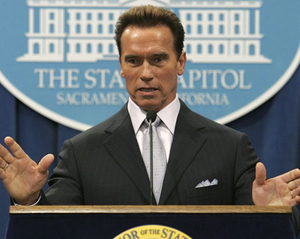

In late September, California's outgoing Republican governor declared all-out war on a fossil fuel cabal opposed to his state's landmark climate change laws. "They are creating a shell argument that they are doing this to protect jobs," declared Arnold Schwarzenegger to a crowd of several hundred at the Commonwealth Club in Santa Clara. "Does anybody really believe they are doing this out of the goodness of their black oil hearts -- spending millions and millions of dollars to save jobs?"

That proved to be the dominant narrative in the struggle over Proposition 23, an oil refiner-funded ballot initiative asking Californians to suspend some of the planet's most stringent global warming legislation. Hollywood itself couldn't have dreamed up a better story: a former action movie hero-turned-environmentalist doing battle with Texas-based oil magnates during the hottest year in recorded history. Green observers heralded the electoral defeat of Prop 23 this November as a clean energy triumph.

Yet one crucial plot point ignored by most onlookers may carry implications far beyond state lines. A key climate change policy now being implemented in California could someday wipe out huge profit margins for Alberta's greenhouse gas-intensive oil sands industry and the American refineries that depend on it.

A sophisticated lobbying effort led by Canadian officials, fossil fuel lobby groups and several of the world's largest oil companies is targeting policymakers and consumers across the United States.

On several fronts, it appears to be succeeding.

At stake: green regs in 24 states

The goal of this lobbying push is to defang a climate change policy being considered or adopted in 24 U.S. states. That policy, known as a low carbon fuel standard (LCFS), aims to clean up the fuel being pumped into cars, trucks and motorcycles. American drivers fill their tanks with energy from all over the globe. Though vehicle engines generally release the same amount of greenhouse gases no matter what they're combusting, some fuels have much higher carbon footprints than others.

In Alberta's oil sands, a thick substance called bitumen is clawed or steamed from the frigid northern muskeg, then cooked at high temperatures and diluted with chemicals. By the time the fuel is dripping from a gas station nozzle, it's already been responsible for 82 per cent more greenhouse gas emissions than, for instance, smooth-flowing light crude from Texas, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates.

The intent of a low carbon fuel standard is to set clear limits on these types of emissions, and then let the free market figure out the rest.

"What makes me excited about an LCFS is that it lets all fuels compete," said Peter Taglia, a scientist helping to develop a regional standard for 10 Midwestern states. "You're not picking a technology winner"

Schwarzenegger's gambit

But as The Tyee first reported this summer, a dense network of Alberta oil sands producers connected to U.S. refineries by pipeline sees a blatant attack on its bottom line. With active support from the Canadian government, it's been targeting American climate policies from coast to coast.

In early 2007, the world's first low carbon fuel standard was signed into existence by Arnold Schwarzenegger. "Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions pose a serious threat to the health of California's citizens and the quality of the environment," read the executive order's opening words. Legislation proposed a 10 per cent carbon emissions cut by 2020 across the entire road fuel sector. Regulators would track all the different fuels entering the state and assign a carbon footprint to each one. It was expected that suppliers, in order to meet emissions targets, would avoid fuels from Alberta's oil sands and other high-carbon sources. Market pressures, meanwhile, could induce major investments in clean energy.

The Canadian government intervened formally at least five times in the policy's development, citing a wide range of oil sands-related concerns, according to a recent Climate Action Network Canada report. And oil industry resistance was fierce, even after California officially approved its low-carbon fuel standard last January.

Two fossil fuel lobby groups and a national trucking association are currently suing to repeal it, arguing the policy would "harm our nation's energy security by discouraging the use of Canadian crude oil."

If the oil-refiner funded Prop 23 had passed in early November, it would have suspended low carbon fuel standard legislation along with other state climate policies, earlier Tyee reporting explained. "Because that proposition failed by about a 6 to 4 ratio, we assume that those climate change provisions are in effect," Iris Evans, Alberta's minister of international and intergovernmental relations, told the provincial legislature the day after its defeat. "We'll still have a lot of work to do on low carbon fuel standards."

Domino effect?

Given that fuel from the Alberta oil sands powers only a tiny percentage of California's vehicles, why so much opposition?

In Nov. 2007, about 11 months after California first proposed its low carbon fuel standard, 10 Midwestern states began considering a regional policy. The next year, looking explicitly at California's model, 11 northeastern and mid-Atlantic states did the same.

Low carbon fuel standard frameworks being developed right now could soon regulate 50 per cent of America's transportation fuel market, a recent Ceres-RiskMetrics Group report concluded.

But the real nightmare scenario for Canada's oil sands industry is the pressure that would put on the U.S. Congress to enact national laws.

Though Alberta has the second largest known oil reserves on Earth, it sells exclusively to American markets. A federal low carbon fuel standard, as the Ceres-RiskMetrics report argues, could potentially reduce U.S. oil sands demand a full one-third by 2030.

And that's assuming industry players invest billions of dollars to reduce their carbon output, purchase carbon offsets and blend their products with renewable fuels.

"In the unlikely event that no options were available for Canadian oil sands producers to comply with the LCFS," the report reads, "the U.S. transportation market could conceivably disappear."

"There’s a lot of 'ifs' in there," co-author Doug Cogan told The Tyee, insisting that a global decline in oil supplies combined with escalating demand still plays very much in Canada's favour. "But the fact that these scenarios exist is what drives [the Canadians] to go to California and to say 'this could have real implications for the growth of our industry.'"

Tomorrow, part two: Inside the expensive public relations campaign to win American citizens' support for oil sands crude. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Labour + Industry, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: