New COVID-19 data released by B.C.’s Ministry of Health has revealed an important detail that proves what advocates have been saying for months about infection rates and race: The pandemic is disproportionately impacting racial minority communities.

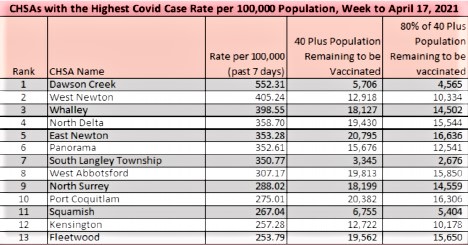

On April 19, provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry presented information about the near-overwhelm of B.C.’s health-care systems due to COVID-19. Within that presentation was one slide that lists 13 communities with the highest case rates across the province.

Besides being the most granular case data the province has ever provided, a closer look at the demographics of each of those communities shows that South Asians made up at least one-third of the population in eight out of 13 areas.

Further, every community in the Fraser Health region with a significant South Asian population is included on the list. The population of West Newton, for example, is 69.3 per cent South Asian.

Experts say that in the absence of race-based data collection, demographics around ethnicity in these hotspots might be the closest B.C. can get to identifying how the pandemic disproportionately impacts racial minority communities.

“If we take a look at the demographics of the communities, we can see what we have already suspected, which is that people who are working in essential work — frontline jobs, predominantly from racialized and marginalized communities — are being affected by the pandemic,” said Kulpreet Singh, founder of the South Asian Mental Health Alliance.

“This is something that’s been replicated across the board in other cities around the world, especially if we look at cities where they have disaggregated data. It’s not surprising to see that here as well.”

Singh, who lives in Surrey, says the surge in cases and disproportionate impact the virus has had on South Asian communities could have been mitigated had there been race-based data collection, as well as language-specific and culturally relevant outreach, from the government at the outset.

He is one of many people and groups across B.C. that have for months been calling on the government to collect information about how the pandemic has been affecting racial minority groups — requests that apparently fell on deaf ears.

In September, B.C.’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner asked for new legislation to ensure the collection of disaggregated demographic and race-based data in order to reveal inequities in the health-care system.

In an interview with The Tyee, B.C. Human Rights Commissioner Kasari Govender says her recommendations were accepted by both the province’s attorney general and the parliamentary secretary for anti-racism initiatives.

This means there is a commitment from the province to introduce legislation that will allow the collection of race-based data in the future, but it won’t come quickly enough to weaken the blow that COVID-19 has delivered.

“The benefit of collecting race-based and other disaggregated data is that we can better target our policies [and] government responses to the real lived experience of people in our communities,” said Govender. “What that means is we can do things like target vaccine rollout.”

She used the example of First Nations people across B.C., and how the province rolled out its vaccination plan for Indigenous Peoples in a much quicker and more efficient way than for the rest of the population, because it knew about health inequities that have led to higher risks among those groups.

All Indigenous adults were able to book their COVID-19 vaccine by the end of March. Meanwhile, in the age-based program for the rest of the population, only people aged 60 or older were being sent booking invitations as of April 23.

“That shows how understanding data can help us to target policies to better address the real lived experiences that people are having,” said Govender.

One of the challenges of collecting and then releasing race-based data is making sure it does not perpetuate racism against communities where cases are on the rise.

There are several reasons why COVID-19 may have found a stronghold among South Asian populations in the Lower Mainland.

South Asian communities have had high numbers “because of the correlation with essential workers and the fact that many South Asian Canadians are working in these kinds of high-risk positions at the frontlines of COVID,” said Govender.

“These are the results of some of the policy decisions that we’ve made, and we need to see the connections here in order to be able to properly address that.”

In the absence of race-based data for racial minority groups, it took a major third-wave surge in predominantly South Asian communities before the province decided to implement a targeted vaccination program in those areas in late April.

Last week, provincial health authorities set up clinics to administer doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine in the 13 hotspots identified, but the province is running low on doses.

When asked how long those communities have had the highest rates of transmission, a health ministry spokesperson was unable to answer.

“Throughout the pandemic, different neighbourhoods have seen increased rates of COVID-19 transmission at different times,” they said in a statement to The Tyee.

According to Singh, a lack of disaggregated race-based data is just one of several systemic issues impacting the province’s ability to deliver equitable health care to marginalized populations during the pandemic.

In addition, there is a serious lack of language interpretation services at government press conferences, and little outreach done by the government to engage with minority communities.

“I understand that that requires more resources, but it would also have drastically better health outcomes for people because the uptake would be better,” said Singh.

“I know that it’s difficult to change [these systemic gaps] in short order. But this was the time to do it. Within this pandemic, within this overdose crisis, when we’re looking at health emergencies across the province, this was the time to quickly pivot and take actions that would help generations of marginalized and racialized people,” he said.

For now, Singh says the gaps left by government are being filled by South Asian media outlets — which have been delivering COVID-19 updates and analysis in different languages — and by conscientious community members finding creative ways to get key messaging across.

Dr. Madhu Jawanda is one of the leaders of the South Asian COVID-19 Task Force, a group that has been working since November to create translations, infographics and other innovative ways to communicate government messaging in different South Asian languages to residents in Surrey and beyond.

As a family physician in Surrey, Jawanda feels like she has two jobs these days. She, along with about 30 others, work as volunteers to keep their community informed through the task force.

The group has never received funding from provincial or regional health authorities.

At one point, Jawanda says the group requested a nominal amount of $5,000 from the Fraser Health Authority to create a video that would promote culturally relevant messaging about the pandemic for the South Asian population.

“The head of the Fraser Health Authority board told us verbally [that] this was not possible,” said Jawanda. “We respectfully accepted this. I’m sure they have their reasons, but we were not made aware of those reasons.”

In a statement to the Tyee, a spokesperson for Fraser Health says the authority works collaboratively with the South Asian COVID-19 Task Force to share materials and information with communities.

They did not answer the question of why the task force was not provided with the requested funds.

Nevertheless, Jawanda says the task force took the rejection in stride and members were happy to continue working voluntarily as they have been for months.

For her part, as a member of the South Asian community and a health-care worker, Jawanda says the workload and time apart from family has taken a heavy toll on her mental health.

Her parents, aged 81 and 84, live in Edmonton and are fully vaccinated, but despite not having seen them for more than a year, Jawanda says she won’t visit them until the province says it is safe to travel.

“I will listen to what Premier [John] Horgan says, and when I am able to travel and it’s safe, I will see them, knowing that every conversation I have with them could very well be the last, given their ages,” she said. ![]()

Read more: Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: