creating rafts of floating logs and washing up on beaches. In midsummer, with water levels at their peak, driftwood floats off the beaches around the reservoir.

The debris has not only made boating hazardous, it’s created a barrier for wildlife. As we motor through the standing dead trees, a black bear swims across our path, crossing what decades ago would have been dry land.

Caribou have also been significantly impacted by the reservoir. Relatively high female caribou deaths and low reproduction rates have hit the caribou since water first surrounded the higher-elevation areas where they prefer to give birth.

But don’t call them islands, Rakochy cautions.

“We call those hilltops,” he says. “It’s all that’s left of Cheslatta land that was flooded.”

In the shallow bays, where dead forests stand like ghosts, Rakochy kills the engine. We float silently amongst the trees, the jetboat rolling lazily over a floating log. It’s as peaceful as a cemetery.

But the trees teem with life.

Their branches cradle osprey nests, at one time — according to an obscure B.C. government survey from the 1990s — the largest population in the province, and as we drift the birds soar overhead and tend to their young. They’re joined by cormorants, the primarily coastal birds appearing happy to bed down with large raptors as neighbours. Rakochy estimates he’s counted nearly a dozen of their nests in the area.

“This is my favourite place in the world,” he says. “Sometimes when I’m having a bad day, I just come out here.”

A barrier to migration

Not everything has fared so well on the reservoir.

When the Kenney Dam blocked flows into the Nechako River, it had catastrophic impacts on salmon and white sturgeon downstream. To make up for the lost flows, the federal government required the Aluminum Co. of Canada — which would later become Alcan and, after a 2007 merger with the multinational mining giant, Rio Tinto Alcan — to release water through a spillway at Skins Lake into the Cheslatta River system. The water enters the Nechako River eight kilometres downstream of the dam.

Releases through the spillway can approach 100 times the river’s original volume, tearing through the channel during salmon migration. Initial flooding displaced Cheslatta villages and decades of erratic flows have eroded shorelines, disturbing the nation’s ancient villages and gravesites and carrying silt downstream where it clogs spawning beds.

Cheslatta Lake is, in fact, a cemetery — it was consecrated in 1993 by a visiting priest in recognition of the graves submerged by the flooding.

Life on the reservoir itself has also been affected.

“Anytime you flood nine lakes, there’s going to be an impact on any wildlife species, be it terrestrial or aquatic,” says Cheslatta’s implementation co-ordinator Jim D’Andrea.

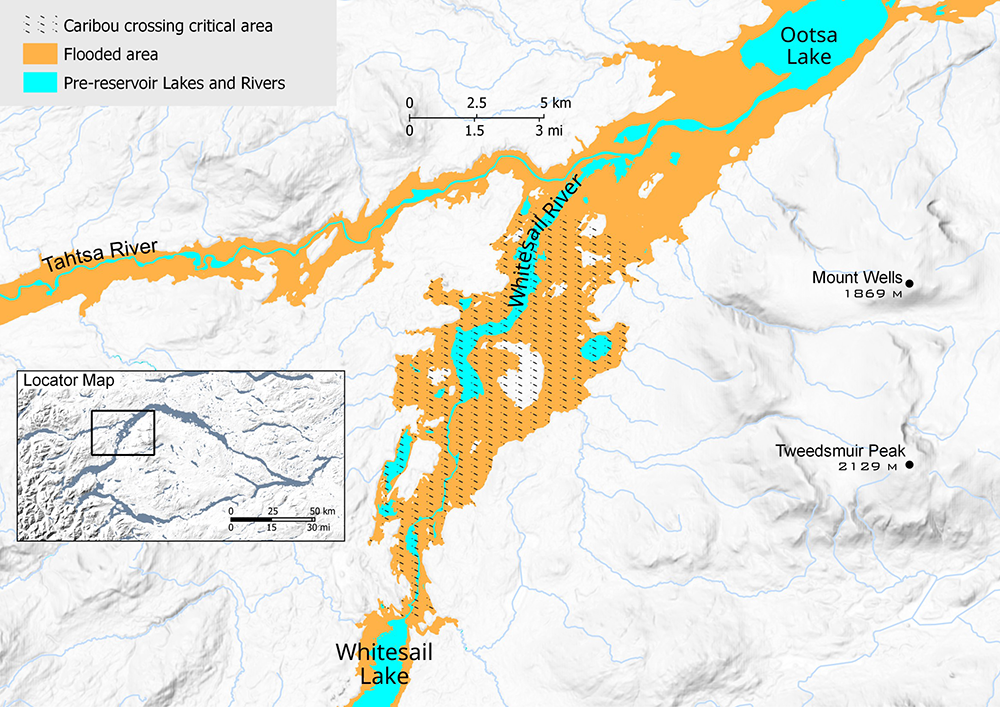

In particular, the flooding cut a path across migration routes used by the Tweedsmuir-Entiako caribou herd.

Like most caribou in B.C., the herd has seen dwindling numbers in recent decades. Estimates from the 1960s put it at about 600 animals. By the early 2000s, it was reduced to half that. A survey five years ago put the herd at 150 to 180 caribou, according to a report by the B.C. government.

But the trend appears to be shifting. For the past five years, Cheslatta and the provincial government have been working together to restore caribou habitat and examine whether some reservoir impacts can be reversed. The most recent survey of herd numbers, conducted this spring, indicates the efforts are helping.

Today, like all caribou in the southern two-thirds of the province, the Tweedsmuir-Entiako herd is listed as “threatened” under both Canada’s Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife and the federal Species at Risk Act. Provincially, it is blue-listed, making it a species of “special concern.”

Like the loss of salmon and Nechako white sturgeon downstream of the Kenney Dam, it’s impossible to identify a single reason for the caribou’s decline. But industry and other human impacts play a significant role.

Predation from wolves is also a primary cause, as the roads pushed through for industry make it easier for the carnivores to move into caribou territory. Mining and logging have had an impact on habitat, as have the effects of climate change, like increased wildfire activity and blowdown due to the mountain pine beetle epidemic.

The reservoir has also played its part, according to the province’s report.

“The construction of the Kenney Dam in the 1950s and the subsequent formation of the Nechako Reservoir may have contributed to the abandonment of winter ranges to the north of the Whitesail and Ootsa portions of the Nechako Reservoir,” it says. “The higher waters also flooded islands that may have been used as secure calving locations.”

The caribou’s federal “threatened” status obligates the provincial government to make species recovery a priority.

The province recently wrapped up a five-year habitat restoration project that saw remote resource roads — most of them in the eastern portion of the reservoir where the Tweedsmuir-Entiako herd spends its winters — returned to a more natural state.

Over the course of the project, D’Andrea — who spent decades working with the province before making the leap to working with the nation as a contractor earlier this year — says Cheslatta Carrier Nation moved from a supporting role into planning and implementation.

“People were coming to Cheslatta with a plan and saying, ‘What do you think of the plan?’ Cheslatta’s now developing the plan, in conjunction with the province,” he says. “There’s things Cheslatta can bring to the table and there’s things that the province can bring to the table.”

As the nation works with the province on its next five-year plan, D’Andrea says there is endless opportunity, and no shortage of work implementing the myriad contracts Cheslatta has been forming with both industry and government.

“There’s so many amazing projects that can be done within Cheslatta territory. There’s so much support for it, from the province, from Rio Tinto, from Cheslatta,” he says. “I think that the next 30 years are very, very bright for Cheslatta — and not just for Cheslatta, for the land in this area.”

Hilltops, not islands

In mid-September, I teeter on a log, imagining I’m a caribou.

I rolled out of bed at 5:30 a.m., the temperature hovering just above freezing and mist rising from the water at Takysie Lake Resort as I rushed to meet a team from the Cheslatta Carrier Nation and the provincial government heading out on the reservoir.

They are here to check remote trail cameras. The motion-sensor cameras provide a rare glimpse into the world of wildlife that pass through Whitesail Reach, in the northwest corner of the reservoir.

By the time we launched the boat, the sun was just peeking over the horizon. We won’t return for more than 10 hours, just as it sets. There are about 40 cameras to check and access for most is challenging.

As I pick my way along the logs, I try to imagine the gangly, hooved caribou — many of them just months old — navigating their smooth, sun-bleached surface. The timber is stacked at least a metre deep, like a giant game of pick-up-sticks. Following one log, then another, I tack and jib in the general direction of a wildlife camera strapped to a tree, following Anne-Marie Roberts, a wildlife ecologist with B.C.’s Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship.

“It’s about 100 metres,” Roberts says about the distance from the boat to the camera. “But it will feel more like 500.”

Ask anyone about Tweedsmuir-Entiako caribou, and they will direct you to Roberts. She joined the province in 2015 to lead monitoring of the herd following the Chelaslie River wildfire, which burned through the caribou’s winter range a year earlier, destroying more than 100,000 hectares.

In 2019, Roberts started the camera monitoring program. She captured her first images of caribou that spring, not far from where we’re standing, including pregnant caribou. “Something simple like that was just really powerful reinforcement that, yes, you are standing in caribou calving habitat.”

When they returned to check the cameras later that season, they found photos of newborn caribou, just taking their first, wobbly steps at the same location.

The Tweedsmuir-Entiako herd has the longest migration route of any in the province. It leaves its winter foraging grounds in the eastern part of the reservoir every April and travels roughly 120 kilometres west, through North Tweedsmuir Provincial Park, to get to its calving grounds at Whitesail Reach.

When the caribou arrive, they hit a barrier.

As the chain of lakes that formed the reservoir flooded, it widened most significantly here. Once a river connecting Whitesail Lake to Ootsa Lake, the 20-kilometre-long corridor is now several kilometres wide and the flooding left heights of land, those preferred by calving caribou, surrounded by water.

Hilltops. Not islands.

The widened waterway likely contributed to the herd abandoning its range northwest of the reservoir, according to a caribou restoration plan prepared for the province in 2020.

But it also presents an opportunity: The water surrounding high-elevation calving grounds provides additional protection to female caribou and their young.

If they can get there.

While caribou are strong swimmers — giving them an advantage in the water over wolves that can easily outpace the hooved animals on land — the logs that choke the shoreline make getting into or out of the reservoir a challenge. It means that caribou can make a kilometres-long swim, only to find themselves unable to access the shoreline on the other side.

It’s something that’s noted in the province’s recovery plan, with woody debris that collects along shorelines contributing to caribou deaths.

“Currently, log debris along the Nechako Reservoir may affect the ability of caribou to access shorelines while crossing the lake,” the plan notes.

As a result, Whitesail Reach is identified as one of three “priority restoration areas” in the province’s plan to recover the herd. It is the only priority area in its summer range, which it uses from May until late October or early November. The other priority areas lie to the southeast, in winter habitat impacted by roads and scarred by wildfire.

The goal at Whitesail is “to reduce large woody debris along shorelines of calving islands and the mainland that are used by caribou during migration and for accessing calving islands,” the restoration plan says.

Clearing the way

In 2019, after the Tweedsmuir-Entiako herd had moved south for the winter, the Cheslatta-B.C. team undertook a pilot project to remove debris from a 500-metre stretch of shoreline at a popular caribou calving spot in the hopes of facilitating access.

While temporarily successful, the stretch of shoreline has since filled in with woody debris. The reality is that the wood could be cleared away and continue to accumulate for decades to come. But it’s hoped that research and careful planning could help direct resources where they will have the most impact, both Cheslatta and the province say.

“We learned a lot from that project,” Roberts says. “One of the things that I’m monitoring is the legacy of that. Is it just going to get blown in with more wood and how fast does that happen? Because if we are looking to invest in additional shoreline treatments, we want to make sure that there’s a longevity to that investment.”

The work currently underway, which includes radio collaring in addition to cameras, will help the researchers understand migration routes in order to focus on clearing pathways that the animals are most likely to use. The plan also calls for monitoring, which is why the team is here collecting images from the cameras positioned strategically around the reach.

The cameras offer a site-specific glimpse into caribou habits at Whitesail, as well as capturing the movements of animals that aren’t collared with GPS devices.

Our route through the reach takes us in a circuit, skirting peaks to the southeast in Tweedsmuir Provincial Park and then along shorelines to the west. Roberts is joined by Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship ecosystems biologist Kindra Maricle and staff from Cheslatta Carrier Nation — William Elkins is with the nation’s Indigenous guardian program and Cody Reid navigates the boat from camera stop to camera stop.

Some are easy to reach. Most require clambering over logs or through the bush to locate — and a keen eye.

“I see it!” Dozens of metres from shore, Reid points to the camouflaged bear-proof case, a speck of green amidst the trees. He navigates the boat over and around floating logs, bringing the crew as close as possible.

On rare occasions, he’s able to nose right up to the camera. Most often, it’s not that easy. Where the logs aren’t beached, they form a dangerous floating mat that could swallow a person — or an animal — and trap them beneath the reservoir.

‘Not used or otherwise gainfully disposed of’

In 1950, Alcan and B.C. signed an agreement that gave the company control over the reservoir area in exchange for producing “low-cost electrical power” for the company’s aluminum smelter. It gave Alcan the rights to store and divert water and “to occupy all Crown Lands pertinent to the full development and operation” of the project under B.C.’s Water Act.

The agreement offered no provision for logging the flooded area, instead giving the company permission to “use or destroy” any timber within it, despite attempts by local mills to harvest the trees.

“No stumpage or royalty will be exacted on timber which is damaged, destroyed or removed in connection with the construction or operation of the structures and facilities enumerated in this section, and which is not used or otherwise gainfully disposed of by Alcan,” the agreement states.

In 1980, Cyril Shelford, who began a 20-year stint as MLA for the area the same year the reservoir flooded, recalled to the Smithers Interior News that he had tried to salvage some of the millions of board feet of timber before it was swamped by the reservoir.

“We had a small sawmill and we applied to the government to cut some of it near Andrew Bay,” Shelford told the local paper. “But they turned us down because it was parkland.”

As a result, most of the timber — about 10 million cubic metres, according to D’Andrea — remains, greyed and rotting, 70 years later. While the elements take their toll on trees that breach the reservoir’s surface, the wood that is completely submerged has been preserved.

It’s still useable lumber. But it’s difficult to access.

For a time, the Cheslatta, led by Rakochy, explored the feasibility of underwater logging, and for several years in the early 2000s operated a mill nearby. While there was sufficient timber beneath the reservoir to supply it for decades, the logging — which involved remote submarines, scuba divers and slinging the timber between two floating tanks — was complex and costly. As fuel prices rose in the late 2000s, the mill became uneconomical and eventually closed.

But the methods learned 20 years ago could be applied to clear migration routes in Whitesail. Rakochy speculates that timber prices may be rising to a point where underwater logging operations could become feasible again.

In 2016, B.C.’s Nadina Natural Resource District wrote a letter to the Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako requesting support for a “tentative” project that would create a “timber-free zone” in the Nechako Reservoir, focused on Whitesail Reach and its high-quality caribou calving habitat.

“This includes the removal of all submerged or partially submerged trees up to the reservoir high water mark, which will allow the region’s endangered woodland caribou to successfully move from islands in the reservoir to the mainland,” the letter says. “All natal activity associated with these caribou occurs on these islands, and the young calves swim across the reservoir to the mainland. At present, many of these young animals fall prey to obstacles created by submerged timber.”

While the regional district confirmed to The Tyee that it had written a letter supporting the project, to date the initiative has not gone ahead. It’s something the nation could consider as it outlines plans for the years ahead, D’Andrea says.

Cheslatta continues to operate its own forestry company and the nation’s experience in the industry provides an opportunity for workers to clear the way for caribou in Whitesail, he says — something that would both improve habitat and provide economic development.

“There has always been talk about firing up the underwater logging,” D’Andrea says. “This is an area that has a whole bunch of values that we want to look at, both aquatic and terrestrial… but it just hasn’t happened.”

As the water licence holder, Rio Tinto Alcan will need to be involved in the conversation. It’s something the company has expressed a willingness to support, and says it has in the past sponsored work through the Water Engagement Initiative to facilitate caribou access.

The relationship between the company and Cheslatta hasn’t always been a positive one. But that’s changing, the nation says.

“Rio Tinto listens. They’re concerned and the conversations that occur are very pragmatic,” D’Andrea says. “We haven’t actually sat down and said, ‘OK, what do we want to do for 2023?' If we were to focus on a migration route in the Whitesail, I think that’s a conversation that we could have between the province and ourselves and Rio Tinto.”

The reservoir provides no shortage of restoration projects, he adds.

“The next 30 years are going to be very exciting. I think the momentum is there, the understanding is there, from everyone sitting at the table,” he says. “I feel honoured to be part of the team to help keep those projects moving forward.”

A promising outlook

By late afternoon the team is down to its last few cameras. Late summer sun casts a golden light across the reservoir as Reid steers us into a bay and stops the boat some 30 metres offshore. What lies between us and the shoreline is an impenetrable blanket of floating logs.

The camera is among a handful that will have to wait for another day, likely in early spring when the crew can land a helicopter on the ice and safely walk in.

But amongst the thousands of photos downloaded today are rare glimpses into life on the reservoir when boats and biologists aren’t present. They include wolverines, otters, bears, moose, even a passing elk — rare in these parts.

And, of course, they include caribou.

The images will be reviewed in greater detail over the winter. But already Roberts has learned that the area is still being used by caribou, not just to give birth but to linger for the summer months. Other wildlife, like moose and bear, are here as well.

“We know calves are being born and we’ve had them spend the whole summer on that island,” Roberts says. “As we’re seeing the herd grow, hopefully on a pathway to population recovery, this is a part of what historically has been calving range and we want to be able to retain that behaviour.”

Early indications are the herd is indeed on a path to recovery.

Recent surveys of Tweedsmuir-Entiako caribou show the herd is “well in the growth zone,” Roberts says. A survey in 2017 showed it had increased by 55 per cent over a few years earlier. The most recent count, conducted this past March, indicates it is now more than 200 strong.

But perhaps most promising is the significant number of youngsters. About a quarter of the caribou counted were calves, significantly more than the proportion needed for a stable population.

“We are growing and it’s very exciting,” Roberts says.

A wildlife habitat area proposed for Whitesail and surrounding area will further protect the herd. It is being co-designed by the province and Cheslatta, with input from other First Nations, Roberts says.

As the crew makes its final stop, pausing to admire the image of a small grizzly bear dragging itself from the reservoir, the last memory card is carefully tucked into a case with dozens of others, preserving another chapter in the story of wildlife on the Nechako Reservoir.

The jetboat drowns out any possibility of conversation on the return boat ride. We sit in silence, the setting sun silhouetting ospreys in their lofty nests and highlighting the forested hills.

It’s easy to see how the area could indeed be a favourite place for both people and wildlife — and a place worth saving. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: