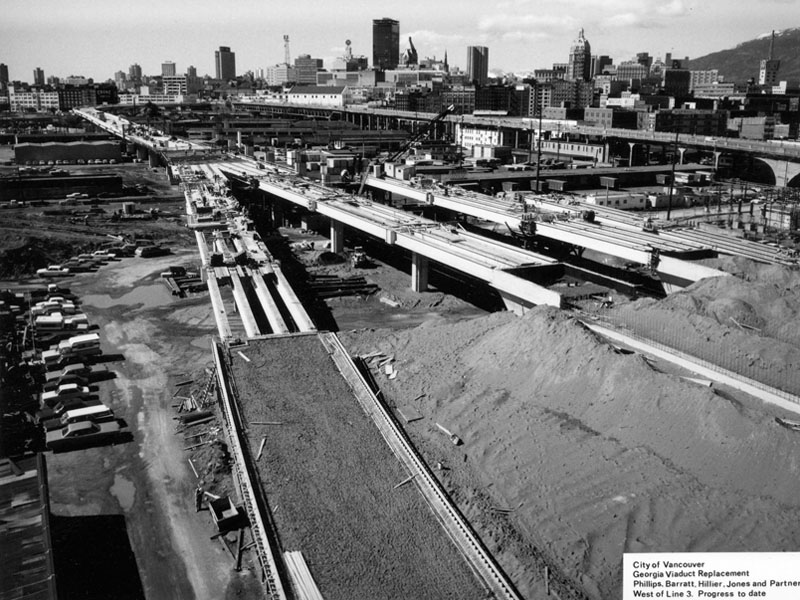

The elevated freeway to Vancouver’s downtown waterfront would’ve been eight lanes, linking the Trans-Canada Highway with Carrall Street and carrying thousands of drivers from the suburbs into the heart of the city centre.

It was never built.

The fight against this state-sponsored “urban renewal” is a defining chapter in Vancouver’s history. The city wanted to bulldoze a section of the inner city for new housing and a network of freeways. It was home to many immigrant communities: Chinese, Japanese, Italians, Jews and the city’s only black community, Hogan’s Alley.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, residents of the Strathcona neighbourhood resisted. They successfully lobbied the federal government and funding for urban renewal was halted. The city, however, still hoped for freeways, and in 1972 built two viaducts intended to be part of a massive interchange.

At the grand opening of the viaducts, protesters clashed with city officials.

“I remember bringing children and seniors and placards and we stopped the mayor’s motorcade,” said Shirley Chan, an instrumental neighbourhood organizer who was in her 20s at the time. “He had to get out to walk the viaducts instead of riding across.”

The federal funding for freeways never came. However, the viaduct project did its damage. Homes of immigrants and cultural groups were demolished to make way. This was a common strategy of mid-century modernist planning: demolition and redevelopment on a large scale, fueled by public dollars.

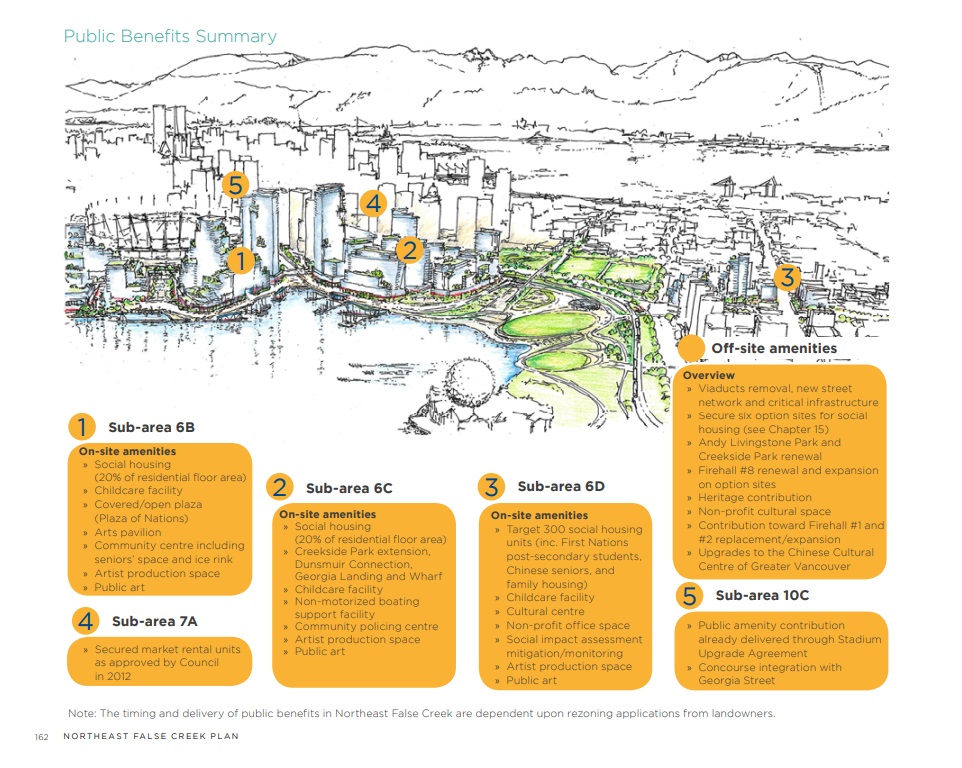

Today, Vancouver has a new plan for northeast False Creek, one that the city’s planning chief has called “the next generation of Vancouver building.” There will be market and non-market housing, shops, parks and childcare, with flourishes like rooftop gardens and terraces. And after over four decades, the viaducts will be coming down.

The development of False Creek has had a long history in Vancouver. The south is representative of the hippier 1970s desire for a mixed community of condos, co-ops and social housing at medium density; 80 per cent of the land is owned by the city itself and leased to tenants. The north is representative of the 1980s when Vancouver was branded as a global city: a high-density residential and commercial area built around a sports stadium and the site of Expo 86.

We now arrive at the development of northeast False Creek, the last undeveloped part of the waterfront. The city aims for the new community to reconnect neighbourhoods that were severed from the rest of Vancouver. There are controversies too, such as the yet undecided route of the new road network that will replace the viaducts. Work on the area’s new street networks could begin as early as late 2018.

But aside from the area’s physical transformation, Vancouver faces a challenge: how does the city make amends for an area where it displaced marginalized people only a few decades ago?

‘Slum clearance’

When Randy Clark’s parents divorced, his mother decided to leave San Francisco with her five children and move to Vancouver to be with her parents. The year was 1965. Clark was 12 years old.

Clark’s first Vancouver home was his grandparents’ house at 230 Union St. It was at the edge of Strathcona, just south of Chinatown and northeast of False Creek.

His grandparents had deep roots in B.C. They descended from the province’s first black settlers, part of 400 families who moved from California to settle on Salt Spring Island at the invitation of Vancouver Island Gov. James Douglas in 1858. (Douglas’s mother was African Creole.)

It was a warm, culturally diverse area; their block was home to the Hogan’s Alley community. But despite the sense of community, Clark had questions about his neighbourhood.

“When we moved to the area, I couldn’t figure out why it was so decrepit,” he said. “Garbage wasn’t picked up. A lot of buildings were not occupied. The city used to clean Union Street by spraying an oily liquid on the street and it smelled like creosote.”

Urban renewal had already begun by the time Clark arrived in 1965. As early as 1949, a UBC study proposed the modernization of Strathcona through “slum clearance.”

In 1959, the City of Vancouver planned the “comprehensive redevelopment” of Strathcona. Two-thirds of the neighbourhood’s old homes would be demolished; social housing, new townhouses and apartment buildings would take their place. Under phase one of the Strathcona development (1961 to 1967), 1,600 people were displaced from 28 acres of land. Under phase two (beginning in 1965), 1,730 people were displaced from 29 acres of land.

“When word started to get out about this huge development, most of the black community had dispersed,” Clark said. “It didn’t happen overnight. Most of those families had moved east to East Vancouver or Burnaby.”

The black community flourished along Hogan’s Alley in the 1920s. It was close to the railway station, where many black men worked as porters, a reasonably well-paying job. The African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel was a community hub; Clark has a church directory from the 1950s with over 400 listings of families like the Collins, the Holmes, the Howards, the Kings and the Woods. At night, the area was known as a red-light and entertainment district, home to midnight eats and jazz. Among the visiting performers were stars like Duke Ellington, Sammy Davis Jr., Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong.

But once the city targeted the area for redevelopment, Hogan’s Alley gradually declined.

Clark’s grandparents’ restaurant was one holdout that was a remnant of its heyday: Vie’s Chicken and Steaks, open from 5 p.m. to 5 a.m.

“Earlier in the evening, there’d be a rush of people wanting to get their meal and going somewhere after,” he said. “At 12 o’ clock at night, when the entertainment places finished their last show, there’d be people coming into the restaurant who had just performed.”

On the menu, of course, was chicken (half-chicken portions) and steaks (T-bone, porterhouse, filet mignon) with biscuits, mushrooms, onions, peas, salad and fries. Clark helped out first as a dishwasher and later with food prep.

“You would see people from all walks of life,” he said. “It didn’t matter where they were from, what they looked like — everyone was treated the same. That’s how it was. My grandparents treated people with respect and expected everyone in the restaurant to be respectful to others as well.”

Nora Hendrix, the paternal grandmother of musician Jimi Hendrix, worked for Clark’s grandmother at Vie’s.

In 1969, the city came for Clark’s grandparents’ house. The city paid them about $30,000, Clark recalls. So like many others, the family moved to East Vancouver by the PNE fairgrounds.

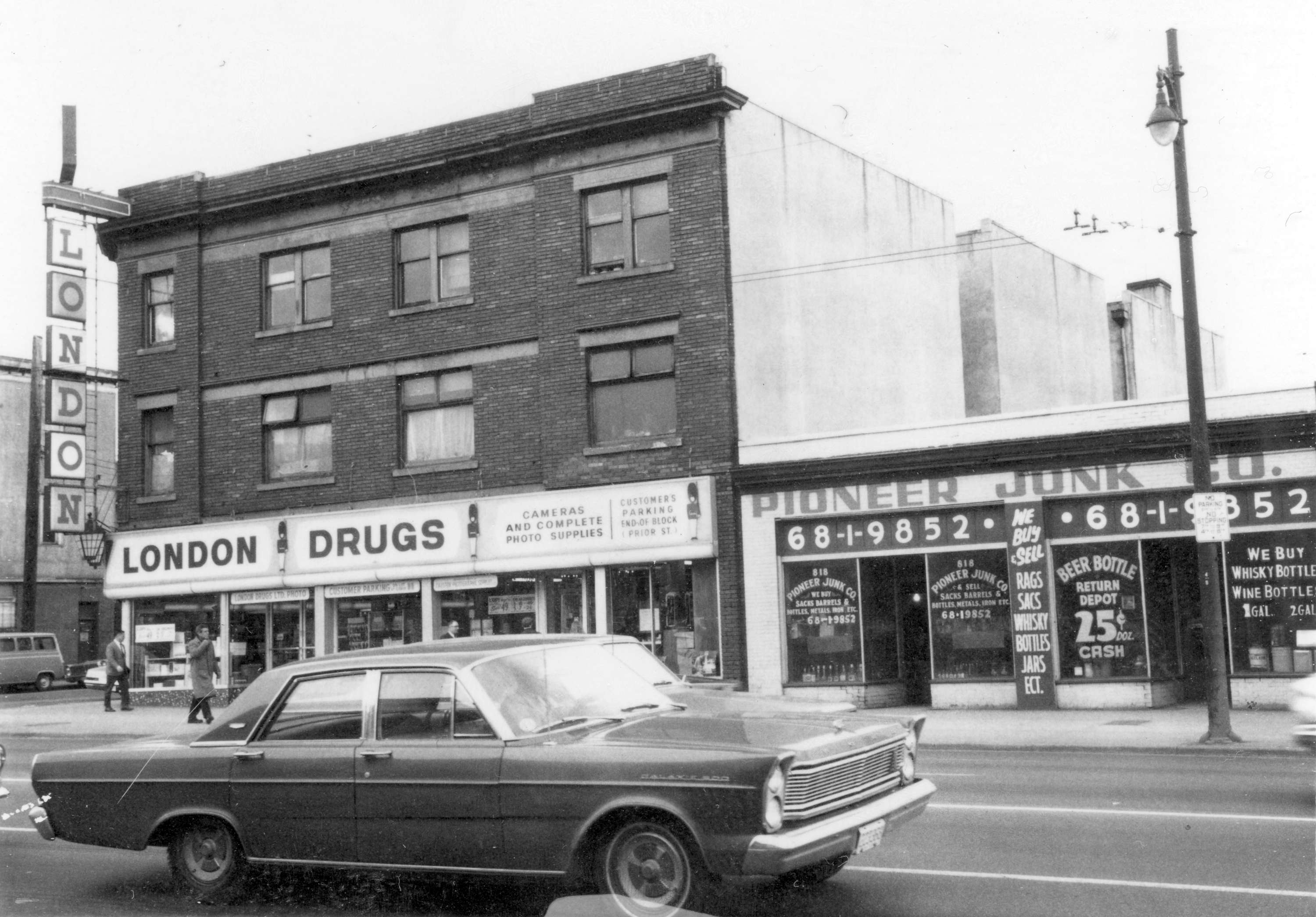

On Main Street corner of Clark’s block was a three-story brick building that belonged to the Chau Luen Society, one of many clan- and village-based immigrant organizations in Chinatown, a few steps north of this building. The first London Drugs was in this building and the society ran the upper floors as a rooming house for the Chinese community. The city expropriated the property for about $112,000.

On the opposite end of the block was Union Laundry, owned by Harry Yuen. He was one of the last holdouts before the city expropriated his property as well. Yuen told the papers that he would “fight off the bulldozers with guns.”

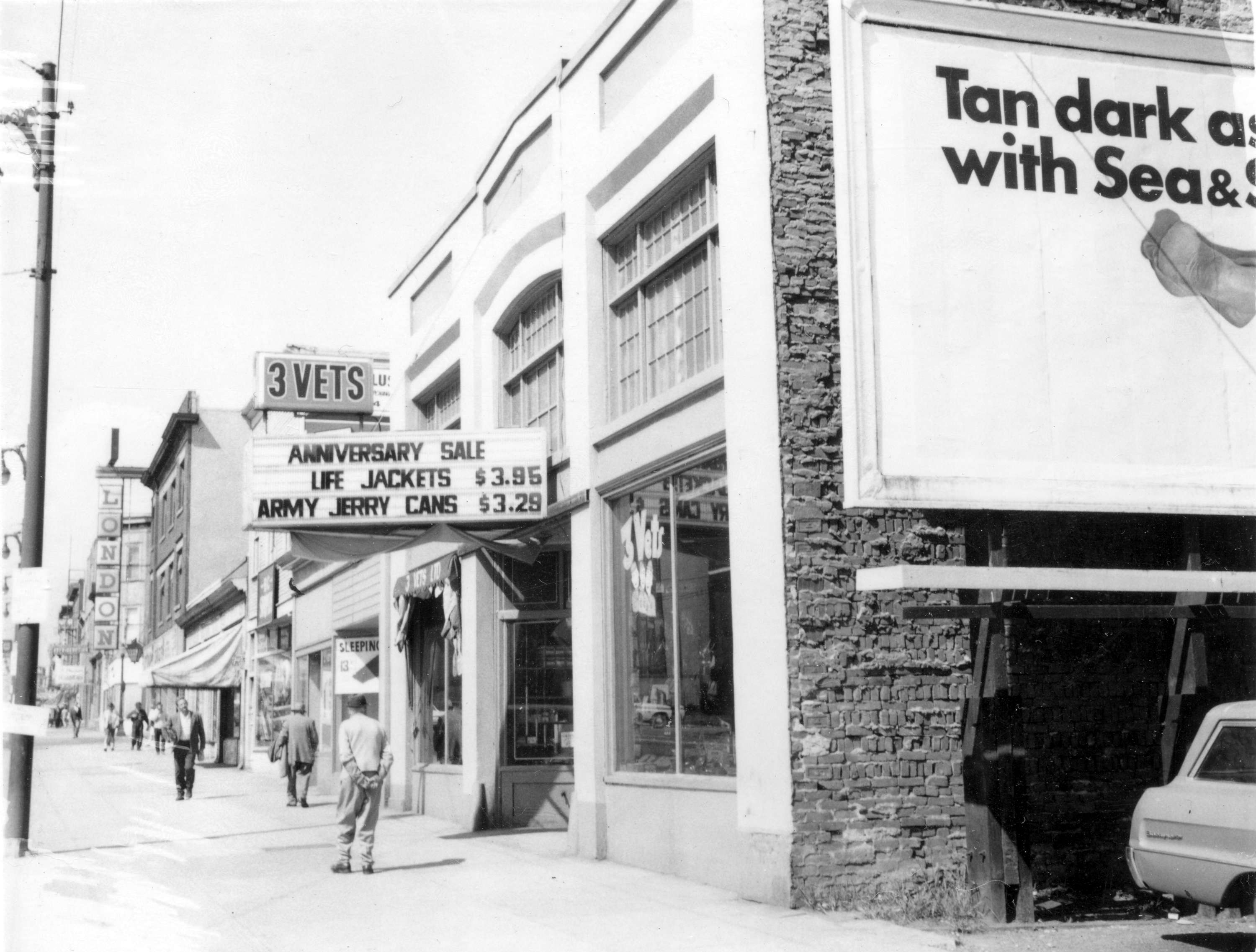

The city salted the earth here. Where Vancouverites once saw shops like Pioneer Junk Co. (Got empty bottles? “25 cents doz. Cash”) and 3 Vets (“Life Jackets $3.95. Army jerry cans $3.29”) they’ll now see the armpits of the viaducts. The viaducts fenced in Chinatown in the south. Polaroids taken by the city’s properties division show some of the homes that were expropriated and demolished: Victorian and Edwardian houses like those surviving in Strathcona today. The images are a record of a missing chunk of Vancouver.

Urban repair

In February, Vancouver city council approved the Northeast False Creek Plan for the largely empty area. The viaducts will be coming down; two city-owned blocks will take their place.

“I didn’t want them up in the first place,” said Mike Harcourt, “so I will be delighted to see them down.” Before he was Vancouver’s mayor or B.C.’s premier, he was a young lawyer who teamed up with local residents to fight urban renewal.

Considering the area’s past, Andy Yan of the Simon Fraser University’s City Program says there are many questions of “spatial justice” for the marginalized communities that once called this area home.

“Is reconciliation a type of development? A change in the practices of development? Who it includes?” he asks. “And how does reconciliation work towards relationships?”

For Vancouver’s Indigenous communities, the city notes that northeast False Creek is on the unceded traditional homelands of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations. Each nation had their own relationship to the False Creek area, including their own place names. The area was heavily used for fishing, harvesting and hunting. The city says it’s working with the nations on how streets and parks are designed. The city also has Indigenous peoples who have relocated to Vancouver from other communities in mind; an Indigenous people’s gathering space is planned.

For Chinese Canadians, the city is working with members of that community on opportunities for public and cultural spaces that nod to the past while meeting the community’s current needs.

The plan also mentions the need to curb speculation and encourage a healthy business mix in Chinatown. New high-end condos have been built and high-end businesses have moved into Chinatown in the past decade, while a number of longtime businesses that catered to the area’s Chinese-speaking seniors and low-income residents have closed.

Protests against upscale and physically out-of-scale condo developments are this generation’s equivalent of the fight against urban renewal.

“The essence of Chinatown should be preserved as much as possible,” Harcourt said.

A program to support “legacy businesses” is being explored by Vancouver and is something San Francisco has created.

For the black community on the former Hogan’s Alley block, there will be a cultural centre, a daycare and non-profit-run social housing. The city is working with the Hogan’s Alley Working Group on this project, and Randy Clark is a member.

“I always think about the families who called that area home, the families whose children have great memories of the area but had to leave under quite deliberate circumstances,” Clark said. “To make something special for our Vancouver community and beyond to learn about the history of the people who lived there, what the community was like and how was special it was… to me, that’s huge.”

Urban renewal fighters Chan and Harcourt are looking forward to having the Downtown Eastside, Chinatown and Strathcona reconnected with the rest of the city and False Creek.

Activism has persisted in this section of the inner city as wealthier residents and the businesses that cater to them move into fragile communities. Development and planning processes remain targets of civic activists. Earlier this year, critics scolded the city for allowing three towers to pierce protected “view cones” of the mountains.

Chan, who remains an advocate of more equitable cities today, has some words for those who continue to fight.

“It’s important to plan a city for everyone who lives in it,” she said. “If you’re passionate about your issues, you should fight for those issues and make sure that you’re included in any policies and plans are being developed, and that the interests of the underdog are always represented.” ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: