The stench of fish offal and the screams of gulls: a century ago, the presence of a cannery on the British Columbia coast was unmistakable, even with your eyes closed. Open them and you saw gulls and eagles circling and diving to pluck discarded fish heads and entrails from the ocean around the wooden buildings perched on pilings.

A steady parade of fishing boats navigated the bloodied water to pull alongside the cannery and offload their catches. Inside, an ankle-deep layer of slippery salmon awaiting butcher knives covered the gut shed’s plank floor, and the production line operated at a dizzying pace as ranks of workers scaled, washed and chopped up the salmon, before sealing it in tin cans.

British Columbia’s salmon runs seemed infinite in those days, and businessmen determined to profit from this bounty by turning it into a commodity that could be shipped worldwide staked out their ground along the coast.

In 1918, shortly before the industry began to consolidate, the number of canneries peaked at 80. Now, 100 years later, only a single commercial cannery dedicated to processing wild British Columbia fish remains on Canada’s West Coast. Far from being an archaic relic, St. Jean’s Cannery and Smokehouse is at the forefront of a new era in the province’s fishing industry — an era in which First Nations communities are regaining control of the marine resources that have sustained them for tens of thousands of years.

From the outside, St. Jean’s looks nothing like the canneries of old. Boats, for instance, are absent. Located about a kilometre from tidewater in an industrial part of the southern Vancouver Island city of Nanaimo, it has truck bays instead of wharves for receiving fish. The signage is minimal, but there’s no missing the three-metre-tall can of salmon in front of the cluster of low, metal-clad buildings.

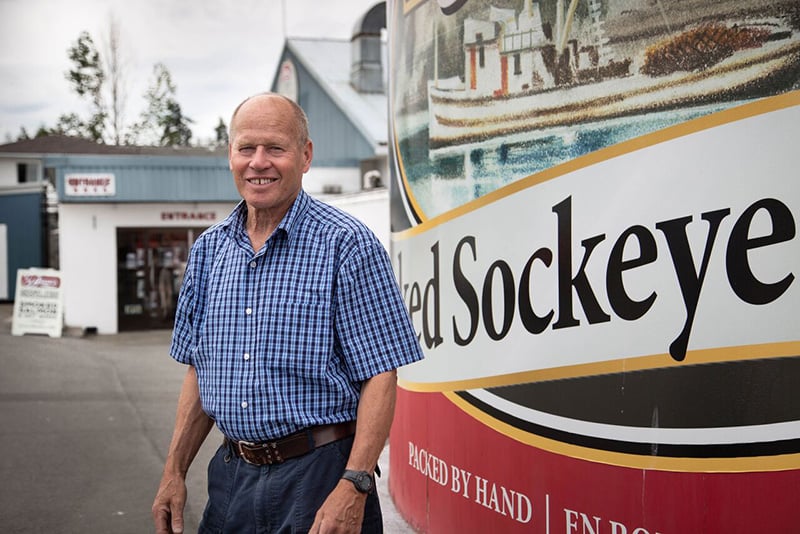

I enter the yard and ask a man wearing blue coveralls, a ball cap and scuffed steel-toed boots where I might find Steve Hughes, the company president. He flashes a grin and points to the can. Sure enough, there’s a door on the far side. Only later will I discover that I was talking to the company’s not-quite-retired former owner, Gerard St. Jean. In November 2015, he sold controlling interest in his family’s business to NCN Cannery LP, a partnership between five of the 14 Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations that call the western side of Vancouver Island home.

Inside the can, which turns out to be a cozy, wood-panelled museum-cum-boardroom, are three people who represent the new face of the business: Hughes, as well as Jennifer Woodland and Larry Johnson, the CEO and president, respectively, of Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood, the First Nations-owned parent company of NCN Cannery.

On one level, the St. Jean’s tale is the story of a business. On another, it’s a social story about change rippling through British Columbia’s coastal communities.

While British Columbia’s canning industry dates back to the earliest days of Canadian confederation, the canning process itself is even older, invented by a French chef in the early 1800s. By 1864, Americans were canning salmon on the Pacific coast. Three years later, Scottish entrepreneur James Syme established a canning operation near the mouth of the Fraser River in what would soon become British Columbia — the first of 223 salmon canneries that have come and gone in the province since then. The most fleeting of these enterprises, like Syme’s, lasted a season or two. The most tenacious, the North Pacific Cannery in Prince Rupert, boasted almost 90 consecutive years of fish processing, starting in 1889 and ending in the late 1970s.

St. Jean’s, launched in 1961, was a latecomer to the canning party and began not with salmon, but with oysters. Armand St. Jean started the business in his backyard, working out of a smokehouse he had built behind his garage. At first, he packaged his smoked oysters, which he called “smudgies,” in plastic bags and sold them to bar patrons around town. By 1964, he had progressed from baggies to vacuum-sealed tins, expanded his line to include oyster chowder and salmon, and set up a dedicated processing facility with about five employees. He also began offering small-lot custom processing to recreational anglers.

When Armand decided to retire in 1978, Gerard St. Jean left his job as a machine design engineer to perpetuate his father’s legacy — only to be pitched straight into the economically stormy 1980s. St. Jean’s almost went under soon after Gerard took over, but just when things looked hopeless, he landed a massive contract to produce canned seafood for the 1986 world exposition held in Vancouver. Expo 86 revitalized the company’s bank account and boosted its public profile allowing Gerard to carry on.

St. Jean’s core business is still canning seafood — primarily from British Columbia waters, but sometimes from Alaska, Washington or Oregon — and oysters and salmon still figure prominently, though the operation is now much more diversified than in Armand’s day. Just how wide-ranging it is becomes apparent inside the processing facilities, a maze of interconnected buildings where rubber boots, blue hairnets and bright-yellow aprons are standard garb.

The original plant was just one room, and this space still houses the main canning line — pumping out as many as 30,000 cans a day during peak production periods. Although today is not a high-output day, there’s purposeful action everywhere within the room. Ten women deftly place glistening pieces of raw tuna into open cans. Nearby, cans of sockeye salmon travel the length of a conveyor, each one receiving a dash of sea salt before its lid is dropped into place, vacuum-sealed and seamed. The rumble of machinery and the hiss of steam venting from the immense retort ovens is a steady cannery soundtrack.

Next door, on the cutting line, half a dozen employees wielding long-bladed knives rapidly reduce whole pink salmon to neat fillets for a corporate barbecue order. In the smokehouse, the air is redolent with spicy scents generated by the hardwoods used to cure salmon, tuna, oysters and mussels. Inside the walk-in freezers, the shelves are loaded with frozen products that include halibut, black cod and spot prawns.

In addition to its own St. Jean’s and Raincoast retail brands, the facility also handles processing for a number of co-pack clients — commercial entities that put their own labels on the finished goods — and thousands of recreational fishers.

While diversification has helped St. Jean’s outlive its competitors, the company’s old-fashioned ethos may be the most important factor in its persistence. In the early days of the industry, every step of the process was done by hand — even the cans were handmade. But as the 20th century rolled out, cannery owners increasingly embraced efficiency-enhancing innovations such as butchering machines and can-filling devices. St. Jean’s, however, has always preferred the human touch, a fortuitous choice that has perfectly positioned the company to take advantage of today’s flourishing foodie culture, with its passion for all things artisanal.

“We’re a hand-pack cannery,” Hughes explains, contrasting this method to mechanized canning, where there’s “literally a giant piston jamming salmon into a can.” Hand filling is slower, but Hughes says the ability to “select only the best stuff” results in a higher-quality product. Consumers, who pay a premium of a dollar or more per can, apparently agree.

St. Jean’s also stands out as the only company putting canned-in-Canada wild Pacific salmon and tuna on grocery store shelves. (Most canned salmon and tuna sold in North America comes from processing facilities located in Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam or Alaska.)

“In general, the canned seafood market globally is slightly down, but we don’t experience that,” Hughes notes. “There was a perception before [that] the garbage goes in the can. We clearly focus on a different end of the spectrum and people are resonating with that, so we see growth.”

When Gerard started contemplating retirement a few years ago, there was no shortage of offers for his company. Yet rather than go with the highest bidder, he chose the one he felt best matched his values and would keep the business on Vancouver Island. His decision to sell to NCN Cannery, the limited partnership formed by the Ditidaht, Huu-ay-aht, Uchucklesaht, Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ (Ucluelet), and Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h’ (Kyuquot-Checkleset) First Nations, was notable on two counts. Just a few weeks earlier, Canadian Fishing Co. (Canfisco) had permanently shut down the canning line at its Prince Rupert plant in northern British Columbia, blaming declining demand for canned salmon and its Alaskan competitors’ lower wages and operating costs. That left St. Jean’s as the last commercial cannery processing wild salmon in the province.

The fact that St. Jean’s was now in First Nations hands was equally significant. First Nations labour was critical to the success of British Columbia’s canning industry, especially in the early days when the region’s non-Indigenous population was so small. The First Nations men who initially supplied all of the fish to the canneries were soon marginalized by discriminatory race-based rules that restricted their ability to obtain independent fishing licenses, but inside the plants First Nations women were always the backbone of the workforce.

First Nations cannery ownership, on the other hand, is almost unprecedented in British Columbia. The only historical exception is a salmon cannery owned and operated by the Tsimshian community of Metlakatla for several seasons in the early 1880s. (In the United States, there are several Native American-owned fish canneries, the largest of which is the Swinomish Fish Co. in La Conner, Washington.)

Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood president Larry Johnson is Huu-ay-aht and grew up immersed in his people’s fish culture in the small fishing village of Bamfield. “All the husbands would be out on seine boats or halibut boats or trollers,” he recalls, while their wives fished from smaller vessels, closer to shore.

“They’d go out and put the lines down, they’d catch fish, they’d bring it home, they’d can it, they’d smoke it” — just like countless generations of women before them. As for the children, “we learned how to clean a fish probably at about six years old.”

Johnson also started fishing with his father around age six and eventually became a commercial fisherman. In 1995, however, he left the fishing boats and began working for the Huu-ay-aht First Nations in treaty negotiations and resource management. His mission has become reconnecting his people to their marine roots and revitalizing their communities through new, sustainable economic opportunities related to seafood harvesting. Helping the Nuu-chah-nulth take the helm at St. Jean’s fit perfectly with this vision. “We saw it as a good investment and that it lined up with our traditional practices and principles,” he says.

And it’s clear that the acquisition is viewed as an alliance, not a takeover. “We didn’t want to change anything Gerard’s done,” Johnson says. Instead, they aspire to build on the company’s success and find ways to integrate their commercial fisheries and community members.

In time, this could include St. Jean’s hiring more Nuu-chah-nulth employees and buying more fish from Nuu-chah-nulth boats, but currently there are constraints on both. None of the NCN Cannery shareholder nations are within easy commuting distance of Nanaimo, and historical circumstances have concentrated their commercial fishing licences on halibut rather than sockeye salmon, the St. Jean’s mainstay. An April 2018 British Columbia Supreme Court decision that affirms the right of five Nuu-chah-nulth nations to catch and sell fish may eventually open up new opportunities for other First Nations. However, none of the plaintiff nations in that court case are part of the NCN Cannery group, and wider applications of the ruling may be years away.

In the meantime, the NCN Cannery members are benefiting from their new relationship with St. Jean’s by gaining access to expertise that is helping them develop their own Aboriginal caught and processed brand, Gratitude Seafoods.

“We want to be able to tell our story through seafood,” Johnson says. “We’re saying we’ve been here since the beginning of time, we’re still connected to our land and resources.”

Although Gratitude Seafoods canned salmon isn’t for sale yet, the new ownership structure at St. Jean’s is already rewriting the historical narrative about the role of First Nations in British Columbia’s fishing industry. Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood CEO Woodland recently met a woman who had stopped by St. Jean’s to collect her custom-processed fish. When Woodland saw her taking a picture of the giant salmon can, she went over to chat. Her response to Woodland’s greeting speaks volumes about the pride generated by the paradigm shift.

“I’m Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h’,” the woman said. “This is ours.’” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Local Economy, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: