One evening in March 2015, 500 immigrants and their families gathered in the largest Chinese restaurant in Canada to remember their ancestral home. That meant a lot of Cantonese-style steamed fish and braised duck, martial arts demonstrations, and the annual performances of Cliff Richard songs by a man in a pearl suit.

Everyone at the annual banquet had roots in Hoy Ping, a Cantonese county of villages 10,000 kilometres away from the restaurant in Vancouver’s Chinatown. It was organized by Hoy Ping’s benevolent association. However, not everyone was enjoying the four-hour long celebration. A few teens hid behind iPads and textbooks, wishing their parents had left them at home.

Given most of the attendees were grandparents, Doris Chow and her sister June, both in their 30s, were among the younger crowd. They were directors of the benevolent association and had a mission: get young Chinese Canadians interested in the diminishing world of Chinatown’s older generation. They knew it was nearly impossible.

“We had the same response when we were young. We would go everywhere forced by our grandparents and parents,” said June. “It was pretty painful. I think secretly, young people have a plan that when their grandparents die, they would never have to come to these dinners again.”

If you told a younger Doris that she’d be helping out with the benevolent association one day, she would have laughed. She’s part of a generation of Chinese that grew up outside the Chinatown enclave and felt accepted and integrated in mainstream Canadian society. Public discrimination and racist laws belonged to the past. Still, despite being Canadian, many were also raised in Chinese culture by their parents and, for Doris, that upbringing made her occasionally feel like an outsider.

Yet now, on this evening, she was helping honour her family’s roots in Hoy Ping as a way to make sure she remains connected to her Chinese heritage.

The Chow family’s arrival in this country is linked to Canada’s 100th birthday – as it is for many Chinese immigrants. In 1967, the federal government took a big step towards embracing a policy of multiculturalism. A new points system for immigrants based its criteria on merit rather than country of origin. This had the effect of pushing the door open much wider to Chinese immigrants. The Chinese Exclusion Act might have been repealed two decades earlier but until the new system was introduced in 1967, immigrants from Europe had still been favoured over East Asians.

A flood of Chinese arrived in Canada after the new system was instated, many to escape communist China. The Chow sisters’ father, Chow Tin Man, was part of that wave. Family legend has it that he swam to escape the Chinese mainland in the early 1970s. The four-kilometer stretch of sea between the mainland and Hong Kong’s New Territories was a popular route for escapees, though swimmers risked sharks, patrol boats, and exhaustion.

But to start a life in Canada, Tin Man made use of a powerful network that operated out of Canton for over a hundred years: benevolent associations.

Ever since the Cantonese began emigrating in the 19th century, they had set up benevolent associations wherever they landed to keep ties with the motherland. Membership is based on family clans or counties of villages, like Hoy Ping. Associations also helped immigrants in their life overseas: lending money, providing boarding, finding jobs, and shipping bones of the deceased back home.

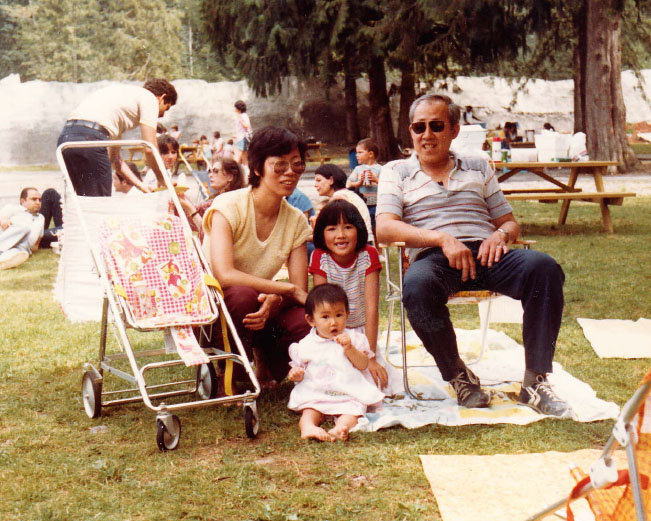

Tin Man, who was from the Cantonese county of Hoy Ping, heard that a fellow member of the Hoy Ping association needed a cook for a restaurant he had opened in Vanderhoof, B.C. As the eldest of five siblings, Tin Man took on the burden of crossing the Pacific and steering his family toward a better life. He accepted the job, and in the years that followed, he married, became a father, and brought his parents to Canada.

Tin Man later got a job with BC Ferries and settled his family in a Vancouver Special on the city’s east side. The iconic red-brick and white stucco homes offered a popular living arrangement for working-class immigrant families. Doris and June were upstairs with her brother and parents. Her father’s parents were downstairs, making it easy for them to help take care of Doris and her two siblings.

By the time Doris was born in 1982, newcomers arriving under Canada’s 1967 policy changes had transformed the local Chinese community. The Chinese population in Metro Vancouver rose to 84,000, five times the number before the points system, and was on its way to becoming what experts call a “majority-minority” in the region.

Chinese culture seemed easily accessible when Doris was growing up, a comfort to immigrants like her parents. Her family watched a Chinese television channel that played Hong Kong soap operas. Everyone their mother knew seemed to be Chinese. Doris was raised by her grandparents, who spoke Cantonese. Doris’ grandfather would often bring her to the Hoy Ping association headquarters in Chinatown so he could play mahjong with his friends. Doris would sit listening to the clattering of the tiles and chattering of old men in their village dialect as she waited for him to finish playing and take her home.

Then there was the world at school. Doris spoke English and learned about the world in English. Her classmates were a mix of ethnicities. But when it was time to go home, she was back in a Chinese world. The two worlds in Doris’ life seemed as different as black and white. She wasn’t sure which one she belonged to.

“I really wanted to be more Canadian,” said Doris. “To my parents and older Chinese generations, I wasn’t Chinese enough because I was speaking more English. Then with some of my friends in school, it was like, ‘Oh, you’re too Chinese. You’re not Canadian enough.’

“It was this weird middle ground of not being Canadian and not being Chinese and not even being a hybrid because you’re not ‘something’ enough,” she said.

A grandmother’s wish

In 1997, Doris’ father died. In 1999, their grandfather followed. Their grandmother didn’t want to be a burden on her son’s family since her son and husband weren’t around, so she insisted on moving out and relocated to a small suite in Chinatown. The apartment was in a building owned by the Chinese Freemasons with units for independent seniors. Doris and June’s visits to see their grandmother would draw them deeper into the Chinatown world.

For Doris, it became obvious that her older sister seemed very at home in the neighbourhood. June was also a Canadian-born, but she also seemed more in touch with her Chinese side, having absorbed more Cantonese from the family, even slang and old colloquialisms. June seemed at home being a hybrid of both cultures.

There’s a Chinese word in overseas communities to describe local Chinese born outside China: tusang. The literal meaning is “earth born.” Elders often believe tusang are easily assimilated into the local culture. Because of this, many who’ve met June in Chinatown are surprised she’s Canadian-born as she’s able to speak with them so easily. Some have even asked when she came to Canada. “I’ll chat up any old grandma just because I can,” said June. “For me, it’s a lot more of a community. I feel like I belong.”

During the Christmas of 2012, the grandmother of Doris and June caught a bad case of pneumonia. The sisters were in and out of St. Paul’s Hospital that holiday for visits as her condition worsened. There was one thing their grandmother made them promise: help the Hoy Ping association. It was the one place in Chinatown where she knew she could get help if she needed it. “It was then we realized how valuable and engrained it was to her,” said Doris.

By then, Vancouver’s Chinatown, nourished by a century of immigration, had come to represent a repository of older Cantonese culture in sharp contrast to nearby Richmond, an ethnoburb more reflective of modern day Mainland China or Hong Kong.

Diminishing numbers of young Chinese Canadians today have roots in Chinatown, and even for those that do, it’s extremely rare for them to get involved in the aging neighbourhood.

For those rare individuals, it’s usually family relationships that spur them to connect with their culture’s history and traditions, according to UCLA’s Andrew Fuligni. He studies how children of immigrants in North America build cultural identity.

“The acquisition and maintenance of culture doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” he said. “If teens are in a family that’s very confrontational where they don’t get along with parents, it’s less likely that they will listen to cultural messages and identify with them and they’ll more likely drift away. If they have good communication with their family, they’re more likely to consider and identify with their culture.”

Doris and June’s grandmother died at the age of 96 in 2013. Later that same year, the sisters, having earned the trust of the Hoy Ping leaders, joined the benevolent association as its youngest directors.

‘Very guarded, very exclusive’

Longtime Chinatown leaders are often reluctant to welcome new helpers and perspectives. “Chinatown is very guarded and very exclusive,” said June. “You can’t just send young people down to the community when they want to be involved.”

However, there is a consensus among aging associations that young blood is needed to help Chinatown, even if the stubbornness of some leaders is a stumbling block to progress. The neighbourhood, which has seen Chinese immigrants congregate in larger numbers in Richmond and elsewhere in the region, is facing rapid change due to the boom in Vancouver’s land prices. Longtime favourites spots in the neighbourhood, like the Lee Loy barbecue shop, have been forced to move out. Others, like Tosi’s century-old Italian grocery, are shutting down entirely. And then there are the fires and structural damage that have devastated old buildings and their tenants.

Moving into the historically working class neighbourhood are all things higher-end: condos, espresso bars, cocktail lounges, restaurants, and clothing boutiques. Some local seniors have dubbed their increasingly unfamiliar neighbourhood “Coffeetown.”

So Doris and June helped start a new group for young people interested in the neighbourhood’s future and heritage. They called it the Youth Collaborative for Chinatown. They began with public mahjong to liven up Chinatown’s streets, to bring back the bustle they remembered from their childhood in the neighbourhood. Young and old, Chinese and non-Chinese came to play.

“Instead of talking about what’s bad, we wanted to do something good, and start building what want to see,” said Doris.

The youth group also helped start Saturday Cantonese classes. It was something once dreaded by many children of Chinese immigrants, but turned out to be a hit with both Chinese and non-Chinese. The class called the neighbourhood their “textbook,” with students venturing out to practise in shops and on the street.

The renewed youth presence in the neighbourhood came at an important moment: in time for the fight over 105 Keefer, a 12-storey development many said was too big and too out of character for the neighbourhood. It would have had 106 condo units, with one floor reserved for 25 units of social housing. Politicians, planners, real estate tycoons, and Vancouverites clashed during a four-day public hearing.

While almost all who weighed in over the development claimed to love Chinatown, they had different ideas for its future. Some liked the way the economic development was going, while others wanted to see below-market housing prioritized, especially for the senior population that depends on the neighbourhood.

Many people under 40 spoke at city hall, including Doris and June, who were there every day. They helped write letters, started petitions, organized transportation to city hall for seniors, encouraged and signed them up to speak, and organized Chinese Canadian war veterans to take a public stand against the project.

The development was eventually rejected by city council.

As Chinatown’s story continues, June notes that young people can’t be forced to explore their heritage.

“It’s a much more powerful model when young people self-identify and have self-discovery to come down out of their own free will to participate or get involved,” said June.

‘A sense of transnational belonging’

Joining a benevolent association isn’t for every child of Chinese immigrants – and even if you wanted to, they might not let you in if you can’t remember your grandparent’s Chinese names or your ancestral village. Connecting with an unfamiliar culture might not be for everybody either, especially if your immigrant family left their homeland generations ago.

But diaspora theorist Ien Ang says that anyone who seeks out their roots in our increasingly multicultural world will find something special, a “powerful sense of transnational belonging” with other dispersed peoples scattered around the world.

Doris said she still lives in a “middle ground” of cultures but feels at home in both. She knows she’s part of a long history of Chinese who live overseas, a history of immigrants like her father looking for a better life.

She spends a lot of time in Chinatown — she works a stone’s throw away at Potluck Café and Catering in the Downtown Eastside — and has uncovered more personal stories since she started helping out in the neighbourhood. One day, she met the man who hired her father when he first came to Canada. He told her a story about how her father used to sleep on top of the restaurant’s fridge.

Another day Doris was walking down a Chinatown street when a senior hailed her. The senior said she recognized Doris by her appearance because she had been good friends with her grandmother. The two of them had often gone for strolls in Chinatown, the older woman fondly recalled.

Doris marvelled at the thread that tied her beloved grandmother to this woman she happened to encounter in Vancouver’s oldest enclave of Chinese culture. “I started to realize that those relationships were bonded by this culture,” she said.

At the same moment, she was struck by another insight. Being in Chinatown didn’t just make her feel more at home with being Chinese. “Funny enough, I also felt more Canadian at the same time,” she said.

PLEASE SHARE YOUR STORIES

What is your story of growing up Canadian with family roots in another land? If your parents were immigrants — Chinese and otherwise — we invite you to share your experience of forging an identity in Canada. When do you feel or don’t feel Canadian? How do you feel about your immigrant background or experience? Post a comment below, or send us your tale via email at [email protected], subject line: Identity Tale. Thanks!

To read or share the entire five-part series ending today, go here. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: