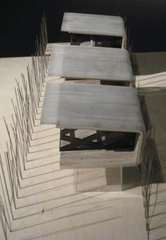

Oliver Lang adjusts a tray of tiny, carefully crafted house models as though it were a plate of hors d'oeuvres at a Kerrisdale cocktail party. Metaphorically speaking, perhaps it is. The PAC House model that Lang is preparing to unveil tonight at the Vancouver Museum could spark fresh thinking about the way we live.

Opening tonight and running through June 22, Movers and Shapers is a can't-lose outing. For design novices, this is a great introductory sampler of 20 of the most creative design outlets on the West Coast. For design know-it-alls, the world premiere of Lang's PAC House alone will be worth the trip.

But its underlying values turn the whole laneway-house concept on its ear, almost literally. Based on a typical 33' by 120' Westside Vancouver lot, the PAC concept shifts the entire single-family-residence concept sideways from a frontyard-house-backyard deal to a linear "sideyard" orientation. That is, the generously windowed "fronts" of both the main house and its smaller laneway companion face the adjacent lot, set back by 12 feet from the property next door. "It's a critique of the current Vancouver model, where all the houses are front- and backyard-oriented," says Lang. "All of a sudden, a huge potential in single-family housing is unlocked."

Much of this potential lies in harnessing the roughly 700 square feet of useless front lawn. The PAC House opens up to a shallow (12-feet-deep) but wide side yard instead. Perhaps the most salutary aspect of the PAC Home is not one specifically intended by Lang: it's the egalitarianism fostered by its configuration. The PAC's laneway house is on an architectural par with the main house. Positioned along the same axis and sharing the same view as the principal house (for instance, a green hedge along the lot line), the PAC system's laneway house does not suggest the second-rate status. Down with the condescending terms "in-law suite" and "mortgage helper" and all the secondary status implicit in the terms. I love how the laneway house is designed and sited with the same care and on the same axis as the principal house: it's just smaller.

Driving force for design

The curator and driving force behind the Movers and Shapers exhibition is Steven Cox, himself trained as an architect. Along with spouse Jane Cox and other associates, he's a brand designer. Which prompts one to hope: surely he'll have a few drinks with the architects tonight, maybe ending in a brainstorm on prying open the minds of planners and Westside homeowners.

One PAC house has already been built in a quasi-prototype project as a second storey over a conventional house in Point Grey. Earlier this week, Cindy Wilson (Lang's life and work partner at Lang Wilson Practice in Architecture Culture) offered me a brief tour. Verdict: it's gorgeous -- light and livable; its upturned roof and generous windows evoke the feeling of a much larger square footage. (To be sure, though, the floor-to-ceiling windows on this prototype aren't going to be for everyone.)

Would there be other issues to address? For sure. Sun and shade considerations for the sideyard, and fire prevention, as starters. (The ground floor is set back from the adjacent lot, but the second floor runs right up to the lot line.) But can we at least start talking about it? With a zero-lot-line in the picture, this is one scheme that can only take flight, I'd say, on a neighbourhood-wide scale.

There will also be carping about privacy, since the side yard would be so much shallower than the conventional front yard. But here is the cruel truth: there is no privacy in Vancouver -- especially on the Westside. Don't believe it? Try this: walk down a bucolic street in Dunbar or Kerrisdale -- ground zero for NIMBYism. Almost every front window you see will be solidly curtained day and night, as though the city were infested with snipers or in the throes of a heat wave. In those few houses whose owners are bold enough to draw back their drapes, a passer-by can easily see over the 20 feet of front lawn, well enough to assess their taste in furniture and whether their offspring suffer cello or piano lessons. So what's the point of a big front lawn? Mostly as a kind of feudal crest, marking the ability to own extravagantly useless land in the nation's most expensive city.

Evolving a city's housing

The PAC House also shares the architectural value of another noteworthy architect showcased in Movers and Shapers. D'Arcy Jones is presenting models for two eye-catching houses, in Salt Spring and Osoyoos -- both principle residences, both knockouts -- and both under 2,000 square feet. (Relatively modest budgets, too: about $350,000 each to construct.) Jones often persuades his clients to scale back the physical size of the house, even when the budget allows for the more commonly bulimic architecture. If the architectural ethos at Movers and Shapers is a harbinger for Vancouver, then we can feel pretty good about our civic future.

Lang is wary of seeking radical wholesale rezoning, though, which would almost certain provoke a Westside NIMBY backlash. "It's important that we think of this in an evolutionary way, not in a revolutionary way," says Lang. If the side yard paradigm were green-lighted with haste, he cautions, then quick-and-dirty developers could step in and make a mess of it all. And, there is a daunting undertow of irritable NIMBY voters -- specifically, the powerful bloc of voters who tend to live in and own single-family residences on 33' by 120' lots. The fight is already on.

Lang himself has braved a fight or two in his day, having just left the University of British Columbia architecture school faculty after an extended period of what onlookers describe as mutual friction. "A solution for a happy co-existence could not be found," he tells The Tyee, with a tight smile. UBC's loss is Vancouver's gain: aside from PAC and other projects, Lang is working with venerable urban planner Ray Spaxman on a study of housing alternatives to avoid displacement on the Downtown Eastside. Watch for that report after the study wraps up in a month or so.

Good stuff, strutted

The Movers and Shapers exhibition also brings together the top dogs in fashion, graphic, industrial, jewellery and marketing design. In cliquey Vancouver, the isolation of architecture from other more consumer-friendly design disciplines hasn't helped its cause. It's terrific, then, that the architectural highlights are embedded in a show that will attract far more than the usual archi-crowd. Design works are brought together in groups of four, one on each leg of a cruciform-shaped platform (or paired up on el-shaped platforms in the corners).

The curatorial approach makes for an intriguing series of diptychs -- Lang's sleek architectural models, for instance, next to Heather Marten's romantic streamers of Battenberg lace. Or Marc Bricault's steel-and-brass birdfeeders, next to a delicately sculpted chandelier by Omer Arbel (whom Tyee readers may know as the designer of the insanely priced condo, More than a dozen other top design teams are strutting their stuff here: just come see. With impeccable timing, Movers and Shapers argues a good case for the Vancouver Museum to get its own decent-size downtown standalone building.

Related Tyee stories:

- The Little House That Could

Could densify cities affordably, that is. The rise of the laneway cottage. - Can 'Eco-Density' Be Beautiful?

New initiative means new architecture. But how will it look? - Let's Pave Streets Green

Would you give up your extra parking spot for a garden plot?

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: