Anyone who’s watched a lot of documentaries lately may be ready to throw in the towel on the human race. One after another they tumble forth, an unspooling ticker tape of doom and disaster. Films about opioid addiction, voter suppression, racism, poverty and the rumbling drumbeats of extinction-level climate change.

But behind all of these big-ticket problems lurks something even more troubling. Call it the death of human feeling.

One recent offering I wish I could scrub out of my mind is American Murder: The Family Next Door. The facts of the Watts family murders are well-known to true crime followers. A man kills his pregnant wife and two young children, lies about it, is caught and convicted of the crime.

The documentary, now on Netflix, concerns itself with the smaller, more intimate details leading up the crime as well as the subsequent investigation and trial. Through text messages, emails, YouTube videos and Instagram stories, the film builds a patient and exacting portrait of what Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil. There it is in all its mundane, middle-American plainness: a crime of horrific proportions taking place in a suburban neighbourhood of bland condominiums and Ford F-150 trucks.

True crime films are plentiful, but there is something about this one that lingers. It’s the stuff I can’t wrap my head around — the ordinary nestled right next door to the unspeakable.

A similar feeling popped up in another recent film. Alexander Nanau’s film Collective premiered last year and was just announced as the Romanian entry for the 2021 Oscars. It shares with American Murder the same profound absence of human empathy. The thing that makes humans, human.

It’s one thing to witness individual evil. It’s another to see it institutionalized in a systemic fashion, by the people charged with the safety and well-being of the most vulnerable in society.

The story begins in the aftermath of the 2015 Colectiv nightclub fire in Bucharest. The club had been operating without adequate fire exits, and when a blaze broke out 27 people were killed on site and another 146 injured. But it was the death of a further 38 young people in hospital, largely due to preventable bacterial infections, that drew the attention of the news media, including an intrepid team of journalists from Sports Gazette.

This unlikely group, led by editor-in-chief Cătălin Tolontan, set about uncovering one of the most startling tales of government corruption, mafia capitalism and medical malfeasance in modern memory. The facts of the story often beggar belief. As one of the journalists working on the story states, “The story is so mind-blowing. I am afraid we’ll look crazy.”

The gist of what they uncovered was inadequate facilities, watered-down disinfectants and managers who embezzled hospital funds to buy luxury cars and eurotrash mansions. But it was the failure of even the most basic and fundamental aspects of care that proved the most shocking. When leaked video of a burn patient infested by maggots was released, people rioted in the streets demanding action. Doctors, nurses, administrators, medical manufacturers and government ministers were all implicated.

When asked how such suffering was allowed to occur, Dr. Camelia Roiu, a whistleblower who spoke out about the scope the problem, simply stated: “We’re no longer human.”

So, what lessons does this story have for the rest of the world?

Variety’s review of the film put it best: “The corrosive corruption revealed has ramifications far greater than just in Romania, for it’s indicative of a worldwide phenomenon in which people feel so disconnected from others that empathy has been replaced by avarice, and strangers are viewed as abstractions.”

Collective will be released on video on demand in November. It’s impossible to watch the film and not see shades of the same story happening elsewhere. The mobster mentality that overtook the Romanian government and the medical establishment bears an eerie resemblance to things currently taking place in the U.S.

Take the recent film by Alex Gibney, Ophelia Harutyunyan and Suzanne Hillinger, Totally Under Control, which laid out the systematic failure of the current U.S. government to forestall the pandemic.

Some of the most damning sections of the film concern the private sector’s inability to address the scope of the problem, but it also implicates government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control. The prospect of profiteering from COVID-19 drugs like Regeneron or a future vaccine is also raised.

The question at the centre of the film is why the government failed so utterly, and the answer was simple. Co-director Gibney summed it up in a recent interview with NPR: “It really is a staggering question. And I think the answer, unfortunately, is pretty dark. Trump wanted to slow-walk the testing because if you test, you find out that people have the disease. And that looks bad, and then maybe that hurts the economy. Maybe that hurts your re-election chances.”

It’s not just documentaries revealing the rot.

The convergence of money, elections and health care was also on display at the Senate judiciary committee’s questioning of U.S. Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett. The fast-tracking of Barrett’s seat is viewed as potentially a means for the Republican party to contest the U.S. election results, but there are even more profound ramifications, including the potential loss of the Affordable Care Act, a reality that would deprive millions of Americans access to adequate health care.

Historian Heather Cox Richardson, in her usual excellent fashion, offered another summation of the end game of the Republican party. “Their desire to roll back the changes of the modern era serves traditional concepts of society and evangelical religion, of course, but it also serves a radical capitalism. If the government is as limited as they say, it cannot protect the rights of minorities or women. But it also cannot regulate business. It cannot provide a social safety net, or promote infrastructure, things that cost tax dollars and, in the case of infrastructure, take lucrative opportunities from private businesses. In short, under the theory of originalism, the government cannot do anything to rein in corporations or the very wealthy.”

Truth is the most necessary and basic disinfectant, but it’s often in short supply. Watching the Senate judiciary committee proceedings, like sitting through a documentary like Collective, is to experience the impossibility of comprehending the failing of basic human conscience.

Even worse is the gross stuff of profit, the money to be made from human suffering that fuels the political decision-making process. As Romania’s interim health minister said when the full scope of the scandal was revealed: “The way a state functions can crush people sometimes.... It’s profoundly corrupt. They don’t give a fuck about anything out there.”

Arguably, the current U.S. administration’s dedication to a policy of disinformation has greatly aided and abetted the pandemic, but the inability to contend openly with reality indicates a deeper and more existential crisis besetting humanity. Does money trump compassion? And if so, what is the antidote?

Collective doesn’t offer any immediate answers. When the story broke, the Social Democratic government was toppled and the country’s president forced to resign, but even the revelations weren’t enough to stave off power and profit for long. When the Romanian general election happened, the Social Democratic Party swept back into control through a campaign of mendacious nationalism. Then it was back to business as usual.

But there are some more hopeful signs that can be taken away from the Collective story and other more recent examples of truth telling. Even in the darkest moments, people persist. Whether it’s the Romanian sports journalists, American Civil Liberties Union lawyers, U.S. senators or filmmakers.

If documentary can send you down the dark rabbit hole of despair, it can also lift you out again.

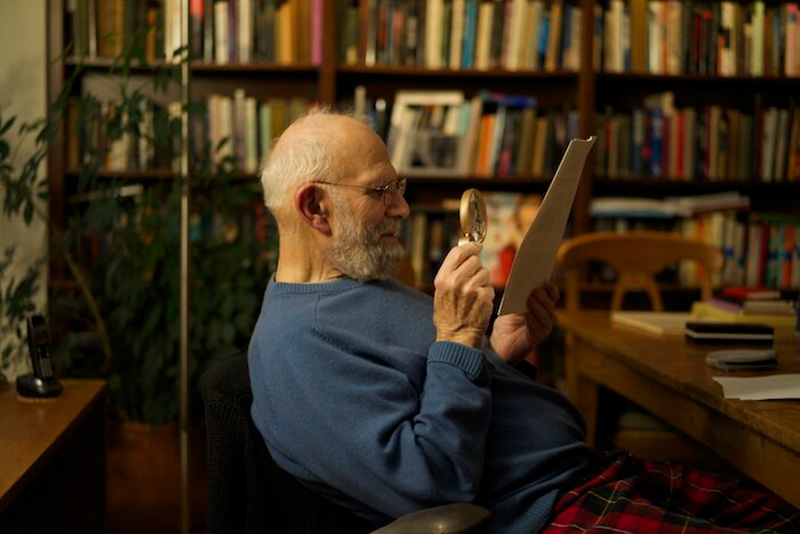

If you need to reassure yourself that there is still much good in the world, I give you one Oliver Sacks. Oliver Sacks: His Own Life is available to screen through Vancity Theatre’s online programming this week.

As a documentary it’s a fairly straightforward affair, detailing the events that shaped Sacks as a child, a young man, a physician, a writer and finally as a cultural icon.

One of the things that is most remarkable about Sacks’s style of medicine was his profoundly empathetic approach, a hands-on methodology that meant understanding people from the inside out. Whether that was hanging out with Tourette syndrome patients or talking to autism spokesperson Temple Grandin, he wanted to figure out how to get inside another person’s head, whether that person was suffering from dementia or autism.

Director Ric Burns didn’t begin shooting his film until after Sacks had received a diagnosis of terminal cancer and was given six months to live. As his friends and colleagues assert, it was at this point that he began offering a master class in how to have a good death. One of his final essays, published in the New York Times, is a masterful celebration of everything that life and death have to offer.

Of course, not everyone can be an Oliver Sacks, but as the film takes pain to note, a single person can still shift the world. One interviewee noted that many medical students cite Sacks’s work as their main reason for entering the field of neurology.

The takeaway of Sacks’s life, as well as the film about him, is that to truly help someone you must feel what they feel, understand what they understand. And even more importantly, that all humans, no matter their state, are unique, irreplaceable and of value. Deserving of care and compassion.

While one film may not erase all the ongoing travails of the world, Oliver Sacks: His Own Life is a gentle and loving reminder that empathy is really all we’ve got. Hopefully it is enough. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media, Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: