Your lungs will fill with beany steam as you step into the hot, humid tofu factory.

Peter Joe and his 88-year-old father Leslie look a bit like scientists as they don their boots, hooded nets and white coats. Peter leads him through the thick jungle of control panels and conveyer belts, but very soon it’s his dad who’s charging ahead.

Everyone looks up to say hello, from the quality inspectors to the power engineers tinkering with the tofu-making machines to make sure they’re running as smooth as soy milk. Leslie makes a detour, sneaking into the room where tofu is deep fried, and pinches a few hot puffs from the cooling rack.

Here on Vancouver’s Powell Street, at the edge of Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside, is the oldest of three Canadian facilities where Sunrise Soya Foods makes their tofu.

All their products start with soybeans, which are soaked in giant tanks. Then, they go into the grinder. The resulting slurry is cooked and the fibrous pulp is separated from the soy “milk,” the liquid. Calcium sulphate is added to the milk to help it coagulate. Silken tofu is left to coagulate as-is, but for firm tofu, curds are poured into a mould and pressed. The more strength applied to squeeze the liquid out, the firmer the tofu. The finished slab is cut and placed into water to be cooled — where Leslie plucks a smooth block out of the bath and holds it lovingly in his hand.

It’s been 67 years since he made his first block of tofu and 40 years since Peter helped open this Powell Street production facility in 1983. They’re here alongside other time-honoured brands in and around Chinatown that are still dishing out fresh, packaged products — among them are Hon’s noodles, Dollar Meat’s sausages, Kam Wai’s sticky rice joong — all of which supply supermarket fridges throughout the region and beyond.

Leslie has eaten a lot of tofu in that time. Still, he remains wide-eyed at the volume coming off of the production lines. It’s been a long journey for the family.

“We used to make tofu seven days a week at the back of our grocery store — all by hand,” he said in Cantonese.

As Leslie pops a tofu puff into his mouth, he and Peter share the Sunrise story.

Soy central

Come take over my tofu shop.

Leslie received the message from his ailing uncle in Vancouver when he was working at a restaurant in Medicine Hat, Alberta. It was 1956 and he hadn’t been in Canada long. He had only arrived from Panyu, just outside of Guangzhou, the year before at age 21. Nonetheless, Leslie made the move.

Leslie’s uncle had learned the craft from another Chinese immigrant who had spent some time selling tofu in Montreal — surprisingly, to warm reception — before opening a shop in Vancouver called Paris Tofu. During the Second World War, when Paris Tofu couldn’t get shipments of calcium sulphate from China, they burned plaster of paris until it was food-grade and used it as the coagulant.

Leslie’s uncle eventually opened his own shop called Nam Kee, which he wanted to pass on to his nephew. But he died before he could teach Leslie how to work with soybeans.

Nam Kee’s other tofu maker ended up teaching Leslie the tofu trade. For a fresh start, he renamed the business to Sunrise and gave himself the English name Leslie. It sounded British and he wanted to fit into Canadian life.

Sunrise made about 200 tofu blocks a day, selling them for a nickel each. The soy pulp was sold to pig farmers for feed, just like how the Japanese Canadian tofu makers, who called it okara, used to do.

“But the business didn’t do very well in the beginning,” said Leslie, who only made $10 a day, about $110 in today’s currency.

It was a tough time for tofu. Just over a decade earlier, this part of the city was a thriving centre for all things soy.

Sunrise was at 378 Powell Street, in the middle of what was Vancouver’s Japantown until the federal government forcibly displaced and incarcerated Japanese Canadians in 1942.

Early Chinese and Japanese migrants to North America likely made tofu as early as the 1860s, according to The Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America. In about every Japanese community on the continent, there was at least one tofu shop.

Vancouverites doing the shopping were lucky enough to have multiple options, considering Japantown was a large community with almost 600 businesses. Main Street had the Chiba Toufu-ya, Gore Avenue had the Miyazaki Toufu-mise and Powell Street had the Wakahayashi Tofu-ya and the Tanaka Tofu-ya.

The Tanaka family had been making tofu as early as the 1900s, with 3 a.m. starts and the youth in the family making deliveries, running up the stairs of rooming houses carrying tofu packaged in parchment paper, branded with the family stamp, and bundled up in newspaper. Also on Powell Street were the Amano brothers, who made soy products like miso and shoyu.

The internment swept all of this away.

Tofu with a side of veggies

To keep the tofu business going, Leslie decided to tack on another enterprise: “Why not sell produce too?”

Sunrise was in the right neighbourhood for him to have the first pick of the day; Chinatown, with many warehouses at its edge, was a hub for urban produce. Malkin Avenue has since become known as the city’s “Produce Row.”

As Leslie brought fresh fruits and vegetables to be sold at the front of the store, business took off. Earnings rose to $200 a day and he saved enough to pay his uncle’s widow in China to buy the business for $2,200.

Sunrise would become even more of a family affair. Leslie was introduced to his wife Susan, who joined him in the tofu business. In 1959, their son Peter was born, followed by three daughters: Sally, Winnie and Jenny.

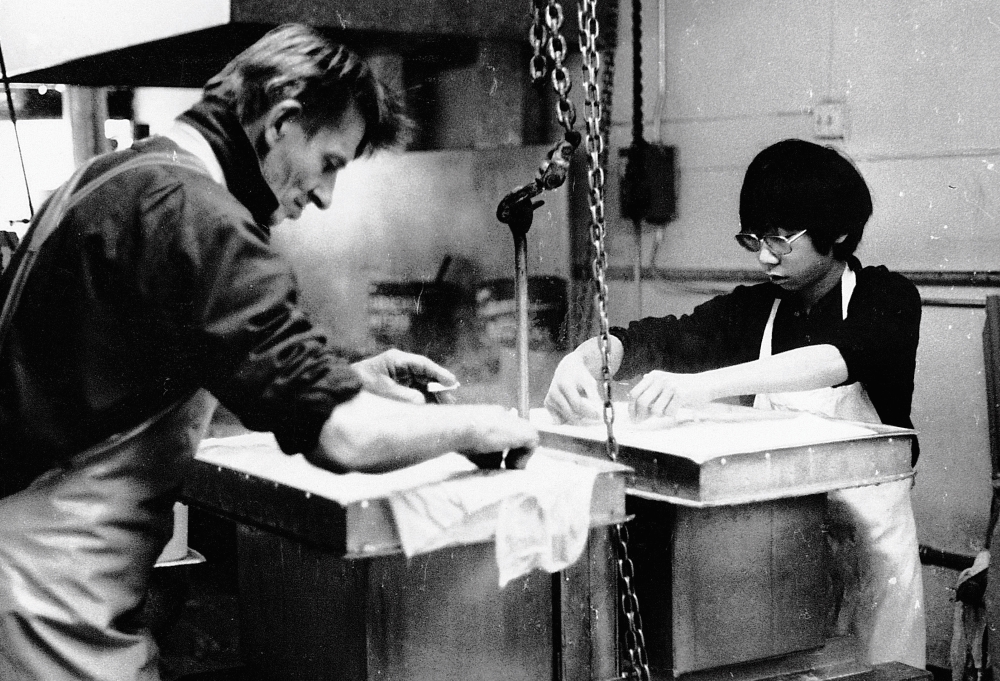

In 1961, the Joes moved to a bigger space at 300 Powell, continuing to sell produce at the front and bring tofu to life from Ontarian beans at the back: soaking, mashing, steaming, curdling and pressing. They bought a house a block away on Main Street, but life was mainly at the store, says Peter.

“We were born and raised in the business,” he said. “We were helping out when we were very young, rather than going to daycare or be babysat at home.”

Was it “forced labour”? Peter muses with a chuckle. Maybe, but it was also the typical story of other children of immigrant families in the neighbourhood, helping their parents to pay the bills.

At a young age, Peter made tofu and delivered it in Chinatown by cart and rode along with other employees in their vehicles. The tofu was kept in buckets and bus pans filled with water to prevent them from drying out. Vancouver is known for rain, but delivering tofu in that day and age meant always getting wet.

“You couldn’t help it. You’d always get water on your pants and shoes,” said Leslie, who’d look a bit like a fishmonger when making tofu with his waterproof apron.

The tofu machine

Peter came of age during a booming Chinatown in the 1970s.

“I experienced the whole vibrancy of the area at the time, knowing all the restaurants and shops,” he said. “Tofu being a fresh product, it’s made daily. On busy days, we’re talking multiple deliveries, not just once a day. And it’s heavy because of the water.”

It was then that he also caught a glimpse of tofu’s possibilities. Vegetarianism was taking off among those with western palates. One of Sunrise’s first non-Asian customers being Lifestream Natural Foods on Fourth Avenue in Kitsilano, the centre of Vancouver hippiedom. And for those concerned about eating local, tofu was attractive as a locally made product that used Canadian soybeans.

So when Peter graduated from business school at the University of British Columbia, he knew there was a job waiting for him. Peter recognized the privilege and opportunity of his university degree. In China, his father only had about four years of schooling.

“Making tofu is hard work. It’s hot and cold, it’s hands-on food manufacturing,” said Peter, thinking of his family toiling at the back of their supermarket. “Taking marketing in school put my mindset into thinking that this is a business opportunity I could spend my life doing, to help the family business, to help Dad and Mom. I went to Japan to take a look at how tofu can be made in a more automated way, so we took a risk.”

In 1984, with a million-dollar bank loan in hand, they purchased tofu-making machines from Japan and opened an industrial facility four blocks down from the family supermarket.

“My dad was very tough to have the courage and entrepreneurial spirit to make that investment,” said Peter.

When they ran the machine for the first time, everything changed. Daily production increased tenfold. The tofu’s shelf life jumped from three days to 28.

“We only used it like twice a week!” said Peter. “It was too big. But that really put the pressure on me. I had to go out and sell it.”

Soy ambassadors

While Chinese and Japanese communities in Canada were used to having soy production in their neighbourhoods, Peter and his sisters took on a new role as cultural ambassadors as part of the generation born and raised in the country. They tried to come up with creative new ways to introduce tofu in all its forms to eaters who never had it in their kitchens.

There was a phone-in “bean line” with a new tofu recipe every week. There was a tofu club, with a quarterly newsletter and recipe pamphlets for four dollars a year. There was a cookbook that taught you how to substitute tofu for a variety of dishes: banana cream pie without cream, garlic steak without steak, cheesecake without cheese. There were even tofu socials in local restaurants.

As Asian supermarkets stocked Sunrise’s tofu, western ones began carrying it too to attract Chinese customers, stocking it alongside noodles and bean sprouts. But Sunrise worked hard to break out of the cultural market.

“We tried to come up with new things every year. Fancier packaging, new flavours, different textures.”

There was a Sunrise line in Peter’s name. Called Pete’s Tofu, it came in flavours like Italian herb, “Great Crumbled in Pastas and On Pizza!,” and ready-to-eat snacks called Tofu 2 Go, in flavours like lemon pepper with mango chipotle. Their tofu pudding tubes, called Super Squeezies, won a Retail Council of Canada Award for best new product.

Peter had grown up delivering Sunrise’s tofu across the city. By 2002, he brought production to the east with the opening of a new Toronto facility. Then in 2019, Sunrise opened the largest of its three facilities in Delta, B.C.

But there was still work to do getting it into people’s shopping baskets.

More than ‘hippie food’

Tofu might have been a ubiquitous East and Southeast Asian staple for over two millennia — served grilled, deep fried, stuffed, in soups, in sauces, among a myriad of other ways — but white North Americans approached it with stigma or confusion when migrants introduced it over a century ago.

In 1917, a doctor and nutrition expert sent by the U.S. government to China to study the soybean told the New York Times that “Americans do not know how to use the soybean. It must be made attractive or they will not take to it” — exactly the kind of work that tofu makers like Sunrise are still doing. The author of the Magic Bean shared how tofu struggled in the west to shed a reputation of being “weird.” While the natural foods movement helped it gain recognition, it also burdened with the label of being “hippie food.”

In recent years, Sunrise mostly produces traditional classics, though some modern varieties have stuck around in their product line, like peach mango tofu dessert.

But education and experimentation are still on Peter’s mind. He continues to run recipes on Sunrise’s website to take tofu appeal to global palates. How about tofu “hummus”? Pulled tofu sliders with apple coleslaw? Jerk tofu with rice and peas?

Familiarity, innovation and trends all have a part to play in the continued mainstreaming of tofu in Canada, but the bean itself is doing well.

The soybean has been growing in the country for over 70 years and has become Canada’s third largest field crop. In 2020, farmers produced about 6.4 million tonnes, earning over $2.5 billion.

The new bean scene

The landscape of soy in Vancouver is a lot different these days from when Leslie had trouble selling his tofu.

As Taiwanese immigration increased in the late 1980s, they brought dry tofu in dark stocks, a common side dish. Then Korean newcomers opened supermarkets that stocked Californian brands and restaurants that served sundubu-jjigae soft tofu stews. In Richmond, you can find dessert tofu made Hong Kong-style, served with toppings like black sesame paste. On Vancouver’s Fraser Street, you’ll find a Filipino variation called taho, served with sago pearls in syrup. In the so-called western Canadian mainstream, soy has made its way into lattes and plant-based patties. And while Sunrise is the biggest brand for soy products, you can still find local shops here and there making fresh tofu for smaller markets.

Meanwhile, Leslie — as Peter expanded Sunrise nationally — kept busy too, expanding locally.

With all the Chinese newcomers in the decades after he touched down in Victoria in 1955, Leslie hired some of them at Sunrise, eventually partnering with a few to start their own supermarkets.

His three nephews and niece were among them. “My brother couldn’t make it to Canada, but his children did,” said Leslie, who helped them set up Vancouver’s beloved Donald's Market, which is still in the Hastings-Sunrise neighbourhood.

It’s a nod to the uncle who invited him to learn about tofu all those years ago, with older cohorts of immigrants helping the new ones.

Leslie has become a familiar face after spending seven decades in and around Chinatown, from Malkin Avenue’s Produce Row to his Powell Street supermarket.

He still makes a daily visits to Sunrise Market, where his three daughters run daily operations. They’re conscious about keeping prices low for Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside’s low-income customers.

“At my age, I have to keep my hands moving,” said Leslie on a January morning as he arranged cabbages in the shop. “I still like to fiddle with the display: keep the freshest produce in front, take the older stuff out.”

When the senior shoppers at Sunrise spot Leslie at work, they say in Cantonese, “Good morning, boss!” The Lunar New Year is approaching and a woman who has known him for decades wishes him youth and good health. But the sprightly Leslie doesn’t seem to need it.

“You know, I’m 88,” he tells her.

“Wow. You look so good.”

Leslie’s daughter Sally is here to greet him, having woken up in time to pick the best from Produce Row at 6 a.m., wearing an apron as she unpacks greens from cardboard boxes.

Four blocks down at Sunrise’s head office, her brother Peter is not in an apron but a collared shirt, doing a very different kind of work. He’s firing off emails on his laptop in-between non-stop calls on his cellphone.

In his travels, Peter has come across soy producers like Sunrise before they scaled up, serving their own corner of the world. They were families too, employing their children and extended relatives as a vehicle for livelihood.

It was a reflection of how far they had come. But Sunrise, having expanded, has its own share of challenges too.

“It’s always changing,” said Peter.

Take soybeans, for example. The crop could be better or worse than the year before. But the tofu they make has to be just as good.

“Tofu is still a very low-value product. It’s perishable. It’s not super expensive. So you gotta stay on top, you gotta maintain your quality.”

The business is ever growing, but the eventual goal is written on the wall of Sunrise’s boardroom: “Tofu in every fridge in Canada.”

At least Dad no longer has to work so hard with his hands.

Leslie loves to swim, play ping pong and rearrange the produce displays at Sunrise. But he also attributes his youthful vibrancy to his diet.

“I still drink soy milk every day.”

Part three: A Vietnamese refugee sells beef balls out of her apartment in an East Vancouver housing project to others who miss the taste of home. ![]()

Read more: Food, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: