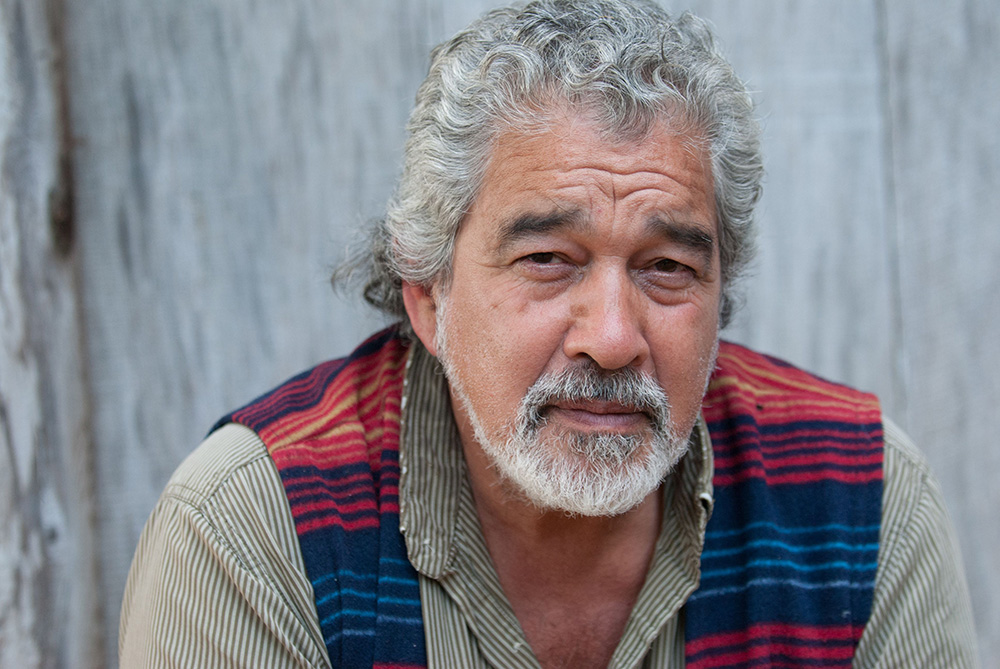

A few days before one of the biggest milestones in the Haida Nation’s struggle for self-determination, I was having coffee with Guujaaw.

We were seated on the patio of Jags Beanstalk cafe in Skidegate, near the southeast corner of Graham Island, the shield-shaped northern base of the archipelago of Haida Gwaii. Guujaaw, the Hereditary Chief Gidansda and formidable former president of the Council of the Haida Nation, was sipping away the sad face shaved into his cappuccino foam. “He thinks I’m grumpy,” Guujaaw said, gesturing to the cafe’s owner, Jags Brown.

Guujaaw didn’t seem grumpy, but like he had something on his mind.

After a 15-minute conversation about climate change (“the jet stream is all out of whack”) and the wonders of Haida canoe technology (old designs — believed to be gifted from supernatural beings — are symmetrical “within a sixteenth of an inch from side to side”), he landed on the heaviest stuff: colonization, criminalization, residential schools.

He recalled being put in jail for two days because he and his sons caught 27 pink salmon without a license on a river where 750,000 were taken by license holders the same day.

“And the reason for that is they wanted to sever those ties to have their way with the land,” Guujaaw said. “It’s gonna take a long time to recover.”

Three days later came a significant step in that direction.

Last Friday, Aug. 13, 2021, the governments of British Columbia, Canada and the Haida Nation announced a new framework agreement that recognizes the nation’s inherent title and rights across the archipelago of Haida Gwaii, which translates to “islands of the people” or “islands coming out of concealment.”

Haida Gwaii is a collection of more than 200 islands forming an area about a third of the size of Vancouver Island and tucked under the Alaska panhandle. It’s home to some of the oldest and rarest plant and animal species on the continent, which the Haida consider their kin. This habitat of ancient rainforest, rugged coastline and surrounding waters teems with shellfish, shorebirds, five types of salmon and more than 20 species of whale, dolphin and porpoise.

On this territory, the Haida have endured a giant tsunami, an outbreak of smallpox that nearly wiped out their population and the onslaught of commercial hunting, logging and fishing that have shipped billions of dollars worth of resources off the islands. Even the remains of Haida ancestors have been literally robbed from their graves.

The first thing a traveller notices when setting foot on the islands is just how remote they are. It takes eight hours to make the 90-nautical-mile crossing from Prince Rupert on a ferry that rarely catches sight of land. Haida Gwaii is home to one of Western Canada's largest populations of bald eagles, half the world’s ancient murrelets, and a host of other threatened and native species from the adorable Haida ermine to the largest black bear in the world (taan to the Haida, or Ursus americanus carlottae to zoologists).

In 2002, the Haida filed a title claim in the Supreme Court of British Columbia that declares authority over the land, inland waters, seabed, sea and airspace of Haida Gwaii. Despite meeting international principles for native claim, Canadian law has required Indigenous nations in B.C. to prove their continuous existence, use and occupation prior to 1846 — the year the British Crown asserted “sovereignty” (or sole jurisdiction) over “British Columbia.” Crown sovereignty is based on the discredited Doctrine of Discovery, which has allowed white settlers to magically become masters over much of the world.

The Haida possess a mountain of oral, written and archaeological evidence that shows occupation and use as far back as 12,800 years ago. The sheer remoteness of their home, like a fortress surrounded by a raging moat, has meant there are no overlapping claims by other nations. The archipelago was near impossible for all but the Haida and their canoes to reach.

Because the Haida have such a strong title claim, the court case has been a negotiation tool in the nation’s back pocket for the past 20 years. It has yet to go to trial — which could send shock waves throughout the Indigenous world if title is granted — but the Haida have never stopped pushing toward that aim.

However, the new GayGahlda “Changing Tide” Framework for Reconciliation unveiled Friday charts an alternative course that prioritizes negotiation over litigation while saying the two can coexist. The crucial part is the starting point. Instead of having to prove title, negotiations will now begin from a place of inherent Haida title and rights, which includes the right to self-government.

“GayGahlda represents an important opportunity to begin the process of Tll Yahda ("making things right") between the Crown governments and the Haida Nation,” said Gaagwiis Jason Alsop, president of the Council of the Haida Nation, in last Friday’s announcement. “By shifting away from the denial politics of the past and moving to a place of truth through acknowledgment of inherent Haida title, a strong foundation for negotiations is established.”

The agreement sets negotiation priorities from forestry and fisheries — which are co-managed by the province and federal government, respectively — to fair compensation from the Crown for past damages. But it also lays out longer-term issues such as food security, language, well-being and climate change. (The archipelago currently runs on diesel but aims to have clean and independent energy by 2023). While title acknowledgment is limited to the terrestrial area of Haida Gwaii, the framework also commits to continued negotiations over marine management.

Recognition of title is not as strong as it being granted by the highest court as it was in 2014 with the Tŝilhqot’in Nation — still the only Indigenous peoples to win a title claim in Canada. Yet the Haida Gwaii agreement is notable because it covers a much larger area than the central B.C. territory of the Tŝilhqot’in. Some are saying the framework could be a model for other nations.

“There is no cookie-cutter,” said Jack Woodward, one of the lawyers in the Tŝilhqot’in case. “But as usual, the Haida are in the forefront in providing leadership, based on their own unique circumstances.”

Jeff Huberman, who’s also worked as a litigator and strategist for Indigenous peoples for more than 20 years, said a lot depends on how the framework is implemented, noting that it’s not legally binding. There’s also a fundamental problem with putting the emphasis on settler society’s recognition of something that Indigenous peoples have known and lived for thousands of years, he added.

“These are their lands, period,” Huberman said. “It shouldn’t be about the extent to which I, as a non-Indigenous Canadian, am willing to go to make space for Indigenous peoples here. It should be about the extent to which they are willing to make space for us.”

The timing can’t hurt the Trudeau government, which just announced a snap election on Sept. 20. In the face of apocalyptic fires and heat, a fourth wave of the pandemic and the uncovering of 1,400 children's graves and counting at former residential schools, the country could use some reconciliation.

“It’s good to see the provincial and Canadian governments rising to the occasion,” said Jisgang Nika Collison, executive director at the Haida Gwaii Museum — which makes up the heart of the stunning Haida Heritage Centre at Kay Llnagaay.

She hopes the impacts will reach beyond Haida-Canada relations. “As much as we want to take care of our little corner of the world, I hope it inspires greater society to take real action on social and environmental justice and responsibility.”

In Haida Gwaii in the days leading up to the announcement, there was a tell-tale buzz in the air. When I requested a meeting with Kii’iljuus Barbara Wilson, a Haida ethnobotanist and representative of the Council of the Haida Nation, she said she was slammed with meetings all week in preparation for a possible election call (which I now understand could have jeopardized the whole thing). When studying maps with local conservationist John Broadhead, he described the island’s political cycles, hinting that another big swing was about to occur. And nearly all of my conversations, whether about cedar or the “illegal” salmon that put Guujaaw in jail, would inevitably wind their way back to title.

“We’ve been negotiating forever, but this is the biggest step we’ve taken,” Guujaaw said. While compensation still needs to be finalized, the nation is already looking at buying back some forest lands and a potential site to relocate the village of Old Massett in the case of sea level rise. “It’s not just a wish list,” Guujaaw said. “We have to make things change.”

His response hearkens back to 2004 when the Haida won their Supreme Court of Canada case against the logging company Weyerhaeuser. The judge ruled that the Crown has a duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous interests when it comes to harvesting timber or transferring forest licenses. Instead of celebrating the news, then-president Guujaaw was pragmatically planning ahead: “Victory is only going to be real if we go out and get it.”

Dale Lore remembers that day well. A man whose personality perfectly suits his name, Lore was the mayor of Port Clements at the time. He had spent the 17 years prior building roads for the timber giant MacMillan Bloedel and then Weyerhaeuser. But when he started looking at the logging plans as mayor, he saw something startling: by the year 2029, the curve for the old-growth timber harvest flat-lined. “The fall-down effect,” Lore said. “They told us there were trees forever, and in the ’60s, it was the truth. We were supposed to take it all. We never questioned it.”

Lore made what might seem an unusual decision for the mayor of a logging community. Worried for the future economy as well as the environment, he opted to help the Haida with their Supreme Court case and partner on the islands’ future. Together with the mayor of Masset — the non-Indigenous community just south of Old Massett — Lore signed a protocol agreement with the Haida that declared Haida title while the Haida ensured that non-Indigenous people could own private property.

Then in a move that was “recklessly brave” in the words of John Broadhead, Lore served as an intervenor in the court case, and later stood on the blockade line against the company he worked for. “I was blockading myself in a way,” Lore said.

That was during the Islands' Spirit Rising protests that flared up in 2005 after the Toronto-based asset manager Brascan announced a $1.2-billion deal to acquire Weyerhaeuser’s coastal operations, including a large forest block on Haida Gwaii. Despite the Supreme Court decision requiring Indigenous engagement over logging and licenses, the Haida Nation had once again not been consulted.

This was 20 years after Haida Elders in button blankets were famously arrested for blockading logging operations on Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island) leading to the national park-level protection of South Moresby, now known as Gwaii Haanas, meaning “islands of wonder.” Lore said he trusted the Haida more than the provincial government to sustainably manage the forests.

Today, he guides tours around the spruce and cedar-hemlock forests he’s helped protect. It’s one of the clearest ways to see traditional Haida forest practices, as well as living cultural artifacts, many of which are pre-1846 and therefore help prove Haida title. Test holes show where Haida fallers checked for wood quality (or “looked into the heart” of the tree), while half-formed cedar canoes, now overgrown with mosses and mushrooms, are a haunting reminder of past epidemics.

The Haida fought hard to regain partial stewardship of these forests. A 2007 land use agreement and 2009 reconciliation protocol with the province followed Islands' Spirit Rising and ultimately allowed the Haida to buy back the contested Weyerhaeuser forest tenure, now known as Tree Farm License 60. Today, the Haida-owned Taan Forest company oversees the area, which is the largest forest tenure on the islands. Forest management decisions are now guided by the 2010 Haida Gwaii Land Use Objectives Order and shared between the Haida Nation and the province. But in cases of disagreement, the province still has final say.

“The Haida don’t have a veto,” said Nang Hl Kaayas Sean Brennan, a former member of the Solutions Table, which was set up to resolve issues of non-consensus. “I hope the new reconciliation framework will help us move toward a place where the province respects Haida stewardship authority.”

What does a Haida Gwaii under further care and control of the people who have lived there for millennia look like in the near future? I saw glimpses on my visit. In the once-thriving fishing village of Old Massett, canoe-shaped street signs feature Haida names. Schools, community halls and shops were built like traditional cedar longhouses, many of them guarded by memorial poles carved for relatives who have passed on to the spirit world.

Inside one of these longhouses, Gin Kuyaas Haida Art Studio and Gifts, owner Kuuyang-Lisa White was looking out the window at Masset Inlet. It’s here that at least 35 marine species have fed and supported her people since time immemorial; the best fishing coincided with the mid-month tide, which is the most dramatic of the extreme tidal changes that sweep this part of the world. The inlet is also where White has spent her entire life watching log barges float past her community filled with spruce, hemlock and cedar that some Haida refer to as an elder sister.

Today, more than half of Haida Gwaii is protected in Gwaii Haanas national park, conservancies and stewardship areas, but most of that is in less productive forest and foreshore. The Land Use Objectives Order from 2010 requires additional conditions for “monumental cedar” — those big and clear enough for canoes, poles and house posts — and culturally important plants within the timber supply area, which makes up the fertile heart of the archipelago. And there’s a Cultural Wood Access Program that, while far from perfect, directs some of those cedars to carvers and cultural projects like White’s shop.

Despite these measures and Taan Forest managing the largest timber area on Haida Gwaii, clear-cut logging is still the norm and cedar has been overharvested for years. The Council of the Haida Nation has tried to balance economics with the environment, but Taan still operates within B.C.’s colonial logging system, which is designed to cut as much wood as possible and cheaply send it to international markets. White said she doesn’t understand why valuable trees are still being shipped off as raw logs when they could be going to more local jobs and construction. “We have to import wood to build our homes,” she said. And as a weaver, she’s also worried about younger cedar that has no specific protections even though it’s essential for bark harvesting.

During the pandemic, while her shop was closed due to restrictions, White joined the Old Massett Village Council to try to help with the community’s unemployment, housing and poverty challenges. But her concerns about logging and climate change haven’t wavered. An estimated 70 per cent of Haida Gwaii’s original ancient forest is already gone.

“It’s not a passion, it’s a responsibility,” White said. “Our people and our lands and waters are all connected. The province is burning down, the water’s drying up, and we’re still clear-cutting old-growth forests when they do so much for regulating the climate and protecting water. The colonial forest industrial model needs to end.”

She sees an alternative future fuelled by environmental research, restoration, carbon credits and low-impact tourism that follows the natural law of Yah’guudang, meaning “respect for all living things.”

“What’s really needed is reciprocity,” she said. “It’s time to give back. The people and the land need to heal.”

On my way out of Masset, I dropped in on Jaalen Edenshaw, Guujaaw’s middle son. He’s a carver and artist who just completed his first canoe. More than a dozen cardboard boxes with red "fragile" stickers fill the boat. Edenshaw said they’re fire extinguishers that he ordered during the recent heat wave.

I asked Edenshaw what he thought about his nation’s new reconciliation framework with B.C. and Canada. “This is just the beginning,” he said. “It changes the relationship we have with them, but not our understanding that this is ours.”

As I listened, I admired the 11-metre canoe, with its smooth sides, curved prow and near-perfect symmetry. I imagined it filled with young Haida, paddling together on a powerful, outflowing tide. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: