[Editor's note: This is the latest in Linda Solomon's occasional series about a new life in Vancouver as a single mother with two boys and no television.]

"How much for a two-day pass?"

"Three hundred and sixty-seven dollars, and that gets you into both parks," the cashier said, flashing a made-in-Disney smile.

"I only want to go to Disneyland," I said. "How about if I buy tickets just for Disney, for two days."

"It comes out to be the same," she said.

Over her head, I read: Disneyland, population 500,000,000.

Five hundred million.

I looked from my eleven-year-old to my five-year-old and wondered what it would cost me to change plans. We could drive to Joshua Tree and enjoy the desert wilderness and the brilliant sun. Cactus, too. Just for the price of gas. Would they weep as they recounted the moment to their therapists later, the moment their mother had substituted a hike for a dream. Had taken away their cotton candy and told them to eat rocks?

I handed the clerk my credit card.

Three hundred and sixty seven dollars is a lot of money to this single mom. I had made the decision to bring my kids to Disneyland out of Christmas-seasoned guilt, the effort to compensate for the fact that they came from a broken home by giving them an outrageous kid-style pleasure that I wouldn't have considered under normal conditions. It had been only a fleeting dive into holiday darkness, but by the time I resurfaced, the tickets had been bought. They were nonrefundable, like the promises I'd made about the fun we'd have exploring the rides in the California sun.

The computer spit out a curve of numbered paper. I signed. Music filtered from loud speakers. "A Bicycle Built for Two." Heavy on the banjo. We passed through the security check, finding a long line of people leading up to the entry gates. It was 9 a.m. and the park opened at 10.

Yearning to enter

"I'm bored," one of my children told me. "I'm bored," the other one added. "Mom," the first said, accusingly.

I got out pens and paper. I drew pictures of us as we had looked in the airport the previous day in the photo booth movies we had made, our faces distorted. We laughed until we cried and then I drew more.

Despite the fact that we had an hour wait, hundreds remained on their feet, shifting uncomfortably, as if unable to defy some unspoken corporate law.

My kids kept laughing as I drew different distorted versions of the three of us. People continued standing. Every few minutes my younger son asked how much longer. Fifty minutes, 47, 42. Time stretched in "how much longer?" increments. Ten minutes before 10 the gates to Disneyland opened and like eager sheep we trotted towards the feed. Around us, the world had turned TV-Technicolor. And yet, we had not yet truly arrived.

We attempted to walk on the sidewalk but a jowly, gray-haired Disneylander in uniform snarled, "Do you have passes?"

"No."

"Then you can't walk on the sidewalk."

"Where should we walk?" I asked.

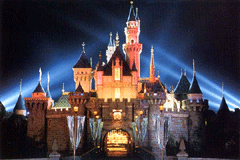

"You should walk in the street and wait until the park opens," he said in a slowly enunciated singsong. Disneyland may have looked unreal, but it had a class system just like the rest of the world and people who had gotten deals through hotels and travel agents were directed to the sidewalks, while the rest of us peasants gathered in front of the barrier, peering up ahead at Sleeping Beauty's castle.

The time was now 9:55 a.m. A trumpet sounded, then a velvety voice said, "Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls: Welcome to the year of a million dreams . . . from all of us at the Happiest Place on Earth, we hope your day will be an enjoyable one."

The barrier rope dropped. We were in.

Going goofy

"C'mon," I said, as we joined the crowd running towards the Matterhorn, where in no time we were seated in a car and rushing around the mountain screaming our heads off. Ghouls leapt out from the darkness and howled at us and my five-year-old buried his face in my side and hung on for dear life, as the car plunged through the darkness carrying us seemingly to our death, righting itself just in time to zip back into the light.

We continued through Tomorrowland and headed to Autopia, a fleet of electric cars protected from disaster by the rail they ride on. A sign said, "It is possible that fuel cells may power our cars in the future." I looked around. A couple of chic Japanese teenagers wore velvet Mouse ears with red and white polka dot bows. A corpulent woman in a gray hoodie and sunglasses sported a faded Winnie the Pooh t-shirt. A father wore a foot high green rubber "Goofy" hat with drooping dog ears, while his young son went hatless. Two little girls wore Cinderella dresses and carried wands with stars at the end.

I marvelled at the couples that appeared to have come to the park without children. How could they have brought this on themselves, I wondered? Even later on the Storybook ride, which was targeted for children my younger son's age, non-child toting adults got into the colourful cars with big smiles plastered on their faces, as if nothing in the world could be more interesting than riding through a cartoon village that re-enacted Pinocchio's journey from puppet to mule and ultimately, into a boy.

Next, we did It's A Small World. Transformed for the holidays and not yet returned to its normal incarnation, the exhibit was a Christmas spectacle. Preparing myself to be completely annoyed by the fact that well into January, they hadn't bothered to take down their Christmas trees, I found myself falling irresistibly under the charm of the sweet carolling voices and the elaborate dancing figures representing different countries.

As the boat glided into the castle, passing dazzling lights and ornate figurines, I found myself, thinking, "This is pretty good." For a second I even forgot that it had all been constructed to power an industry. I put my arms around my children and my heart wanted to burst with joy as we were pulled along from one endearing sight to the next. Somewhere between France and Japan, I started crying. My 11-year-old shot me a warning look. "Mom," he said, pleadingly. The boat pulled back out into the light and he checked to be sure no one was watching me dab my eyes.

Confronting our demons

"C'mon," I said, grabbing my five-year-old's hand. "I know something really fun we can do. You love Star Wars." There was only a small line outside the Star Wars tour and we quickly got in. There of course was the inevitable DV (Darth Vader), who seemed to have replaced Mickey Mouse as the most frequently seen fantasy figure at the park. The presence of this dark, military figure in the heart of popular culture seemed to reflect the fact that America had left innocence far, far behind . . . .

As we reached our destination, a room with five space age doors, my five-year-old made his decision. "I don't want to," he said.

"It'll be great," I said.

"No," he said.

"Yes!" I said.

It hadn't been that long ago that I'd had to take him out of theatres during the previews because they frightened him. Why was I now pushing him the other direction, straight into his fears?

Oh, yeah. Four hundred dollars.

Anyway, I told him, there was no way out. We were part of a throng of humans boarding the starship. When it "took off" the room tilted to one side, righted itself, jerked up, then down, then rocked violently from side to side. It lurched forward. Then a 3D simulated flight film made us feel like we were traveling at the speed of light while being piloted by a monkey, faking out our reptilian brains into believing we were dropping through a black hole, careering insanely, almost crashing into a weird space city, nearly getting sucked up into a Death Star, then throwing us out into the stars like a ball volleyed out into infinity by a drunken giant. I don't remember the rest.

I was too horrified. And delighted. The mixture of sickening fear and total excitement had me screaming at the top of my lungs. I wanted it to be over more than anything. I wanted it to go on.

I was vaguely aware of the little person to my left white-knuckling it as the room bucked like a rabid rodeo horse. We spun through another black hole, righted ourselves and prepared to die. Then it was over.

"Great," I thought as we unsteadily walked out of the spaceship.

"That wasn't real," my older son informed my younger son. "We didn't really go anywhere."

"I know," my younger son said.

"Are you okay?" I asked.

He nodded vigorously. "I want to do it again."

Everyone around us looked sick. We looked sick. "I want to do it again, too," I said.

Fast lane home

Wherever we went wandering Disneyland, it felt like being in a cartoon come alive and, at some point, they all got scary. Roger Rabbit's Toon Town Spin had darkness and horrors. Even the Winnie the Pooh ended with our little honeycomb train passing through a Heffalump area where, in a re-enactment of Pooh's nightmare, psychedelic figures rotated around the car, making me feel like I was on a very bad acid trip.

We ended the day at the Lego Store in "downtown Disney," where a two story Lego giraffe towered over hundreds of neatly stacked Lego boxes and my sons went into a state of prolonged consumer confusion, trying to make a choice in the face of an overwhelming number of good options.

The next morning, as I drove our Enterprise rental car from one freeway to another, making tracks back to LAX, my younger son was nursing a fever and headache while my older son stared out the window at the bumper-to-bumper traffic. He marvelled at the number of lone drivers seated in the parking lot of the freeway, while we, in the carpool lane, sped past them.

I had just finished reading Stupid to the Last Drop, a book by investigative reporter William Marsden that spells out how America's need for oil will destroy Canada. Marsden's book had left me with the feeling that the world was coming apart. The landscape of trucks and cars idling as far as the eye could see drove the point home.

We dropped off the car and boarded a theme park ride of a different sort, the rental car shuttle to the airport terminal. A heavy-set man, travelling with his daughter and wife, eased himself into the seat across from me and the kids. The man asked my older son where we were from.

"Vancouver."

"Must be cold up there."

My son smiled and nodded.

"We're from Buffalo. We had four feet of snow and then the weather turned. It was 60 degrees yesterday."

"Global warming's going to turn the whole world into L.A.," I said, only half joking.

"Don't believe that propaganda," the man said, growing excited. He took off his glasses and wiped his hand across his forehead, then put the glasses back on.

I tried to imagine what he had once looked like, back when he was in his 20s, as he focused again on my son, told him how weather goes in cycles and how current patterns have nothing to do with the habits of human.

I imagined him svelte and handsome, hopeful and light, as he explained that the dinosaurs had all gone extinct and it had nothing whatsoever to do with human beings. "We weren't even around then," he lectured, hardly stopping to take a breath.

"It's like the ants in the anthill thinking they're in charge because they annoy humans a little," he continued, leaning forward. My son nodded, dutifully, as he would to a teacher. My son went on smiling. Beneath the smile, I recognized the look of a prisoner who was trapped and pinned down, tortured by the big man's rant. I wanted to intervene, but I have always been susceptible to listening with a smile when I want to run away from them.

I was raised in the American South, and the tendency to smile and placate out of a misplaced sense of social grace had been hard to shake despite years of feminist tendencies and allegiances. My son was merely behaving as he'd been taught to behave. What I'd give to cut that demon out of my psyche forever, I thought, still smiling along with my son and nodding my head, as if we were listening to a Nobel Laureate. Was it too late to teach my son how to extricate yourself while remaining considerate of another person's feelings? I made a note to self: try.

"Alaska Air," the driver called back.

"Yes, Siree," the man said, undaunted by the fact that we'd reached our destination and were getting up out of our seats. "Don't you ever believe that propaganda about global warming."

Fantasyland

We worked our way through the airport maze towards our gate. At the X-ray security check, I began the awkward dance of managing my computer bag, my purse, and my sick and whimpering 5-year-old, while, at the same time, unzipping my boots and trying to help both kids get their shoes off and in the bins along with their jackets. Without holding others up.

Struggling with my boot zipper, I silently cursed Richard Smith, the Brit who had tried to set off a shoe bomb, failing at exploding the airplane, but succeeding at forcing millions of travelers to take off their shoes at security checkpoints forever more.

As I wobbled on one shoe and put the other in the plastic box on the conveyer belt, I could only think he'd succeeded at destabilizing me, for one.

All this obsession with personal safety while the planet's atmosphere veers out of whack. The war in Iraq grinding on and on while Disney's cartoon fantasy world thrives. It made me think about how America had changed since July 17, 1955 when Walt Disney opened the doors to his theme park.

As he consecrated Disneyland, that father of all American fantasy had made a nod to reality. He had dedicated his wonderland "to the ideals, the dreams, and the hard facts that have created America . . . with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world."

I could only speculate about which "hard facts" he was referring to at the time. The Cold War? McCarthyism? Or had he meant earlier "hard facts," like the genocide of Native Americans. Maybe he had meant slavery. Whatever. I appreciated the nod to reality by the greatest wizard of unreality to live in the last century.

On the other side of security, we got our shoes back on. We found our gate and sat down over hot dogs and fries. As we ate, I looked around at our fellow travelers, all consuming hot dogs and hamburgers, too, and then up at the TV at the segment on the Iraqi war. The American dream hadn't changed since Disney's dedication, I was thinking. But the fact of hard facts hadn't changed either. They just may have gotten harder.

Related Tyee stories:

- Raising a Brand-Free Kid

From day one, you've got to fight Winnie the Pooh. - A World of Danger, and No TV to Dull the Roar

Life is scary. Tell the kids? - How Did 9/11 Change US Culture?

At the time, I saw Americans' 'sense of immunity' assaulted, and predicted a mental shift. Where did it lead?

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: