[Editor’s note: On Oct. 8, 1952, the Kenney Dam blocked the flow of water into the Nechako River, forming a massive reservoir and hydroelectric facility to create an aluminium industry. Seventy years later, The Tyee explores the lasting impacts of the Nechako Reservoir and work underway to restore some of its damage. First in a three-part series.]

In July, staff at Cheslatta Carrier Nation huddled around a conference table at the nation’s band office, a cluster of buildings a kilometre south of Francois Lake.

They leaned on the table's glossy surface, embedded with maps of the nation’s traditional territory. Black-and-white photographs of Elders adorned the walls, Cheslatta ancestors watching over them as they deliberated.

The staff were grappling with a threat to their effort to bring children in government care back to the territory and connect them with their people and culture.

The planned location — a former village site on Cheslatta Lake — was under several feet of water.

It’s a familiar problem for the Cheslatta Nation, which has faced 70 years of disruption and destruction since the B.C. government approved a massive dam that reversed most of the Nechako River’s flow and flooded almost 400 square kilometres of their territory.

Today no one lives at Indian Reserve No. 7, the planned gathering site. And none of the people around the table remembered a time it had been occupied.

Cheslatta were forced to abandon the traditional village site, known as Skatchola or simply “number 7,” in 1952 as water levels in the lake steadily rose due to construction on the project. They were pushed off with almost no notice or compensation, casualties in the B.C. government’s push to create an aluminum industry.

But they still have a deep connection to the place where their ancestors lived for thousands of years.

“That’s why it’s so nice to return home to number 7,” says Lana Macdonald, who works as a family advocate with the nation. “You instantly feel it when you go there and you’re walking along the shores, along the trees — you feel your ancestors there.”

Some of those ancestors look on from the conference room walls. They paddle dugout canoes, ride horses and pose with large families.

But more recent images on the walls show an aerial view of a washed-out river valley and flooded gravesites, their white crosses surrounded by water.

Seventy years after water first rose in Cheslatta Lake, the nation is still dealing with fallout from a massive hydroelectric project that changed the face of their territory. Graves, some thousands of years old, are submerged and traditional village sites underwater.

It’s something that’s occurring with increasing frequency, they say, with several “one-in-200-year” floods over the past decade. Each time, the deluge erodes more of their ancestors’ remains from the shoreline.

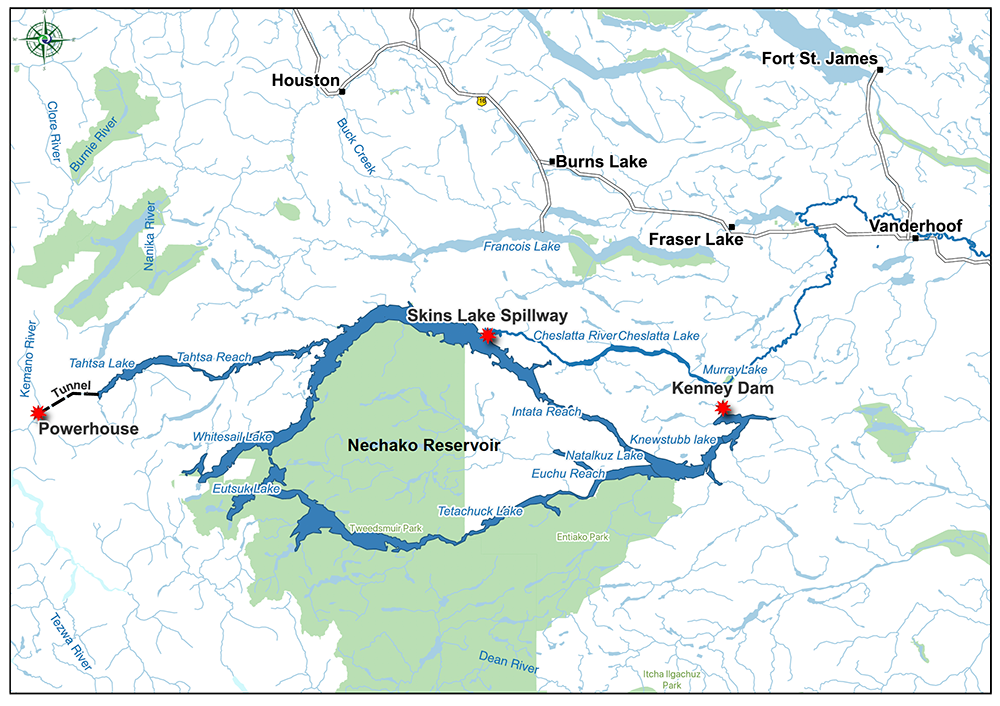

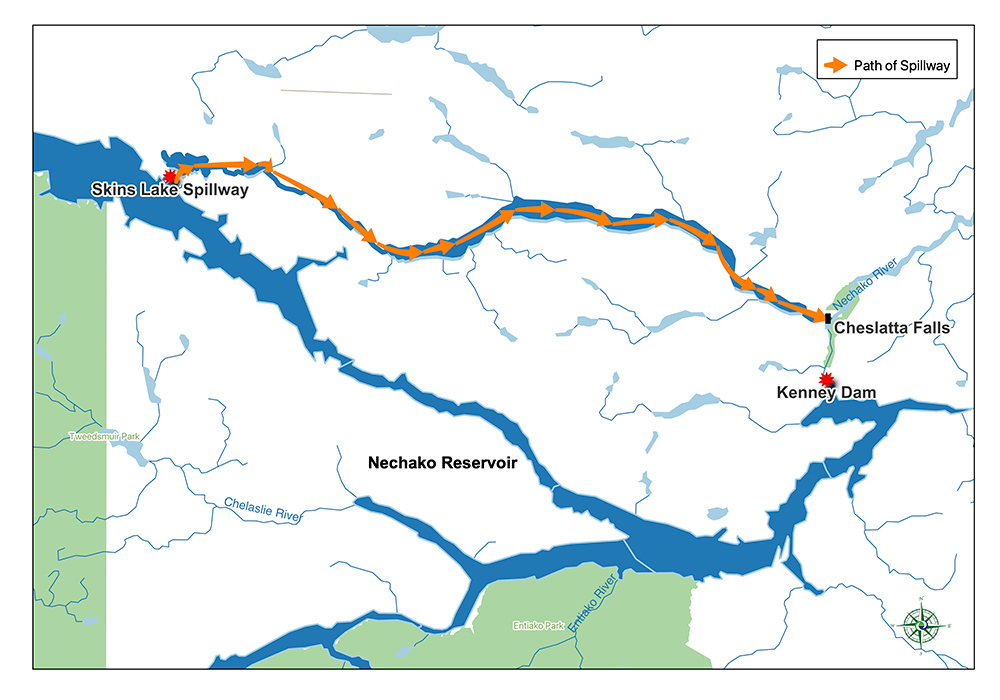

Cheslatta Lake forms part of an 80-kilometre-long corridor that drains the Nechako Reservoir. When high water levels threaten to exceed the reservoir’s authorized capacity — like this year, when a late freshet coincided with a wet spring — a rush of water is released through the system. Scouring riverbanks and eroding Cheslatta territory, it empties into the Nechako River eight kilometres downstream of the dam.

But today the nation of 360 people is slowly putting that history behind it and working to find resiliency from the tragedies of the past. A decades-long fight to curb the flooding that plagues the territory could soon yield a project that would not only bring relief from the environmental impacts of Kenney Dam, but also provide economic opportunity.

They’re hoping that government and industry will get on board.

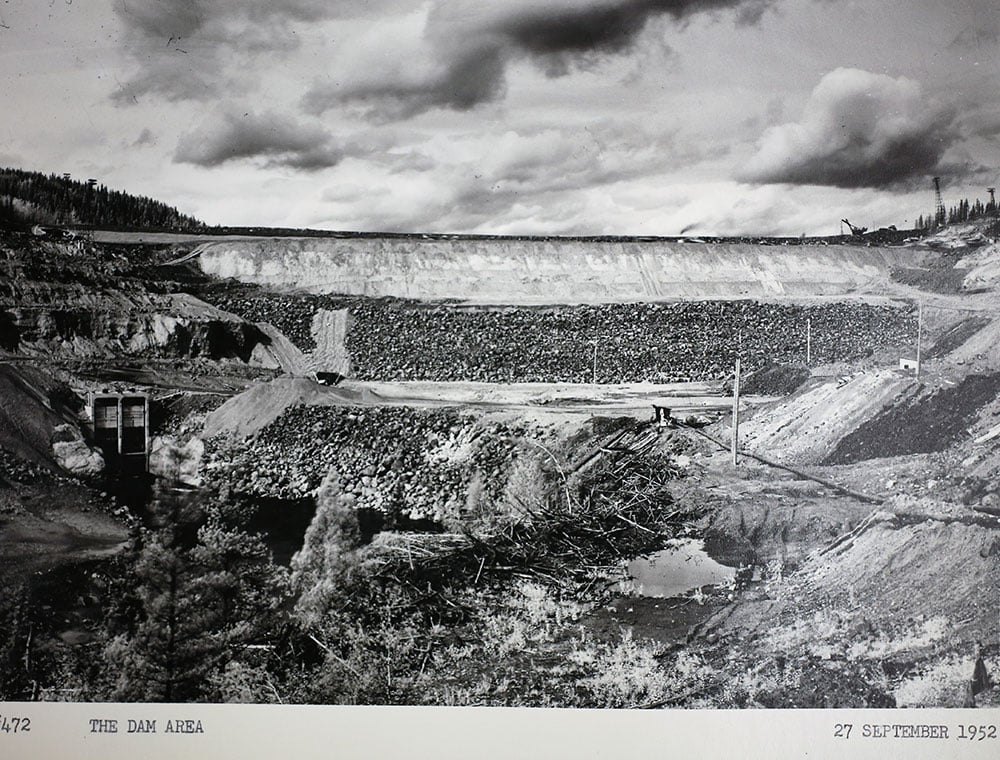

Water first began to rise in the Nechako Reservoir on Oct. 8, 1952. The Kenney Dam — the largest rockfill dam in the world at the time — was taking shape. The dam aimed to reverse the flow of the Nechako River, one of the Fraser’s largest tributaries, sending two-thirds of its volume back toward the north-central coast.

That would ultimately create a 900-square-kilometre reservoir more than twice the size of Okanagan Lake.

About 200 kilometres to the west, crews were drilling a 16-kilometre tunnel through the coast mountains to deliver water from the reservoir to the Kemano Powerhouse, an underground hydroelectric generating station that would power an aluminum smelter being built by the Aluminum Co. of Canada, or Alcan, in Kitimat.

The smelter opened in 1954. It took four years for the reservoir to fill.

As the water rose, it consumed a chain of lakes that lay between the dam and the generating station — Tahtsa, Whitesail and Ootsa lakes and others — consolidating them into B.C.’s second largest waterbody after the Williston Reservoir.

It consumed forests, leaving timber to rot and tumble into the reservoir, forming floating rafts of logs and debris that would clog bays and shorelines, blocking wildlife migration.

Rising water would flood dozens of settler homesteads and swallow up cabins, traplines and ancient village sites used by Cheslatta for millennia, burying a wealth of archeological knowledge.

But that wasn’t the only damage.

As Alcan prepared to shut off flows into the Nechako River, the federal government grew alarmed about potential impacts to salmon. During the years the reservoir filled, no water would be released through the spillway, an outlet located 80 kilometres west of the dam at Skins Lake.

The company planned to dam the Cheslatta River, a temporary arrangement that would provide water to be released seasonally into the Nechako River until the spillway was operational.

The result would be several years of flooding followed by torrential and erratic water releases that would tear at the riverbanks and carry silt downstream in the decades to come, damaging Cheslatta territory and clogging spawning beds used by salmon and white sturgeon with sediment.

‘It cost Cheslatta everything’

For as long as anyone can remember, Cheslatta people lived along the shores of a circuit of lakes east of the Coast Mountains.

When the first wave of smallpox swept through the region in 1838, village sites farther south, on Ootsa, Tetachuck and Eutsuk lakes, were abandoned. Those who survived — their numbers reduced from hundreds to about 50 people — joined other Cheslatta villages to the north at Cheslatta and Murray lakes.

They acquired horses, trapped and traded with settlers. The small nation of fewer than 100 people continued to thrive independently into the early 1950s.

Mike Robertson, senior policy advisor for the Cheslatta Carrier Nation, says Alcan’s decision to drain its reservoir through the spillway at Skins Lake, 80 kilometres west of Kenney Dam, where it would flow through the Cheslatta system, was made to save money.

“But it cost the Cheslatta everything,” he adds.

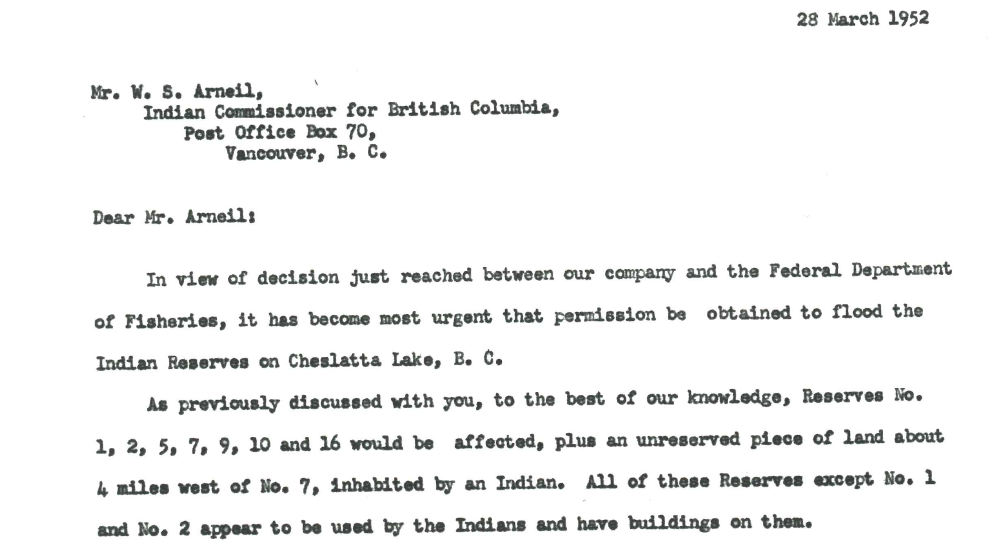

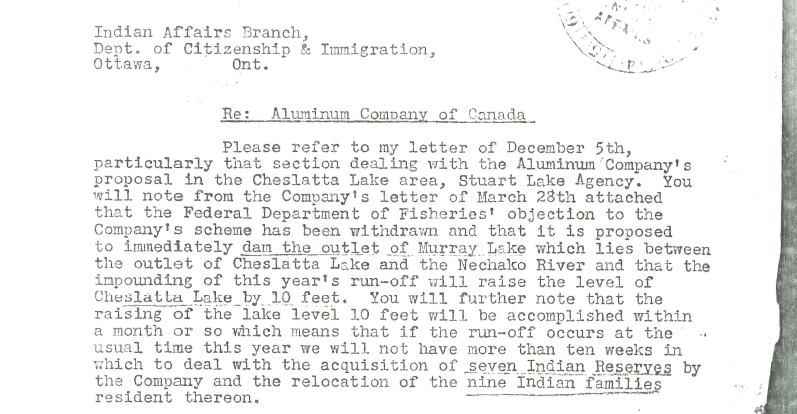

A series of telegrams from the spring of 1952 tells the story of how Cheslatta were forced from their land in a matter of weeks.

The first, sent March 29, 1952, from the Indian Agent in Vanderhoof to the project manager at Kenney Dam, relays the federal government’s instructions “to proceed to Cheslatta Lake and arrange for the evacuation of the Indian settlers around the lake at the earliest possible date.”

Five days later, Cheslatta was told of the plan. A “surrender meeting” was set for two weeks later.

On April 8, the water began to rise.

The following day, the Indian commissioner for B.C. sent a telegram to the Indian Affairs Branch in Ottawa, saying Alcan had deposited funds to cover the “cost of temporarily establishing nine families elsewhere.” It added that “insofar as is possible” it would also relocate graves that were below the flood line.

The Cheslatta maintain that the April 21 document selling their land to Alcan for $130,000 was forged by government officials desperate to remove them from the territory. It promised “the total cost of moving and re-establishment to be borne by the Aluminum Company of Canada.”

The next day, with the promise of new land, Cheslatta left their traditional village sites, most travelling two days to Grassy Plains and Uncha Lake, 60 kilometres to the northwest. Told they could return for the rest of their belongings, they took only what they could carry, leaving behind homes, tools and traditional regalia.

But when they returned later that summer, they found that Alcan had burned their homes and destroyed their property.

“Today, Cheslatta has no artifacts,” Robertson says.

Chief Corrina Leween blames the decades of spiralling trauma that followed on the loss of cultural identity.

Cheslatta were separated from their traditional hunting and trapping territories. Cycles of cultural knowledge transfer were disrupted. Children from the community were sent to Lejac Residential School, 80 kilometres to the east, and the Carrier dialect they spoke was almost entirely extinguished.

Leween’s mother and grandmother were among those who left Cheslatta Lake in April 1952. They settled in Burns Lake, 60 kilometres to the northwest, and her mother was sent to Lejac.

But she says the Elders didn’t talk much about their experience.

“I think it was protection for us children,” she says. “We weren’t taught our language. It was best not to because they were punished for speaking the language.”

Other families were pushed into Southside, the pastoral area stretching 40 kilometres between Francois and Ootsa lakes. They were forced to use their $130,000 payment from Alcan to buy scraps of land that private owners were willing to sell, often the least productive parcels.

The community found itself scattered.

“Back in the day, families visited, connected, helped each other,” says Tara Quaw, who works as the nation’s culture co-ordinator through Carrier Sekani Family Services. “We lost a lot. Our generation now, our ancestors being put into residential school, losing our traditions, losing our language. It’s heartbreaking. It’s hard to get that back.”

Cheslatta went from living an independent life on the territory to being dependent on government. When they asked for assistance to rebuild, the Indian Agent told them he couldn’t help — they were no longer living on reserve.

Robertson says 60 per cent of people who walked away from Cheslatta Lake in the spring of 1952 died unnatural deaths. In the years that followed, community members were lost to suicide, murder, car wrecks and overdoses.

When the water rises

Robertson gazes out over Upper Cheslatta Falls in full flood as water levels peak in midsummer. The water rushing through the canyon is more than 50 metres wide in places.

According to Cheslatta Elders, he says, there was a time when you could jump a horse across it.

Historically, water meandered through the Cheslatta system at about five to 10 cubic metres a second, he says. Today, we’re watching almost 400 cubic metres per second thunder through the canyon. The current continues to undercut banks, even 70 years later.

While Alcan eventually shored up the earth around the cemetery at number 7 in 1992, the remains of ancestors buried thousands of years ago continue to be exposed along the riverbanks and slide into the waters. One collection of burials, five individuals discovered last year at Cheslatta Lake, was dated to 4,600 years ago. Dozens more have washed away, Robertson says.

“It’s spectacular to look at and listen to, but it’s an industrial spillway,” Robertson says about the destruction wrought by the Cheslatta River.

But that could change, he says. “Kenney Dam release facility is going to turn it back into a waterway.”

Talk of putting an outlet in the Kenney Dam goes back decades. It’s believed that returning flows to the Nechako Canyon below the dam could benefit salmon by lowering water temperatures in the river, while reducing the impact on Cheslatta territory and providing economic opportunities for First Nations.

The discussions date back further than the dam itself. It was part of the original designs, but later scrapped.

The idea was resurrected in a 1987 settlement agreement between Alcan and the provincial and federal governments, which relinquished the company’s rights to expand the reservoir into the Nanika River and authorized it to “construct works for the protection or enhancement of the fisheries resources in the Nechako River” — a vague reference to a water-release facility in the dam.

It was revisited again, a decade later, as part of a 1997 agreement between B.C. and Alcan, when the company committed $50 million to establish the Nechako Environmental Enhancement Fund, money promised for environmental rehabilitation in the watershed.

That included examining “options that may be available for the downstream enhancement of the Nechako watershed area [including] the development of a water release facility at or near the Kenney Dam,” according to the deal.

But the facility never materialized.

In high water years it means that Rio Tinto, which merged with Alcan in 2007, is left with a delicate balancing act. Allow reservoir levels to get too low and risk losing power to the smelter; too high and be faced with releasing a torrent of water through Cheslatta territory.

It’s something the company tries to avoid, says Andrew Czornohalan, operations director at Rio Tinto BC Works.

“Typically, we don’t want to exceed 300 cubic metres per second through the spillway, because we’ve known that anything above that starts to impact the Cheslatta traditional territories, the Cheslatta gravesites and their culturally significant areas,” he says.

But at the same time, “in order to maintain the dam safety, I have to release the amount of water that’s coming in,” he adds.

The alternative is to request permission from B.C.’s Comptroller of Water Rights to exceed the reservoir’s limit, buying time in the hopes water levels will fall. Going above the reservoir’s “full pool” is something that has happened only a handful of times in the past 70 years, Czornohalan says.

He describes the “black magic” practised by the company’s hydrologists, who are continually projecting weather probabilities a year into the future — while also modelling 70 years of reservoir history.

It’s something that’s becoming more difficult as climate change makes weather patterns less predictable.

“We never know whether we’re standing on the precipice of the wettest sequences we’ve ever seen and imminent flooding, or if we’re standing on the first day of the worst drought that's ever been seen,” Czornohalan says.

The impact of losing power to the smelter, even for a few hours, is “catastrophic,” he says. The giant pots of molten aluminum would cool and solidify.

“It takes years to restart, the cost involved is enormous, the impact to employees is huge.”

The facility draws 700 megawatts, comparable to a city of a million people, Czornohalan says. It also provides 1,000 direct jobs in the region and $700 million a year in provincial revenue, he adds.

Surplus power produced by Kemano — about 20 per cent of the total — is sold to BC Hydro. Czornohalan says it forms an “integral part of the northern grid,” providing energy to around 250,000 residents.

In the early 2010s, according to BC Hydro’s financial statements, the provincial Crown corporation was paying Rio Tinto about $200 million a year to buy its surplus power. That number has dropped by about half since 2016 when the Kitimat modernization project began pulling more power to the smelter.

By comparison, documents filed during a B.C. Supreme Court case against Rio Tinto Alcan by downstream First Nations show the company paid, on average, less than $18 million annually to the province between 2008 and 2017 for the water it diverted from the Nechako River.

“Not a penny of that has ever come back to the communities,” Robertson says.

At least a portion, he suggests, could help fund a water-release facility at the Kenney Dam.

Underwater logging, paddles and partnerships

The shift in Cheslatta’s relationship with Alcan started with a load of firewood.

When James Rakochy left a job in forestry to join Cheslatta as its land and resources manager in 1999, things were still rocky. But he gradually got to know the Alcan employees operating the spillway.

One day, they asked if he could arrange a load of firewood for a nearby campground Alcan manages. It was the nation’s first contract with the company.

Since then, Cheslatta has looked for what Rakochy calls the “win-wins” — ways to improve the environment while also creating economic development.

Rakochy’s role initially was to explore the feasibility of logging timber left under the reservoir. The dead trees still stood tall, preserved for half a century by lack of oxygen. The process was complex, involving remote submarines, scuba divers and two floating tanks used to tow the timber to shore.

Because the water-soaked logs were too heavy to haul by truck, they needed to be milled onsite. In 2001, Cheslatta started a mill in Southside that employed 140 people and contributed nearly $1.5 million per month to the local economy. The vast timber resources beneath the reservoir were enough to power the mill for decades.

But it wasn’t enough to sustain the operation, which ran on a diesel generator.

In 2008, as fuel prices rose, the mill closed — ironically, because the nation was unable to secure the electrical power needed to run it.

It hasn’t discouraged Cheslatta from pursuing other unique economic development opportunities.

In 2002 the nation acquired a community forest and, after wildfires tore through the region in 2018, turned its attention to salvaging trees burned in the fires. For a time, it even ran a Chief Louie Paddle Co., which produced custom paddles crafted from local wood, some of it from beneath the reservoir.

The reservoir forms the northern boundary of Tweedsmuir Provincial Park and the nation has also found opportunity in recreation, taking over a wilderness resort on the territory and the operation of a motorized boat portage between Eutsuk and Whitesail lakes.

It operates a fleet of barges, tugs and jetboats, offering transportation on the reservoir to everyone from government biologists to industry workers.

Cheslatta’s partnerships with Rio Tinto Alcan have also grown since that first load of firewood.

The nation’s 2020 New Day Agreement with Rio Tinto laid the groundwork for more contracts, including an increased role at the Kemano power station and Rio Tinto’s recent “T2” project, which bored a second tunnel between the reservoir and the powerhouse.

Cheslatta now has the contract to operate the Skins Lake Spillway. It doesn’t give the nation control over reservoir levels, but does provide jobs.

“It’s a step,” Robertson says.

A new outlet for overflow

The most effective way to reduce the flooding’s impacts on Cheslatta territory, the nation says, is to go ahead with the long-called-for release facility at the Kenney Dam — something estimated to cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The exact cost would hinge on scope and design: Would it draw water from the bottom of the reservoir, better to cool the river below? Or would it skim it from the top, better for incorporating a hydroelectric generating station?

In a perfect world, it would combine all those things, Czornohalan says. Rio Tinto Alcan is currently undertaking a study that would examine the possibilities. It’s expected to be completed later this year.

After decades of pushing for the release facility at Kenney Dam, Chief Leween is hopeful the project may finally be on the horizon. She says the relationship with Rio Tinto has improved dramatically during her two decades as chief and she believes the right people are now sitting at the table.

“There’s a new atmosphere,” she says. “I’m really trying to be optimistic.”

Including the NeToo Hydropower Project would also provide economic development for First Nations in the region while reducing impacts on the landscape and returning flows to the Nechako Canyon. The idea first raised by Cheslatta is now championed by the First Nations Major Projects Coalition.

It checks a lot of boxes, Czornohalan agrees.

“That’s environmental, that’s cultural, archaeological — all of those interests that are currently impacted by the way water moves through that system,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be a win-and-loss mentality. I think there are genuine enhancements that are answering the need of multiple stakeholders.”

Of the $50 million promised by Rio Tinto Alcan’s 1997 agreement with the province, the majority — roughly $40 million — remains, waiting to be spent on projects that would rehabilitate the watershed.

But it requires matching funds. The question remains of who would fund the rest.

The B.C. government declined to be interviewed about the potential for a water release facility at the dam and did not respond directly to the question of whether it would consider funding it, instead saying in an email that “a release facility at the Kenney Dam would be the responsibility of the water licensee, Rio Tinto.”

It adds that moving ahead with the project would require the company to apply for a new or amended water licence and could require an environmental assessment.

In 2019, the province signed a Reconciliation and Settlement Agreement with Cheslatta Carrier Nation “to address the historic impacts of the Kenney Dam and Nechako Reservoir on the Cheslatta people.” It includes both financial compensation and land transfers over a 10-year period.

In 2012, Rio Tinto Alcan also returned 12,000 acres of land along the Cheslatta River. Amongst the parcels are the village sites sold by the province to Alcan in 1952 — including number 7.

But, as Robertson points out, their shorelines are unusable as long as erratic flows and flooding continue through the spillway.

Moving forward

On July 15, water peaked in the reservoir and began to subside. Months later, the levels remain high, but the risk to Cheslatta territory has diminished — at least for the time being.

By late August, number 7 was still too wet to hold a gathering. Instead, the nation welcomed its children back to the territory at the Skins Lake Spillway campground, the recreation site managed by Rio Tinto Alcan.

At the event, the company announced it would provide $2.8 million to fund an archeological excavation focusing on ancient village sites at Tetachuck Lake. The project will also recover human remains that have eroded from the banks of the Cheslatta River.

It’s funding that will begin to rebuild a vital link to the nation’s history, Leween says. She hopes there will be an opportunity next summer to take school children to the site and teach them about their ancestors. The nation has also developed an archive, a small but tidy room in the office buildings to safely store its cultural heritage, and programs are underway to bring back the language.

At the Cheslatta offices, there’s an air of excitement. Much of its current economic development allows the nation not just the opportunity to get out on the territory, but to heal the environment and undo some of the damage caused by the reservoir.

Leween says preserving what remains of Cheslatta history at places like number 7 and other ancient village sites are vital to returning a sense of identity to the nation.

“The key to resiliency is, first of all, just who Cheslatta people are, what they've been through and where they’re at now,” Leween says. “Given what has happened, I feel that Cheslatta people are just survivors, and they just keep fighting for what they believe is the right thing to do.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: