I spent most of my preschool years at my grandparents’ house in Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province. It’s a city in southeastern China known for its historical significance and architectural buildings. To this day, the years we spent together are my most cherished memories.

In the morning, I would wake up at the break of dawn and head to the nearest farmer’s market with my grandma to pick up fresh vegetables and meat. I’d sing the whole way home as we held hands. My grandpa always kept me entertained. An expert in storytelling, he would tell fascinating Chinese fairy tales, switching voices for each character and moving his body to animate the story.

Most of the time, I stayed in my grandma’s kitchen, watching her make some of my favourite foods — braised pork belly with quail eggs, white cut chicken or fried rice noodles. There’s a special dish that I remember from that time and which she still makes only once a year around the time of the Dragon Boat Festival, which is today. The dish is zongzi.

Pronounced “joongzi” and also known as sticky rice dumplings or rice wraps, zongzi are made with glutinous rice stuffed with different fillings and wrapped in bamboo leaves.

My grandma is 86-years-old now. She started to prepare for this year’s Dragon Boat Festival earlier this week as she showed me a tightly wrapped zongzi while we were video-chatting on WeChat.

“Come back home and I’ll make some zongzi for you!” she said in Mandarin, “You used to love eating savoury zongzi when you were little until your tummy grew into a balloon.”

Watching her making zongzi half a world away through my phone screen made me feel connected with my grandparents, my childhood and my culture again.

The original fast food

Chinese dishes often have stories attached that have been passed down through generations. The origin of zongzi can be traced back to 771 to 476 BC, and it was first used as a sacrifice to ancestors and gods since animals were too expensive. Some historians believed zongzi was an original fast food for farmers who work in the fields and needed a quick meal that was easy to carry.

The story best known in China has it that the Dragon Boat Festival is to commemorate Qu Yuan, a poet and politician who lived during the Warring States period (340 to 278 BC) of Ancient China. Qu Yuan was known for his intelligence, patriotism and selflessness.

After being exiled by the king, he witnessed the downfall of his home but couldn’t do anything to help his people. He was so desperate that he decided to drown himself in the river. Local people who admired Qu Yuan raced out in their boats in an attempt to save him, but it was too late. They brought zongzi and cast them into the river, hoping that the fishes would eat the zongzi instead of Qu Yuan’s body.

Today, the Dragon Boat Festival is celebrated in many countries by holding boat racing contests, such as Vancouver’s Concord Pacific Dragon Boat Festival, and eating zongzi, which has grown into a varied cuisine of its own.

People in different provinces and regions of China have their preferences for zongzi, with northerners enjoying sweet zongzi with red bean paste, or plain zongzi dipped in sugar. In southern China, you’ll find zongzi with pork belly, salted egg yolk and mushrooms — ingredients that enhance the umami flavour.

In Vancouver’s Chinatown, there’s a dim sum place that could satisfy the needs of all.

Making 1,000 zongzi a day

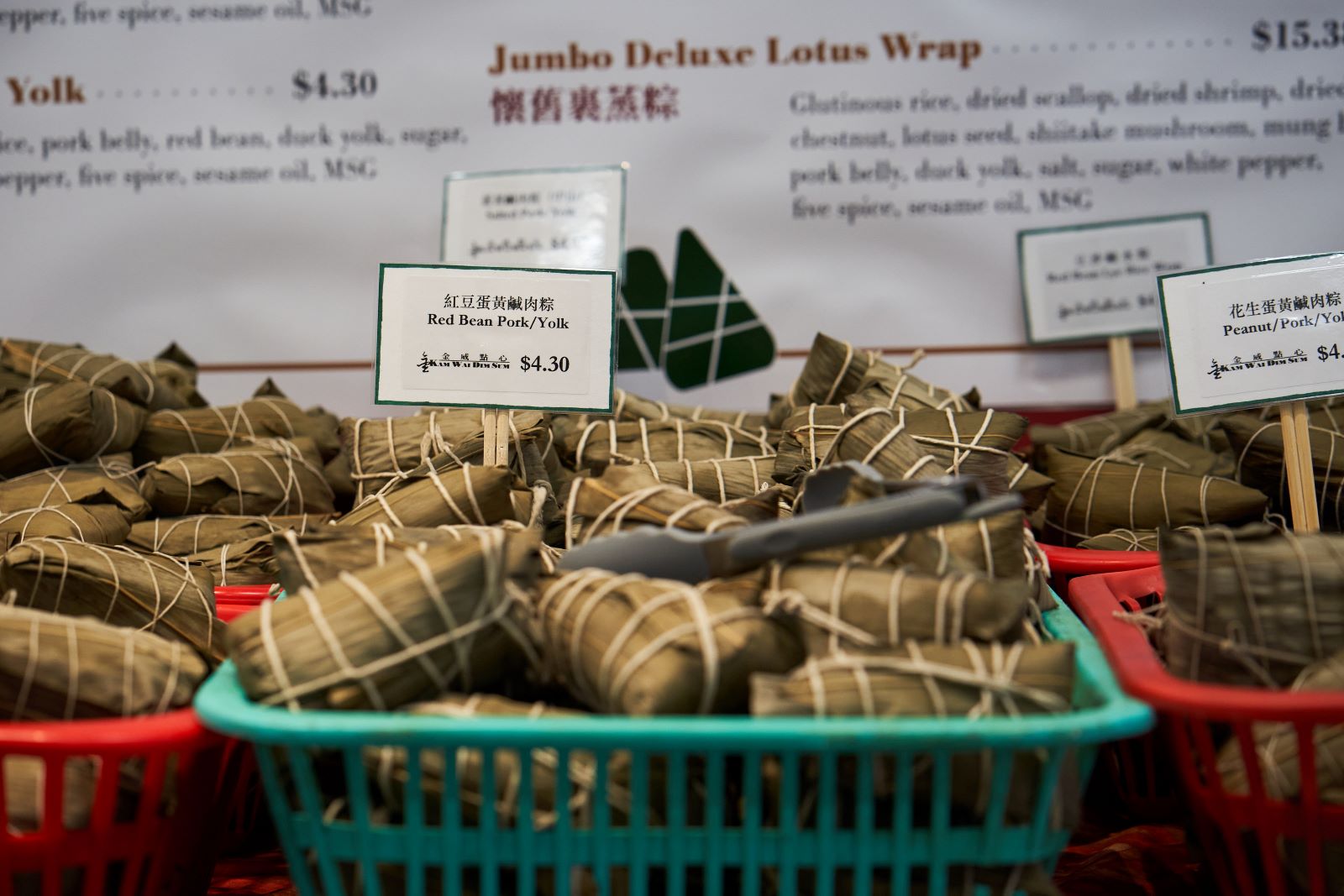

Kam Wai Dim Sum in Vancouver’s Chinatown is a busy place at this time of year. It also appeared in a 2020 Tyee series on cooking through COVID. They offer about nine varieties of zongzi this year, from the basic red bean lye, to the southern favourite salted pork and duck yolk, to the magnificent jumbo deluxe lotus wrap studded with dried chestnut, shiitake mushroom, dried scallop, shrimp and more.

Where I’m from, every family has their own recipes for their zongzi, which vary from the kinds of fillings they use to the marinating process of the glutinous rice, to the ways they wrap the zongzi that leads to different sizes and shapes.

The diverse nature of zongzi creates a chance for families to share and trade their zongzi with other families, as the significance of zongzi is being able to share it.

“The beauty of sharing and trading with other families is that you get such a variety of different kinds of fillings and flavours to share with your family,” explains William Liu, who runs Kam Wai with his mother and sister.

Kam Wai has become an integral part of the Dragon Boat Festival season in Vancouver. They are the zongzi supplier for over 15 supermarkets. To handle such large orders, they start preparing and making zongzi in November for the Dragon Boat Festival season almost half a year later. They make around 200,000 zongzi for the season, roughly 1,000 per day.

A handmade work of art

The reason they have to start zongzi production so early at Kam Wai is that zongzi can only be made by hand.

“It’s not something that machines can do,” said Liu, “It’s very difficult to customize [for machinery] because the standard of each leaf and pork is unique, so you have to feel it with your hands in order to wrap the zongzi.

“The making of zongzi is an art form that’s slowly deteriorating,” Liu added, “so we’re constantly trying to find younger people to make it so we can keep the art formalized.”

Learning how to make zongzi could be a great way for young people who celebrate this holiday to bond with their families and culture.

“People are going back to their roots, seeking more relevance with their culture and trying to find more common ground with what their own heritage is,” said Liu.

“And a lot of people see their grandparents make zongzi at home, so I really encourage people to learn from their elders, to watch them and ask questions. I think that’s such an important thing,” said Liu, “Because once the art is gone, it’s gone.” ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: