When Krystal Cozier asked her daughter’s Grade 1 teacher about plans for Black History Month in February 2019, the answer surprised her.

There were no plans.

And she was just as surprised to be asked to teach a room full of six and seven-year-olds about the history.

“To know that nothing is being taught to students is very upsetting,” said Cozier, who, along with her young daughter, is of African descent.

“Because if my daughter is going to be growing up here and she can’t be comfortable in her skin, or if every time she goes to school and she has her hair out in an afro and kids are looking at her like, ‘Oh my God, what happened to you?’ — how is she supposed to feel?”

But that’s likely to change. This week — just days after the death of Minnesota resident George Floyd at the hands of police — B.C. Education Minister Rob Fleming said Black history would be added to the province’s school curriculum.

“I’ve written a letter to the B.C. Black History Association to make this, if you will, a teachable moment, how we can strengthen the curriculum ties to learn about the multicultural history, including the history of the Black community in British Columbia,” Fleming said at a press conference.

In an emailed statement to The Tyee, Fleming went into more detail.

“A central element of B.C.’s provincial curriculum is to encourage all students to be socially aware and to value diversity within their communities,” he wrote. “Young people are watching events unfold in the United States since the police killing of George Floyd and the expressions of solidarity in Canada and around the world. With systemic racism still prevalent in Canada and B.C., many young people want to know what can be done to challenge this and how to make change.”

Fleming said the ministry would also address racism in schools through its ERASE strategy which has focused on bullying and other issues.

The changes would be welcome for Cozier and her family, who moved to the Lower Mainland from Toronto just over a year ago. They first enrolled Cozier’s daughter in the New Westminster school district before transferring to the West Vancouver school district.

Unlike the Greater Toronto Area, where 7.5 per cent of residents identified as Black in the most recent census, just 1.2 per cent of people living in Metro Vancouver self-identified as Black.

The Vancouver school district was already working to develop a high school course on the history of people of African descent in the city, province and country. The district has not provided a timeline.

Before the declaration of a provincial emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Yasin Kiraga, co-founder of the African Descent Society BC, said he hoped the content would be covered in Vancouver schools as early as this September.

The society is helping create the course, and is just one of the organizations emphasizing the need for more curriculum on the lives of Black or people of African descent in B.C., both past and present.

“It is not only for Vancouver, but for British Columbia schools,” said Kiraga, who, like Cozier, prefers the descriptor “of African descent” to “Black.”

The material will go back to the origins of people of African descent settling on these lands, beginning over 400 years ago in Eastern Canada and 162 years ago in B.C., said Kiraga, who developed a curriculum on the topic with American historian and educator Larry N. Davis.

Their curriculum was passed onto the school district, which is in the process of getting approval from its own curriculum committee for the new course to be created and delivered in the district.

“All of this history is not known,” said Kiraga. “But there is a lot of interest among the students, teachers and school board.”

School trustee Jennifer Reddy was not aware of the development of this course, but in an interview with The Tyee she shared her personal views on the need to include the histories and present-day experiences of Black people in the school curriculum.

“Many young Black learners have come to committee meetings, have actually sent letters about not being able to see themselves in the stuff they’re learning in classes,” said Reddy.

“It’s really needed a) at a young age, and b) because young people aren’t seeing themselves depicted at all, or they’re depicted negatively. Especially in texts that still reference negative images of Black people in history, or American versions of Black people in history.”

‘Why isn’t anyone learning my child’s culture?’

Cozier accepted the request from her daughter’s Grade 1 teacher and recruited another parent of African descent to help design and deliver a lesson during Black History Month in 2019. It covered the history of Canadians and Americans of African descent.

“We talked a little bit about slavery, we talked about racism, and then I brought up the pan-African flag and what the three colours represent,” she said, adding the students participated in group matching games and art projects.

“We spoke about cornrows and braids, and how they’re significant because slaves would put designs in their hair that would represent maps they needed to escape. They also would do cornrows and hide rice grains in them so that they would have food as they travelled.”

But this February, when her daughter’s Grade 2 teacher at her new West Vancouver school asked Cozier for help teaching the class about Black History Month, Cozier said she was not interested.

“This time I was a little bit more annoyed: is this going to be every year, every teacher I’m going to have to ask, ‘What do you guys do for Black History Month?’ And then I’m going to get the same response?” she said. Her frustration is not so much with the teacher as with the education system as a whole, she added.

“You live in Canada, which is very multicultural. So, if you’re teaching my child about everybody else’s heritage and cultures, why isn’t anyone learning about my child’s culture?”

Unlike French, Indigenous and Chinese history, the history of people of African descent is not an explicit part of the B.C. curriculum.

When Cozier contacted her district’s superintendent, she was told it was up to teachers whether they wanted to teach about the history of people of African descent in the region.

Kiraga said some teachers do make the effort. “They’ve been very active in advocating for the teaching of Black history.”

He visits classrooms across the Lower Mainland and on Vancouver Island at the invitation of teachers, delivering people of African descent history lessons to students from kindergarten to post-secondary. Last year he visited 27 schools; so far this year he’s been to 25.

Students are interested in the topic, he said. “Everyone from elementary to high school wants to attend, to see, to hear.”

Kiraga also leads walking tours of Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood. “If you combine the walking tours I have organized in Strathcona from Jan. 31 of this year until the end of February, I had hundreds of schools — over 2,000 students — that came.”

Leaving curriculum content to the discretion of teachers too often results in the history of people of African descent being left out, Kiraga said, adding to the misconception that people of African descent have had only a recent and small role in the province and country’s history.

Hundreds of years of settlement

Kiraga, along with people behind the Afro-Multicultural Talent Show in Surrey and from the Centre for Integration of African Immigrants in New Westminster and the African Arts and Culture Society in Victoria, began meeting with provincial MLAs in 2015 about creating a history course and curriculum.

The idea was met with excitement, Kiraga said. But when the BC Liberals lost the 2017 election the group had to start over. The current NDP government was also supportive but directed them to work with a school board on what’s known as a board/authority authorized course. The approach lets boards create courses to meet community needs, subject to education ministry approval.

Once a board/authority authorized course is developed, other districts are free to pick it up or create their own version.

Kiraga says he chose to work with the Vancouver School Board because of its large student population and the rich history of people of African descent in the region. But he would like to see the course taught across the province, with curriculum about the history of people of African descent injected into every grade. The first unit of Kiraga’s draft curriculum, which he gave to the district in the process of working with them towards developing their own course, challenges the assumption that people of African descent only recently began arriving in Canada. It notes enslaved people were brought to what is now known as Eastern Canada over 400 years ago.

“That was the beginning of African-Canadian migration,” said Kiraga.

But the majority of the curriculum focuses on the introduction and presence of people of African descent in B.C.

“The curriculum is designed to help teachers understand the history of people of African descent from the historical point of view: their contributions, their experiences,” Kiraga said.

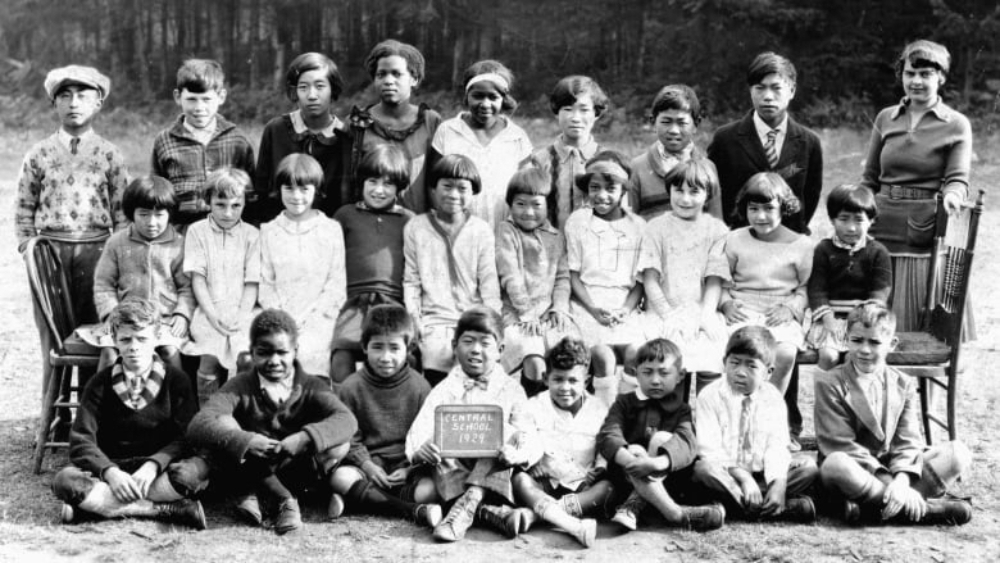

The initial migration to B.C. began in 1858, when the first wave of African-American settlers came to Vancouver Island and Salt Spring Island. When California refused to grant formerly enslaved people citizenship, hundreds of families of African descent accepted Gov. James Douglas’s invitation to settle in the colony.

Another separate wave of settlers of African descent to the Lower Mainland began in 1859.

Racism did not stop when they crossed the border, however. Settlers of African descent faced opposition from future B.C. premier Amor De Cosmos, who campaigned against the African descent population through his newspaper, the British Colonist. Settlers of African descent were banned from some public gatherings and private businesses on Vancouver Island. When the U.S. Civil War ended, many returned to America.

The draft curriculum includes subsequent waves of migration, from the 1900s to the recent arrival of 50,000 asylum seekers, many of African descent, who crossed the border from the U.S. into Canada, fearing deportation under U.S. President Donald Trump.

More work ahead

The Tyee requested an interview with Raman Gill, the Vancouver school district’s resource teacher dedicated to anti-racism support and education, who along with other VSB staff has been working with Kiraga and others on developing the stand-alone course.

The district said Gill was not available.

A district spokesperson emailed a statement saying details like what grades the course could be offered in and when the program could be used in schools are still unknown.

“Once procedures are verified by the... course development team, course authors will be identified to develop the course proposal,” the statement read. “Once a course is developed and approved, it is then added to the curriculum options at schools according to timetabling and student interest.”

The statement also highlighted several different Black History Month events the district held in February, including the formation of a Black students’ union and a professional development day dedicated to educating teachers on integrating the history of people of African descent into their lessons.

Trustee Reddy says the changes must not stop at including one course on the history of people of African descent in B.C.

“In any course, part of a decolonizing framework is looking at who you uphold as the experts or authors of our time, and a lot of our core readings are not written by Black authors or experts,” she said, adding any curriculum changes should coincide with recruiting and retaining Black teachers.

“That’s where I think it’s less about just teaching Black history or Black curriculum, but actually really digging deep to think about: how does it show up in math? In science? Are we showing videos of more white or Asian men talking about science, math and engineering? Or do we centre Black women talking about the same content? And those are the subtle and very implicit ways that racism shows up.”

‘It has to start when they’re younger’

Cozier grew up in the Greater Toronto Area where her school acknowledged Black History month with all-grade assemblies, student presentations and performances and posters in the halls about notable Canadians of African descent.

“I went to a predominantly Jewish school in Vaughan, Ont. Everyone was Jewish, but they would still do Black history,” said Cozier, adding every February the school asked students of African descent if they wanted to perform or make a presentation to the school.

“So I would love, if my daughter was open to the idea, for her to get together with some students where they would be called upon to present or just do something for Black history.”

Cozier’s daughter, now eight, made her own presentation to her classmates in February about Viola Desmond, a Nova Scotian of African descent who made history as a civil rights advocate, a beauty industry leader and entrepreneur, and one of the few women other than Queen Elizabeth II to appear on Canadian money.

Both Cozier and Kiraga would like education on the history of people of African descent to be mandatory in primary and elementary grades. Cozier would also like to see mandatory Grade 9 and 10 courses include the history of people of African descent in their community, province and country.

“It has to start when they’re younger,” said Cozier. “Because I feel like as you get older, you have the choice as to whether you want to take in the information or not.”

Cozier is happy change could be coming to the curriculum in Vancouver. But her daughter attends school in West Vancouver, and if there isn’t a change in the curriculum by the time she is entering high school, Cozier is considering moving her family back to Toronto.

“If it’s going to be a thing where I have to fight for her to feel comfortable, then I don’t want to have to do that all the way into high school when I know that if she goes back to Toronto, she’s going to be with people that are like her, people who understand her, where she’s not going to have to explain herself all the time.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: