The sulfur-yellow industrial lights of Shell's Scotford oil upgrader cut through the thick April drizzle, setting the dull grey towers supporting them into high relief like a city skyline seen from a distance.

There was a faint sour smell in the air, and the low rumble of heavy machinery. The rain didn't so much pelt the surrounding prairie landscape as envelope it.

I'd driven 40 kilometres northeast of Edmonton on this miserable afternoon to get a look at the place where policymakers in Alberta and Ottawa are hoping to demonstrate the climate's salvation: the ability to suck carbon gasses out of industrial waste plumes and imprison them securely away from the atmosphere.

Together, Ottawa and Alberta have bet $865 million that Shell can turn its Scotford upgrader into a global leader in such carbon "capture and sequestration" -- known as CCS for short.

Shell's project, code-named "Quest," has yet to break ground. But that it even reached the drawing board is a rare modest triumph in a dismal couple of years for the challenging technology it relies on. This industrial outpost on the prairies processes oil sands crude from Shell's jointly-owned Muskeg River mine, near Fort McMurray. When Quest is up and running, the company expects it to capture a megaton (1 million tons) of carbon gas each year, or about 1/49 of the oil sands industry's 2010 climate footprint.

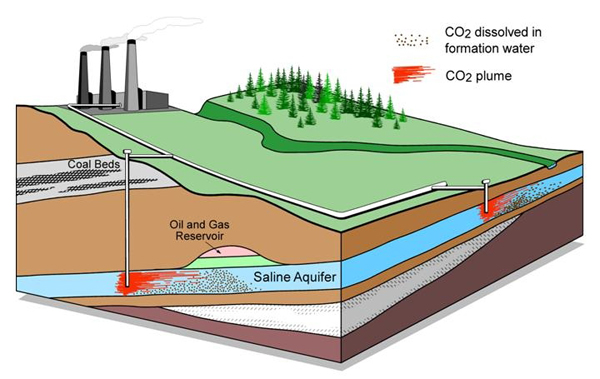

That carbon will be transported 80 kilometres north by pipeline, then injected two kilometres underground into Alberta's deepest saline aquifer formation, the Basal Cambrian Sands.

Alberta is counting on duplicating and expanding Quest's capabilities to achieve 70 per cent of its greenhouse gas reductions by 2050. Without the technology, Alberta would effectively have no climate change strategy.

That makes it a risky bet any way you look at it. Critics offer a variety of compelling reasons why it'll never pay off -- and point to a growing roll of cancelled or suspended CCS projects in Alberta, the U.K., and elsewhere.

That's one view. Other observers argue that Alberta's experiments with carbon capture and storage may be its most important future legacy, with a wider impact on Earth's climate than anything else the province is doing to cut its CO2 emissions.

Putting the oil sands' carbon back underground may have little to do with it though.

Underwater economics

Driving back to Edmonton on Highway 15 past drenched farmer's fields receding into the horizon, it was hard to believe this region was once home to a tropical seacoast.

That was 350 million years ago. But a coastal reef from that prehistoric ocean might one day help solve a very contemporary problem. Geologists have dubbed the 600 square kilometre structure, "Redwater."

Now located beneath a hard rock cap about one kilometre below prairie fields, Redwater's porous remains could store an estimated one billion tonnes of CO2, equivalent to annual emissions from 215 coal-fired power plants.

That tantalizing prospect formed the basis for a years-long partnership between the province of Alberta and Calgary's ARC Resources Ltd. The goal was to bury 20 years worth of greenhouse gas emissions from a strip of bitumen upgraders northeast of Edmonton. But the "Heartland Area Redwater Project" was suspended indefinitely last fall.

"There are no economics," ARC Resources' joint ventures manager William Sawchuk explained after the decision. "Anything a company does around [carbon capture and storage] comes at a cost."

The same story has played out repeatedly over the past couple of years: big hopes that gave way to sober economic realities and ultimately abandoned plans.

There are now only eight large-scale CCS projects operating around the planet, and the figure hasn't budged in three years. In fact, the author of a recent Worldwatch Institute report found that major carbon capture and storage initiatives -- whether operating, under construction, or on the books -- actually declined from 2010 to 2011.

"For a very small industry that's still in the developmental state, it's not a good sign," Worldwatch's Matt Lucky told National Geographic News. "This is a period when it should be exploding, so this doesn't signal significant growth of the CCS industry in the near future."

Ambiguous politics

That's a difficult assessment for Alberta's political leaders to embrace, after promising $2 billion to help build four CCS projects so far.

The building program served two important purposes when it was announced in 2008.

First, it sought to take advantage of a serendipitous fact of Alberta geology: that the home of Canada's largest reserves of coal and crude oil is also home to many of its largest saline aquifer formations, underground layers of sponge-like rock suitable for storing carbon.

Capturing carbon and sequestering it in those formations held out the enticing potential to substantially slash Alberta's greenhouse gas emissions without sacrificing its vast fossil fuel industry.

As a sort of bonus, captured CO2 could alternatively be injected into aging oilfields whose production was in decline, to drive a billion or more barrels of additional conventional crude to the surface.

The second purpose was to burnish Alberta's image. Two billion dollars invested in CCS technology was evidence for audiences the U.S. and elsewhere that for all the negative attention being heaped on oil sands production, Alberta was in fact a "clean energy" leader.

It was a message Premier Alison Redford, in office barely a month, carried to Washington last November after President Barack Obama rebuffed TransCanada's Keystone XL pipeline.

Redford told prominent members of congress to note "what Alberta is actually doing," on energy policy, drawing attention to the province's billion-dollar investments in carbon capture and storage.

A week later Redford didn't sound quite so confident about CCS technology, telling the Calgary Herald editorial board there are "better initiatives and opportunities" to cut emissions.

Big and expensive

The trouble with carbon capture and storage is, and has always been, cost.

Take Shell's Quest project. The company must connect three hydrogen manufacturing units at its Scotford upgrader to an absorber vessel that can compress and dehydrate CO2 into a dense fluid.

This can then be pumped 80 kilometres through a buried 16-inch pipeline, specially designed to transport CO2. The pipeline feeds into a vertical drill shaft reinforced with three barrier layers of steel borehole casing.

Once dispersed into a saline aquifer two kilometres beneath the surface, the CO2 must be constantly monitored to ensure that's where it stays.

The price tag for this impressive feat of engineering? $1.3 billion.

That may not sound like much relative to the oil sands sector's investment of $15 billion in 2011 alone. But Shell's Quest project will capture and bury only one megaton of CO2 a year. That's just slightly more than a week's worth of industry carbon emissions.

And it's a far cry from the 139 megatons of carbon capture Alberta's government expects from CCS technology by 2050, if it's to meet 70 per cent of its climate target.

That would require the equivalent of 139 Quests all running at the same time.

"The question is, how do you get there?" Pembina Institute policy director Simon Dyer told The Tyee Solutions Society. "So far we're just seeing very heavily subsidized pilot projects."

Awaiting the 'flat-screen' price plummet

When Alberta's Redford brags to U.S. policymakers about her province's efforts to capture and store oil sands carbon, she's referring to the $745 million it's pledged for Quest and a further $495 million being put toward a new upgrader and carbon pipeline in the province's Industrial Heartland region.

But policymakers know the technology's price needs to shrink dramatically for CCS ever to be deployed on a wider scale.

"Think about how expensive flat panel screen TVs were 20 years ago," Bob Savage, director of Alberta's climate change secretariat told Tyee Solutions. "Today you can get one for under $1,000. The situation with CCS is no different."

No doubt the experience gained in actually building and operating pilot projects will reduce the cost of capturing carbon and piping it underground.

But another way to improve the economics of CCS might be to raise the payoff, by raising the price that Alberta charges industrial producers for the carbon they release to the atmosphere rather than capture and sequester.

For most CCS projects to be economic that price, now $15 a ton, must go up to at least $50 -- and probably closer to $100 -- according to IHS-CERA, a U.S.-based energy consultancy.

Even then, it found, the ability to deploy the technology in Alberta's oil sands might be limited. "Carbon capture and storage is most feasible at the upgrader stage," said the consultancy's senior director for global oil, Jackie Forrest. "At the operating sites emissions are more dilute and more expensive to capture."

Another problem is that while much of the rest of Alberta is well endowed with underground geological formations, there are few beneath Fort McMurray, requiring construction of a new network of southbound CO2 pipelines.

Forget flat-screen TVs then. Think instead rich women in SUVs.

The CCS experience has so many layers of technical and economic complexity, says Manitoba-based international energy and climate thinker Vaclav Smil, that it should really be compared to an affluent U.S. neighbourhood, where, "we can see nearly 5,000-kg cars driven by anorexic 50-kg females to buy a 500g carton of a slimming concoction."

"Commercial, practical, reliable, affordable CCS," Smil wrote in an email to Tyee Solutions, "is not even around the third corner."

Doing It For The World

Maybe not for the oil sands operations ranged north and south of Fort McMurray. But in theory Alberta's CCS program could make a big impact on an industry of much wider concern for the planet's future climate: coal.

"In China people are building coal plants daily," said Kirk Andries, executive director of Alberta's Climate Change and Emissions Management Corporation. "If you could pioneer technology here in Alberta where you're dealing substantively with coal-fired power generation, that could be applied anywhere in the world."

In many ways Alberta is an ideal laboratory for the so-called "clean coal" experiment.

Not only does the province have more than a century's experience mining and combusting coal. But many of the province's coal-fired power stations -- the source of three-quarters of Alberta's electricity and most of its greenhouse gas -- sit squarely atop the biggest saline aquifer formations in Canada.

Add to that a provincial community of geologists, engineers and academics on the vanguard of global CCS research and, "if you can't do carbon storage in [Alberta]," says McGill University economics professor Christopher Green, "then you'll have problems with most other places in the world."

Until recently, two out of the four projects supported by Alberta's $2 billion CCS fund dealt with coal, not oil sands bitumen.

One of those is an ambitious and complex scheme developed by Swan Hills Synfuels. The company plans to drill into a coal seam 1.4 kilometres beneath the Earth's surface, pummel the coal with heat and steam, pump the gas by-product to a processing plant on the surface, where it will be stripped of a pure stream of CO2.

That CO2, more than 1.3 megatons each year, will get re-injected into aging oil fields nearby to revive production. The remaining "syngas" will generate enough electricity to supply about 300,000 homes.

"[This] has the potential to change the way we use our vast coal resources," then-Alberta energy minister Ron Liepert said last year, after his government signed a $285 million deal to support the project, the first of its kind in North America.

But if that deal was one step forward for Alberta's "clean coal" effort, the abrupt cancellation last April of another was a step backward. Supported by $778.8 million in government funding, TransAlta's $1.4 billion Pioneer Project would have buried one megaton of CO2 a year from the company's Keephills-3 coal-fired power plant outside Edmonton.

TransAlta determined that, "the technology works and capital costs were in-line," but was unable to see how Pioneer would be economic in the long-term without a higher penalty for released carbon, or clearer emission regulations for coal-fired power.

"If that's done properly," Don Wharton, TransAlta's vice-president of policy and sustainability, told The Globe and Mail, "then CCS projects, as well as other emissions-reducing projects, would be more encouraged to go ahead."

The implication was obvious: carbon capture and storage may work to slash greenhouse emissions. But it won't happen without the support of an effective climate policy.

Tomorrow: The odd disconnect between political leaders in Alberta and Ottawa on oil sands policy. Find the entire series to date here. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Politics, Labour + Industry, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: