“The living fabric of the world ... is slipping through our fingers without our showing much sign of caring.” — Pontifical Academy of Sciences, 2017

We need to pay attention to right whales, because they are dying in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and telling us a story.

The story explains how a docile mammal the size of a school bus is responding to the consequences of rapid global warming driven by the relentless burning of fossil fuels.

Another mammal, Homo sapiens, has caused this chaotic energy mess that now dumps the equivalent of four Hiroshima atomic bombs of heat into the atmosphere or oceans every second.

The right whale crisis is not just a tragic story about ships and nets slaughtering an endangered mammal.

It is a dark industrial fable about shifting food supplies, migration and climate change.

Someone should probably read this story to Jason Kenney, Justin Trudeau or Doug Ford before they are tucked into bed at night.

But those boys aren’t paying attention anyway.

By now you’ve probably seen a news clip or read a few headlines about the horrible deaths of right whales in the St. Lawrence.

Last month, one per cent of the North Atlantic right whale population (only 413 remain on the planet) got rubbed out on Canada’s eastern coast.

They were struck by boats or lacerated by fishing gear. In fact, most right whales perish at the hands of “anthropogenic trauma,” as they have for a thousand years.

The dead included a mother named Punctuation who bore eight calves, a grandfather named Comet, and a young male called Wolverine.

And so the world’s rarest whale species is getting closer to extinction. Most experts say the creatures will sing their death song by 2040.

Right whales used to forage around the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy in summer and birth their calves near Florida in winter.

But now they are venturing into more northern and foreign waters heavily industrialized by ship lanes and fishing activity.

Caught off guard by the rapidity of climate change, the Canadian government hadn’t established any regulations to protect the animal’s lumbering ways until new and inadequate speed restrictions for ships appeared this week.

Any species, pushed by climate change, will start to move once it gets hungry.

Now let’s discuss a thing or two about right whales, a mammal just like humans.

American whalers probably gave Eubalaena glacialis its common name, and for good reason.

Composed of 40 per cent blubber, the animal spends lots of time at the surface and hugs the shore. Those characteristics make the right whale easy to kill or ram with a boat. The animal also floats pretty well once dead.

To industrious Yankee whalers, the right whale made the most convenient and efficient kill. In an orgy of butchering, the whalers nearly exterminated the animal by the 1800s.

Oil from the right whale provided illumination for civilization, and its baleen made umbrellas and venetian blinds.

Philip Hoare writes in The Whale — a book as majestic as its subject — that right whales were once highly fertile. Males sported an eight-foot-long penis and the largest testes of any animal.

Yet today, after a thousand years of relentless predation, the right whale remain the rarest of whale species despite a ban on their killing since the 1930s. Only eight matrilineal lines are left in Atlantic right whales.

Nobody really knows how many tens of thousands of right whales once hugged Atlantic shores.

But there is no question, says one historian, that the animal suffered from “one of the most extensive, prolonged, and thorough campaigns of wildlife exploitation in all of human history.”

Like their hunted ancestors, the surviving right whales still frequent the busiest shipping routes.

Struck by boats and entangled by fishing lines, their numbers continue to dwindle.

And now climate change is throwing the last fatal harpoon, says a sober study that recently appeared in the journal Oceanography.

The right whales have always dined on Calanus finmarchicus, a shrimp-like creature that feeds on algae and plankton off the coast of Canada and in the Gulf of Maine.

But in recent years climate change has shifted the circulation of deep waters in the Gulf of Maine where the rice-sized crustaceans hang out, explains the paper.

Some deep waters have warmed as much as nine degrees, driving away large blooms of Calanus finmarchicus, a subarctic species already living on the margins of its territory.

As a result hundreds of right whales, looking for fat-rich crustaceans, started to meander into the Gulf of St. Lawrence two years ago. No regulations protected their passage.

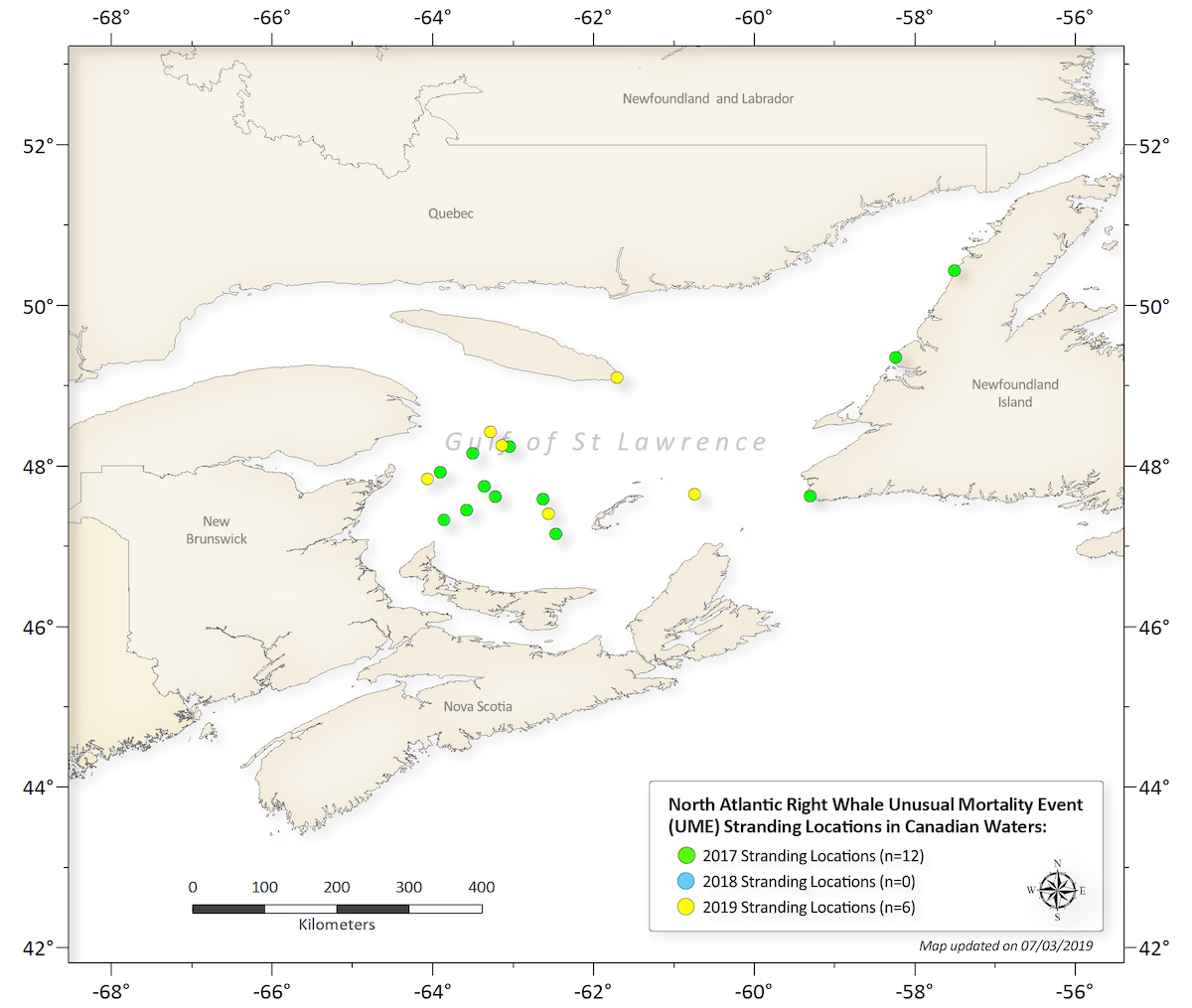

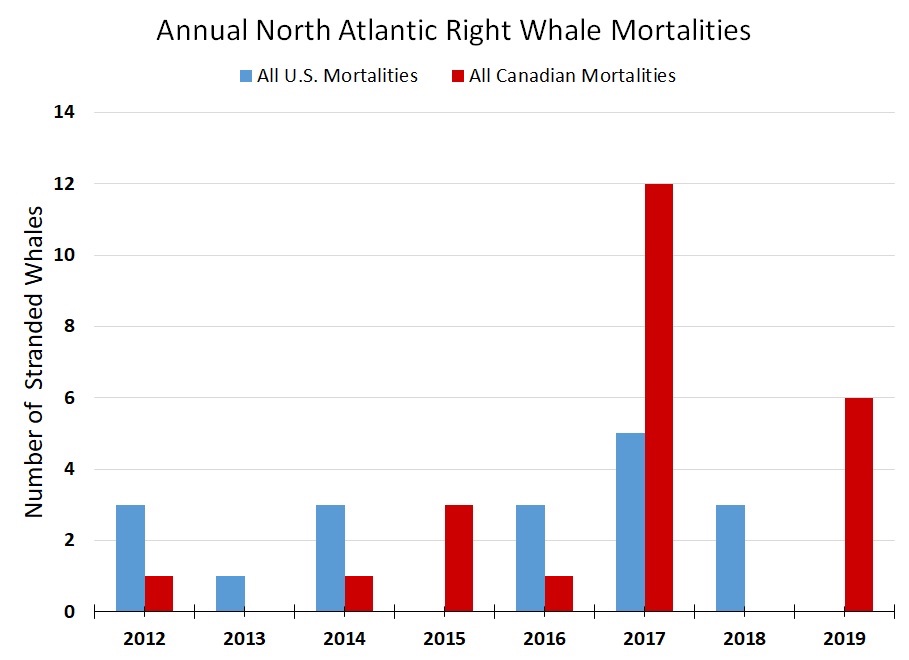

Ships and fishing gear massacred a dozen animals in 2017 alone, along with two other right whales near Cape Cod. Researchers called the deaths an “Unusual Mortality Event,” or UME.

And now half a dozen have perished again this year in the hostile waters of the St. Lawrence, for the same reasons.

“For decades, we have known where and when to find right whales,” wrote Dan Pendleton, one of the paper’s authors and a research scientist at the New England Aquarium.

“Now that paradigm is breaking down, and we’re seeing changes to behaviours that had remained consistent since before people starting observing them.”

Another author of the paper said events were outrunning our awareness and ability to act. “Climate change is outdating many of our conservation and management efforts, and it’s difficult to keep up with the rapid evolution of this ecosystem.”

The omens are not good.

Nearly a decade before the publication of the Oceanography study, Hoare documented how rising temperatures were already beginning to drive the tiny crustaceans north “while warming oceans absorb more carbon dioxide, acidifying the whale’s environment.”

But the Oceanography paper offered another consequential factor. “The right whale population is not healthy, and more time spent foraging may lead to additional mortality, amplifying the challenges this species faces.”

The old ways of reducing risk for a dwindling whale population — such as designating critical habitat or modifying vessel routes — “are built upon the notion that whales will visit the same foraging grounds at the same times each year,” the researchers note.

But climate change has blown a hole in the right whale’s regular schedule by shifting its food supply north into colder waters.

The right whale is not swimming alone in this irregular world, as biological and economic dominoes begin to tumble everywhere.

Take, for example, a mammal species that lives near the Caribbean Sea and the North Pacific. They are called Hondurans.

Drought and crop failures in the highlands of Central America — all related to cambio climatico — have forced them to pray for rain or migrate to new feeding grounds, just like right whales.

Fortunately, there are more Hondurans left in this world than there are right whales.

Another mammal species facing a similar predicament lives at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea.

Faced with drought, war and the lowest wheat production in 30 years, Syrians are on the move.

Like right whales they are showing up in unlikely habitats as far away as Canada.

Some, like right whales, have washed up on unfamiliar shores, dead.

If the right whale nation had a National Intelligence Council (and who knows, they might), Punctuation or Comet might have left behind a memo before they died.

It probably would have echoed what the U.S. National Intelligence Council warned years ago: “The net effects of climate change on the patterns of global human movement and statelessness could be dramatic, perhaps unprecedented. If unanticipated, they could overwhelm government infrastructure and resources, and threaten the social fabric of communities.”

The social fabric of Punctuation, Comet and Wolverine perished on the shores of the St. Lawrence, far from their native feeding grounds.

The right whale is now asking the most distracted and careless mammal on the planet to pay attention.

Sooner or later, more human mammals will find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time due to rapid warming.

Perhaps their deaths on haphazard migration routes will be recorded as the product of “anthropogenic trauma.” ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: