Why do we vote for jerks? On the eve of the Canadian election, it’s an honest question.

Documentary cinema offers some answers but also poses more troubling questions. There’s a bounty of films about the electoral process out these days, ranging from the upbeat (Knock Down the House) to the decidedly grim The Edge of Democracy. Amongst all of these different films, some curious trends emerge.

One the most unsettling pops up in a film called The Great Hack, now streaming on Netflix, which makes the argument that free and independent elections may be a thing of the past. In backing up this bold assertion, the film uses the story of Cambridge Analytica as an object lesson in what happens when the jerks make the rules in technology, media, finance and politics. And it reveals an even darker reality, namely the end of democracy itself.

The electoral process is where it often begins.

In 2016, the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica illegally scraped data from 87 million Facebook users and used this information to influence the outcome of the U.S. election. Micro-targeting of undecided voters, termed “persuadables,” took the form of Facebook ads designed to play on people’s deepest fears and prejudices. The jerkier aspects of human beings were inflamed, and arguably the company helped swing the election in favour of Donald Trump.

How this information was gleaned and weaponized forms the bones of the film The Great Hack, and it’s a whopper of a tale.

As Parsons Design School professor David Carroll explains in the film, “In order to send personalized messages, you need people’s data.” The more than 5,000 data points that almost every online user gives off are illustrated in the film like shedding skin cells, flaking off people in their daily transactions from their purchases to Facebook likes. As Carroll says of the promise of this digital world, “We were so in love with the gift of this free connectivity that no one bothered to read the terms and conditions.”

Directors Karim Amer and Jehane Noujaim lay out all of the major players in the Cambridge Analytica drama — journalists, whistleblowers, academics and lawyers, alongside their opponents including corporate honchos (Alexander Nix), right-wing billionaires (Robert Mercer) and Machiavellian political consultants (Steve Bannon). Caught in the middle were ordinary folk happily filling out quizzes on Facebook.

The story continues to unfold with whistleblower Christopher Wylie’s book MINDF*CK: Cambridge Analytica and the Plot to Break America, newly out this week. Whether you believe Wylie was an honest whistleblower or a wilier participant depends on where you enter the story — at the beginning when it was all fun and frolic, or later on when things began to sour.

In an excerpt from the book in New York Magazine, Wiley describes the genesis of Cambridge Analytica as a social-engineering experiment put forth by billionaire Robert Mercer as a way to “fix society.”

But along with this lofty idea was more prosaic stuff, like money and power. As Wylie explains, investing in a private company like Cambridge Analytica enabled Mercer to circumvent U.S. campaign-finance restrictions. In other words, he could spend as much money as he liked to sway elections without having to report it as a political donation, and “his giant footprints would remain hidden.” The same strategy worked in the Brexit campaign, with money being funnelled into purchasing Facebook ads that weren’t recognized as electoral spending, which is also limited by law in the U.K. The campaign even had a B.C. link, as Victoria’s AggregateIQ role played a key role in the Leave campaign’s voter targeting.

The Great Hack plays like a thriller in tracking down who knew what and when about the scandal. In the centre was a rather unlikely young woman named Brittany Kaiser, a sombrero-hatted, cowboy-booted millennial who went from volunteering with the Obama campaign to aiding the Trump camp. When Kaiser was hired by Nix, the CEO of a British company called SCL Group (which evolved into Cambridge Analytica), the stage was set to unravel democracy, beginning with people’s right and inclination to vote.

Thanks in part to the towering work of Guardian journalist Carole Cadwalladr, who encouraged Wylie to come forward as a whistleblower, the scandal eventually exploded. But as Cadwalladr says in the film, “It’s really important to understand that the Cambridge Analytica story actually points to this much bigger more worrying story. Which is that our personal data is out there and being used to against us in ways that we don’t understand.”

Cadwalladr recently took her fight for tech accountability to “the Gods of Silicon Valley: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey,” at the 2019 Ted Talk in Vancouver.

In her speech, she described the results of this social experiment in no uncertain terms: “Our democracy is broken, our laws don’t work anymore… This is not democracy, spreading lies in darkness paid for with illegal cash, from God knows where, it’s subversion and you are accessories to it… You set out to connect people and you are refusing to acknowledge that this same technology is now driving us apart.”

She reserved her most damning statement to the end of her talk.

“What you don’t seem to understand is that this is bigger than you, and it’s bigger than any of us, and it is not about left or right, or leave or remain, or Trump or not. It’s about whether it’s actually possible to have a free and fair election ever again, because as it stands, I don’t think it is. And, so my question to you is, is this what you want? Is this how you want history to remember you, as the handmaidens to authoritarianism that is on the rise all across the world?”

What Cadwalladr was calling out was taking place around the world, nowhere more dramatically than in Brazil, where the country had essentially torn itself in two, helped along by vicious misinformation campaigns that divided the nation.

The undoing of Brazil’s democratic institutions is the subject of Petra Costa’s documentary The Edge of Democracy. It exhaustively documents the rise and subsequent fall of Workers’ Party leaders Lula da Silva and successor Dilma Rousseff, as well as the rise of the far-right President Jair Bolsonaro.

As the film shows, the dream of Brazilian democracy turned to smoke almost overnight. Using the example of her own family (her radical parents as well as her more conservative relatives), Costa charts the emergence of democratic government in Brazil after decades of military dictatorship. But when former president “Lula” anointed Rousseff as the first female president in Brazilian history, Costa portrays the revenge of the far right as beginning with an anti-corruption campaign entitled Operation Carwash. It succeeded wildly, with impeachment for Rousseff and prison time for Lula. In Costa’s view, when the wealthy and powerful grew tired of democracy’s rule of law, they simply did away with it. “Democracy is only working when the rich feel threatened,” she says.

In the film’s agonizing coda, the director asks a series of increasingly difficult questions: “How do we feel with the pain of being thrown into a future that looks as bleak as our darkest past? What do we do when the mask of civility falls and what emerges is an ever-more haunting image of ourselves? Where do we gather the strength to walk through the ruins and start anew?”

She has no answers.

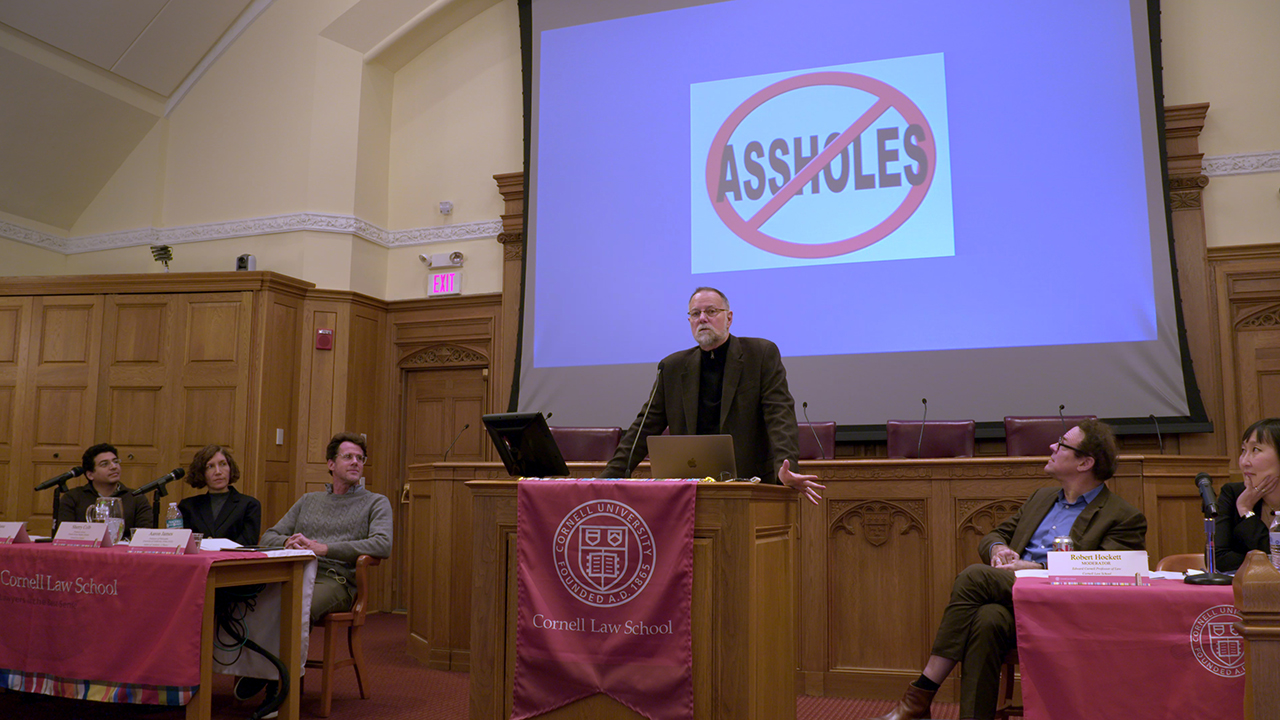

When dictators run roughshod like maniac Clydesdales over large swathes of the planet, it’s the people standing by, simply letting them, that are the most troubling. The question of personal responsibility is at the heart of John Walker’s 2019 film, Assholes: A Theory.

Walker attempts to understand the phenomenon of how assholes rise to power, but he also looks for some solutions to problem, right here in Canada. Until recently, it was assumed that Canadians made terrible assholes. Our reputation as a nice, polite, largely apologetic people seemed secure. But all of this changed when Rob Ford, a big, loud, crack-smoking thug was elected to run Canada’s largest city.

In explaining how leaders like Ford, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Jair Bolsonaro came to be, Walker’s film spends a fair amount of time looking at the example of Silvio Berlusconi, the former Italian prime minister who essentially laid the groundwork for the asshole card currently being played by politicians around the world.

As Walker’s film illustrates, if you elect an asshole to run your country, they will frame everything around their own needs and do almost anything to support the continuation of their power. Rule of law goes flying out the window.

Berlusconi created a Fellini-dream of power, sex and money that enriched not just himself, but his supporters as well. As the editor of the Economist magazine, who took direct aim at Berlusconi, remarks, this level of corruption was only enabled because the so-called good people were silent, or worse amused. Lulled by media images of sexy ladies on television, and arguably amused by Berlusconi’s shamelessness, the Italian public largely shrugged its shoulders and said, Cosi fan tutte; everyone’s doing it.

But it was the rise of the tech asshole — Zuckerberg, Dorsey et. al — that posed new problems by amplifying bad behaviour to an unprecedented scale and giving it all kinds of new platforms. Cue the rise of the trolls, the bots and the unravelling of the democratic process.

Here’s where we circle back around to some of the issues raised in The Great Hack. As Cadwalladr explained in her Ted Talk, we are all implicated in our passivity and our complicity.

We wanted the connectivity, the pleasure of social media, without the responsibility of understanding its more troubling aspects. This idea extends to the political process as well. You can’t have democracy and all the benefits it entails — freedom of speech, freedom from persecution — without understanding how it works, actively participating, and fighting for its survival.

The effort to safeguard democracy isn’t just directed at the architects of social media but to ordinary people as well. Cadwalladr ends her Ted Talk with this question: “Is this what we want? To let them to get away with it, and to sit back and play on our phones as this darkness falls?”

On the eve of the Canadian election, when we’re looking at our own decisions and thinking hard about where we go from here, it’s a damn good question. ![]()

Read more: Election 2019, Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: