It was a happy day when Avi Friedman's parents moved into their first home. "We had running water in the house and bathrooms," he recalls. "It was unbelievable."

The family's move into a 350-square foot home marked a life-changing step up from the tent Friedman had occupied with his parents since birth. Friedman's parents had left Europe during the Second World War for Israel, where he was born in 1952.

After completing a bachelor's degree in architecture and town planning from the Israel Institute of Technology, Friedman immigrated to Canada at age 28 in 1980 to embark on graduate studies in architecture at McGill University. Ten years later, Friedman and his wife, a University of Montreal English professor, purchased their first home in Montreal, where they still live today.

Like others his age at the time, Friedman recalls his surprise at how accessible housing prices seemed to be when he arrived in Canada.

"I was amazed I could buy a home on two years' salary," he told a packed lecture theatre at SFU Woodward's on Sept. 21. He delivered the keynote speech at a Vancouver workshop last week on how to expand affordable housing options for people with incomes between $35,000 and $80,000.

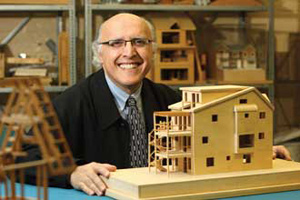

Affordable housing is an issue close to Friedman's heart. The McGill architecture professor and founder of the university's affordable homes program has dedicated his professional life to the study, construction, and critique of affordable housing in Canada. He is one of the world's most prominent housing experts.

Like many parents of children born in the '80s and '90s, Friedman has watched housing prices rise with consternation, dismayed at how his own opportunities for prosperity are no longer accessible to his two adult children.

I sat down with Friedman after his SFU housing workshops finished Sept. 23. For him, affordable housing means accessible home ownership, not just rental housing or government-subsidized housing.

"I don't want to discount renters," he tells me, "but I believe categorically in ownership. It is important in life to create a personal capital."

Vancouver's 'serious problem'

Most seniors spend their life savings in the final two years of life on health-related expenses, he notes. Life-long renting can prevent people from saving to support their own future healthcare needs and those of family members.

Still, many Vancouver residents will tell you that home ownership is beyond their reach, and local salaries aren't about to rise enough to support the cost of buying real estate here.

"If it was not obvious before, it's extremely obvious now that Vancouver has a serious problem," Friedman says.

What to do in a city where average resident incomes seem lifetimes away from local home ownership costs? Change the system at its roots, Friedman says. That means radically re-thinking the way homes are built, located, sized, and sold so that home ownership is accessible for people of diverse financial backgrounds.

He emphasizes there is no "one size fits all" solution for building affordable housing. His suggestions are intended for use in parts of a city where they fit the best. Most importantly, housing needs to be understood as an instrument of social equality and civic participation. Without the roots of a home, people can't fully participate in society.

"The common denominator for everyone needs to be that we all share the common value that people living in affordable housing benefits the public at large," he says.

Friedman shared his ideas for housing innovation with The Tyee and the people who participated in his recent local housing workshops. Here's what he suggests for expanding affordable housing in Vancouver.

Strengthen political will, counter NIMBYism

"The biggest obstacle [to housing innovation] is lack of conversation between the key stakeholders," Friedman says.

"And I'm talking about the region, not just the City of Vancouver. Municipalities need to put their hands on their hearts and say, 'Yes, we will make every possible effort to make affordable housing happen.'"

Political leaders must stand up to the NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) sentiments of their voters, Friedman adds.

"I often see leaders -- councillors, elected officials -- capitulating too quickly to NIMBY sentiment because they're afraid to lose elections."

A common NIMBY sentiment is that increased population density and income diversity creates problems in neighbourhoods, Friedman says.

"When someone disrupts your calm, it's natural to be very agitated and aggressive," he says. "The tendency is to believe if there will be more people [in a neighbourhood], somebody will eventually suffer. Which is not the case."

Vancouver's Pivot Legal Society recently launched a counter-NIMBY toolkit called "Yes In My Back Yard," which intends to educate citizens about supporting progressive projects in their own neighbourhoods.

Municipalities should adopt such toolkits and campaigns when putting forward new housing plans, Friedman says.

Build homes designed to fit individuals' incomes

One of the first projects to come out of Friedman's affordable homes program at McGill in the early 1990s was the Grow Home, a two-storey townhome designed for affordability. The basic, open-concept home is designed for its residents to "grow" the home -- build more rooms by installing partitions, for example -- as their own resources grow over time.

The unfussy construction and no-frills design kept prices accessible for single-parent families and single-income households, groups that would have otherwise been shut out of the ownership market.

Montreal's first Grow Homes sold in 1991 for $75,900. At the time, an average comparable market home cost $149,900. After 10,000 Grow Homes were built and sold, Friedman and his associates stopped counting the number they produced.

Rethink home construction

Friedman looks to the efficiency of the automobile manufacturing industry as an inspiration for the future of home construction. "Why haven't people been priced out of buying cars like they've been priced out of buying homes?" he asks.

Car manufacturing differs from home construction in two significant ways. Labour is more efficient in that much of the work is automated, and the industry is characterized by its production of customizable parts.

The same systems, Friedman says, can and should be adopted for the home building industry to bring down construction prices and, by extension, increase affordability.

Build more homes by reframing our expectations

The lure of big profits from speculators draws Vancouver developers away from the affordable housing sector, which Friedman sees as problematic.

"A major issue in the region is speculation. Many people are coming here and offering large sums of money, and the developers have less inclination or interest to work or to build for lower-income people. They want to go after the fancy condos on which they can make tons of money," he says. "There needs to be some way to explain that you can make a lot of money building affordable housing."

Friedman's Grow Homes are an example of profitable affordable housing. "You can cater to the top [end of the home-buyer's spectrum], or you can work on volume," he says.

He emphasizes the need to re-tool the expectations of both builders and buyers. Many contemporary design innovations, for example, have inflated our expectations of what a new home should look like, and those expectations drive costs up. Features ranging from the obvious frill of cavernous dream kitchens to more subtle add-ons like cutting-edge sustainability features increase costs, Friedman says.

"We've complicated homes so much. We're building them in such a complicated fashion," he says. That doesn't mean aesthetics and quality materials must be sacrificed in the name of housing. Building smaller and more efficiently using space and materials will be key for the sustainable, financially accessible future of home construction.

Affordable housing should be about tradeoffs

Looking back at his own first years as a new homeowner and new Canadian citizen, Friedman recalls his humble beginnings, which to him emphasize the necessity of compromise.

"We bought a home that was in terrible shape," he recalls. "When we moved in, it was not a dream house. It was a nice neighbourhood. It was a dream location. But we recognize in life, you cannot get everything."

The same philosophy applies to his approach to building and expanding affordable housing: it requires innovation, motivation, and above all, tradeoffs.

Devising new ways to build affordable housing, then, may require that we get honest with ourselves about what we can and can't live without. That means a close examination of how to live more simply, and with less.

"Life, work, and affordable housing are simply about tradeoffs. We cannot have it all," he says. "We're building Cadillac homes, but what about sizing down our expectations?"

One thing Friedman won't cut corners on, of course, is the task of making home ownership more widely accessible. "Providing homes to young people today," he says, "will lift the social burden in the future." ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: