In the fields and warehouses and offices and kitchens and factories of Canada, about one in 60 employed people is someone like Carlos — a temporary foreign worker. Carlos, a muscular man with a wife and child at home in a small town in Guatemala, has for most of the last year done many jobs needed on a farm in Delta, B.C.

“I came to Canada in search of a better life,” he told The Tyee, requesting that his last name not be shared. “Working in Delta means I can support my family. There’s no better feeling than that.”

Then the pandemic hit. As the crisis has unfolded, its effects on visiting workers like Carlos have occasionally flashed into view, such as when COVID-19 spread in their workplaces, including a Kelowna farm and two Alberta meat plants. A recent Tyee article related challenges faced on Lower Mainland berry farms.

But most of the time for British Columbians, the daily diet of news about living isolated, the steady charting of our own pandemic drama, has made it easy to forget how intertwined we are with people who call other countries home.

Our very sustenance depends on them. In 2019, B.C. approved 32,031 temporary foreign worker positions, of which 13,252 were agricultural workers. In return for making our society run, Carlos and other temporary foreign workers ship money home and occasionally return there themselves, as the program requires. Then the cycling of human labour and cash resumes.

The pandemic has interrupted that flow for many. In February, Carlos left Canada to visit his family in Guatemala, intending to return a month later and go back to his job at the Delta farm. But those plans fell apart as Canada put new measures in place to fight the virus — and Guatemala began to brace for its arrival as well.

Carlos was stuck, unable to leave his town, let alone his country. “At first it was nice to be able to spend time with my wife and daughter. I hadn’t seen them since I left Guatemala last year. But as days went by and travel restrictions were imposed, I began to worry if I would be able to return to Canada this season,” he said.

Since its first COVID-19 case on March 13, Guatemala has seen the numbers rise to 7,055 cases and 252 deaths. In a largely rural and low-income nation with a large Indigenous population, the pandemic is playing out in ways very different from the Canadian experience, straining a thinly spread health system and for many compounding the hardships of subsistence living.

As B.C. “reopens,” the virus closes in on a nation, 5,314 kilometres away, which shares some of its people to help build this province’s future. This is why The Tyee begins today an occasional series focusing on the pandemic’s effects on Guatemalans here and in their home country.

We have tapped the expertise of TulaSalud, a B.C.-based charitable organization that has supported rural health workers in Guatemala since 2002. TulaSalud is a project of Eric Peterson and Christina Munck, who also founded and run the Hakai Institute here in B.C., and who provide significant funding to The Tyee.

This series, produced under the independent editorial control of the Tyee, draws upon many sources, including those found with the help of TulaSalud.

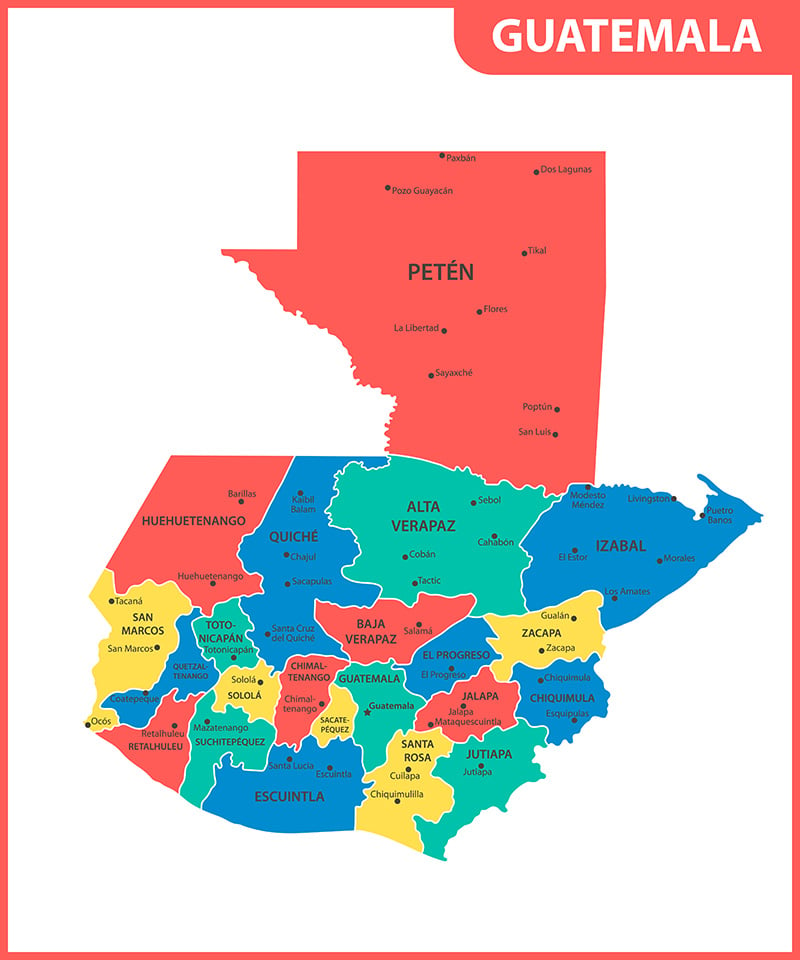

Guatemala, just south of Mexico, is a nation one-ninth the size of B.C., with a population of 17 million. Divided into 22 province-like departments, much of the country is mountainous, lushly green and inhabited by descendants of the Mayan civilization that rose nearly 4,000 years ago and stretched, on a modern map, from western tips of what is now El Salvador and Honduras into Mexico.

In 1954, the United States backed a military coup against Guatemala’s democratically-elected president who was opposed by multinational corporations operating plantations there. In the 1980s, the U.S. again backed military regimes in a “scorched earth” campaign, rife with civilian human rights atrocities, while fighting insurgents pressing for agrarian land reform. The shooting ended in 1996, but the social scars persist.

As COVID-19 cases grew in March, Guatemala’s President Alejandro Giammattei ordered swift and tough measures: foreign as well as regional and municipal borders closed, fines for citizens not wearing masks in public spaces, strict curfews from 4 p.m. to 4 a.m. and, in early May, a country-wide lockdown lasting 72 hours and confining people to their homes.

After shutting its borders briefly to students and workers with visas, Canada updated its travel exemptions on March 20 to once again permit them. There are no reports of Canada sending temporary foreign workers with valid permits home during the COVID-19 outbreak.

The U.S., meanwhile, began deporting Guatemalan migrants. In mid-April, a number of them tested positive for COVID-19. Giammattei’s response was to order more than 230 arriving deportees from the U.S. be held in mass quarantine at a sports centre in the capital. Contrary to social distancing protocols, rooms were packed with about 20 beds and bunk beds each separated by a single metre.

“We don’t want to be here, we prefer to quarantine at home,” said a man named Daniel at the sports centre, who arrived from Brownsville, Texas, along with 108 other Guatemalans. “We feel at risk here.” He said that while his temperature was monitored multiple times a day, he was not tested for the virus.

Carlos avoided such quarantining and the gauntlet of risk it posed. And as he hunkered down in his department of Chimaltenango, he remained uninfected. But like a lot of workers returning home, he faced fear and anger rather than a welcome.

“People, and friends, told me, ‘You’ve come from abroad, you’ve come to kill me. You’ve come to infect us.’ Sometimes I would tell my wife I prefer to stay indoors and not go outside. I don’t want people to give you grief later,” he said. “What people forget is that you’re only abroad because you need the money to improve your condition economically because the reality in Guatemala is horrible.”

Carlos’s experience has proven all too common. Workers from the U.S. returning to towns in the department of Quetzaltenango, in Guatemala’s western highlands, say locals vowed to burn their homes or murder them. In one town, residents threatened to set fire to buses arriving at a temporary migrant shelter.

The fears are stoked by the fact that over 100 Guatemalans back from the U.S. have tested positive for COVID-19. But even those showing no signs of infection “suffer threats when they arrive in their towns and villages because there’s a lot of misunderstanding about the virus. Communities have different reactions and many workers have received death threats, and their families have received threats,” said Byron Cruz, who came to Vancouver as a refugee from Guatemala many years ago.

He now works as organizer and outreach co-ordinator for the BC Federation of Labour's Health and Safety Centre's Migrant Worker Program in Vancouver and is an active member of the Sanctuary Health collective and Migrant Rights Network.

The same fears and misunderstanding about COVID-19 stalk Alta Verapaz in north central Guatemala, the poorest department in the country. Claudia Tut’s job there is to educate people about how the virus is spread and how to prevent it, and to monitor for infections in order to be the first line of care.

Tut is one of two auxiliary nurses who are the only health professionals in the village of San Juan Chamelco. From her base, she travels hours on foot to surrounding communities to make sure those returning to the area are following quarantine restrictions. She does so without any protective gear.

“I have to buy masks with my own money, because we haven’t received enough from the hospitals and health centres,” she told The Tyee. “Without this [equipment] I am risking my life to take care of people who could have the virus, who could have brought this from abroad.”

In Alta Verapaz in recent years, subsistence farming has been pushed aside by palm oil plantations, adding pressure for people to leave and try their luck abroad. Between 2018 and 2019, the number of Guatemalans apprehended at the Mexico-U.S. border more than doubled, reaching over 50,000. Most have been deported.

The economic hardships they’ve faced upon their return have only grown with the arrival of the coronavirus. While the government claims its draconian lockdown orders have slowed the spread of the virus, the stringent measures carry their own deadly potential in a country so poor. “It’s really impacting those who have to work to survive, day to day,” said Cruz.

Cruz calls the Guatemalan government’s measures “rash” for not taking into account how minimal the safety net is for so many citizens. “These decisions have meant little time to adapt, and people with low resources are suffering as a result. There’s a lot of people without work or who are unable to work.”

Scarcity of food is another problem. The restrictions make it difficult for small farmers to tend their crops. A lot of produce is being lost.

“What’s more,” said Carlos, explaining what life has become in his part of Guatemala, “roadblocks mean smaller shops in remote regions aren’t being restocked as often. And this lack of supply is driving prices up, so people can’t afford the same things anymore.”

In the south central region of Guatemala that includes departments Chimaltenango and Sacatepéquez, those experiencing hunger have put up white flags at the front of their houses to ask for help. They are hunkered down in the part of the country hardest hit by the pandemic so far, with about 70 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in Guatemala.

If the lockdown across Guatemala was designed to keep the virus from moving around, it had the same effect on Carlos. He longed to make his way back to B.C. where work awaited. He was happy to learn, in late March, that Canada had greenlighted the return of workers in his program.

But at the time he faced a problem shared by many Guatemalans wanting to leave. They found it difficult to make their way to one of the country’s two international airports. And as fears about the economic impact of the pandemic spread, some communities began requiring those returning or leaving to pay a fee some could not afford.

As a result of such obstacles, “most of the workers that went back to Guatemala for vacation in December have not been able to return to Canada. The impact has been huge,” explained Cruz in mid-May. The week before, only one flight from Guatemala had arrived in B.C.

Farmers in B.C. waited eagerly to put Carlos and others from Guatemala back to work in their fields and greenhouses. In Delta, four farms employ Guatemalans almost exclusively, said Cruz. “Thousands come every year across Canada, and without them, who’s to say what will become of these farms?”

But a cloud loomed over such operations. At the end of March, a COVID-19 outbreak at Bylands Nurseries, in West Kelowna, raised alarms about living conditions at many farms and a lack of federal oversight.

After two workers were confirmed to have contracted the virus, widespread testing at the farm revealed a total of 23 workers had been infected. The resulting headlines served as a reminder that in travelling back to B.C., temporary foreign workers trade one set of risks and vulnerabilities for others.

“This is a community with less rights,” Cruz said of those who toil largely out of view of Canadians. “These migrants come with a lot of fears, from a situation of extreme poverty, and they know that if they refuse to work in unsafe conditions, there are many other Guatemalans who would be willing to replace them.”

A new report by the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change documents abuses faced by migrant farmworkers in Canada, including firing threats, wage theft, inadequate housing during quarantine and racist abuse. As reported in The Tyee today, the authors of the study call for an end to the two-tiered system of rights and benefits created by the temporary foreign worker program, urging instead granting workers like Carlos permanent resident status in Canada.

On May 11, Carlos finally arrived in Richmond. He was checked into a hotel where he quarantined for two weeks with 32 other temporary foreign workers from Guatemala. Now he is back at work on the farm in Delta, glad to be supporting his family back home even as he knows financial stability could cost his health.

“My family depends on me,” he said. “They depend on the work that I do here. I am glad to be able to go back to the farm. Right now, this is the best way I can help them. But I worry about my health, and about theirs back home.”

Next in this occasional series, we shift our attention to rural Guatemala, and how the battle against the coronavirus is being waged there. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: