Black History Month is officially over. But the study of black history need not be confined to a particular day, week or month of the year. Actor Morgan Freeman is quoted to have said to 60 Minutes journalist Mike Wallace, "You're going to relegate my history to a month?... Which month is White History Month?... Black history is American history." Important as it is to celebrate Black History Month in Canada, we need to recognize the contributions of black communities and individuals as an integral part of Canadian history as well.

When my son was in kindergarten a few years ago, we read about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad, where Canada was the destination for African-American slaves seeking freedom. Now that he's gotten older, he has been ready to hear about the more complicated side of Canada's black history.

Many Canadians don't know about the existence of slavery prior to Confederation in the land that became Canada. Due to a shortage of servants and labourers, New France brought in black slaves from West Africa. The first recorded slave, Olivier Le Jeune, was a boy taken from Madagascar to New France in 1628. A number of books, plays and poems have been inspired by the case of Marie-Joseph Angelique, a Portuguese-born black slave in Montreal who rebelled against being sold by her owner. In 1734, she was convicted of having caused a fire which began in her owner's home and spread to 46 buildings at the time of her escape. Historians have continued to debate whether she was guilty or innocent.

There were slaves living in British areas of what became Canada as well. After the American Revolution, there was a large wave of black immigration to Nova Scotia with the arrival of over 2,000 black Empire Loyalists who had fought for the British. White Empire Loyalist also came, bringing with them about 2,000 slaves to the Maritimes, Lower Canada and Upper Canada. A decade later, due to racist treatment and segregation, nearly 1,200 black Nova Scotians decided to relocate to a settlement in Sierra Leone in 1792. Lawrence Hill's acclaimed novel, The Book of Negroes, vividly depicts the harsh living conditions and discrimination experienced by blacks in Nova Scotia that led many to depart. (The Historica-Dominion Institute has developed a superb teaching guide with a historical timeline that incorporates material from Hill's novel. Available in both official languages, it was distributed to more than 4,500 schools across the country last year and early this year.) Slavery didn't officially end in the British colonies until the British Parliament abolished it in 1834.

Black history in British Columbia

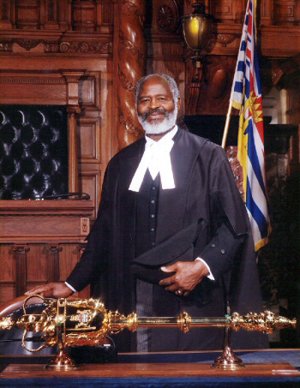

In the territory that became British Columbia, 600 African-Americans came from San Francisco to the west coast in 1858 spurred by the gold rush and a spate of repressive legislation in California. The governor of the British colonies at the time, James Douglas (whose mother was Guyanese) also initially encouraged African-American settlement in B.C. The black population increased over the next few years to about 1,000, establishing businesses, forming the colony's first militia, and participating in civic affairs, as detailed by Crawford Kilian in his book, Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia. (See a video of his talk for Black History Month in Victoria by clicking here.) Mifflin Gibbs, who was elected to Victoria's town council in 1866, became the first elected black politician in Western Canada. However, at the end of the American Civil War, more than half of the black population in B.C. returned to the U.S., although individual black immigrants continued to come to B.C. from the U.S., Britain, the Caribbean, Africa and other parts of Canada. (Profiles of a number of prominent black British Columbians, including Mifflin Gibbs, Rosemary Brown, Harry Jerome and Emery Barnes, are available on the B.C. Black History Awareness Society's website.)

Local author, Wayde Compton, has also written about black history in B.C., with a particular focus on Hogan's Alley, a historic black neighbourhood located in the southwest corner of Strathcona in Vancouver that was eventually obliterated as a result of city hall zoning and planning policies related to urban renewal, which included a proposal to construct a freeway through Chinatown, Hogan's Alley and parts of the Downtown Eastside. (See After Canaan: Essays on Race, Writing, and Region, as well as the comprehensive anthology edited by Compton, Bluesprint: Black British Columbian Literature and Orature.) In this video, Compton talks about Hogan's Alley, about some of its residents, including Jimi Hendrix's paternal grandmother, Nora Hendrix, and about the forces that led to its eradication:

Compton's analysis of the demise of Hogan's Alley has some parallels with the demise of another historic black community on the opposite coast of Canada. The community of Africville, located at the northern tip of the Halifax peninsula in Nova Scotia, was also dismantled in the name of urban renewal. An older community formed by former slaves from the late 1700s onward, Africville was not a neighbourhood integrated within Halifax. Rather, it existed as a segregated community on the city's outskirts, and was denied sewage, fire protection, street lights, water and other basic utilities. Government officials also chose to locate a prison, an infectious disease hospital and garbage dump there. The NFB produced a moving documentary about Africville in 1991 as a tribute to the community and its residents.

Of course, there are black communities that have survived and thrived. Halifax Poet Laureate Shauntay Grant authored a beautifully illustrated picture book for children, Up Home, based on her childhood memories of growing up in North Preston, Nova Scotia. This book was based on one of Grant's spoken word poems and won two Atlantic Book Prizes.

Racism? Here?

When I've talked to my son about the black communities from the past, he has difficulty understanding how or why the municipal governments of Vancouver and Halifax of that time could have made the decisions they did. Racism seems both irrational and unreasonable, and thus incomprehensible to him. It's somehow easier for him to imagine racial segregation going on in the southern U.S. or in South Africa during apartheid.

Of course, the powerful iconic images and narratives of the American civil rights movement are inescapable. As a result, many Canadians know more about the U.S. civil rights movement than the struggles for civil rights here in Canada. My son already knows about Rosa Parks and her refusal to give up her seat in the front of the coloured section of the bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama. But I've also tried to tell him about Viola Desmond, a black businesswoman from Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1946, a year before Rosa Parks' protest in the U.S., Desmond bought a ticket to watch a movie at the Roseland Theatre in New Glasgow after her car broke down and needed time for repair. Because the theatre was segregated, she was only permitted to sit in the balcony. She tried to sit downstairs, but was arrested, forcibly removed, jailed, fined and sentenced to 30 days imprisonment. She managed to successfully appeal on a technicality, but the community support and public attention the case garnered eventually led to by the repeal of segregation laws in Nova Scotia in 1954. Exclusion or segregation of blacks, as well as of other groups, whether encoded in legislation and bylaws or practiced informally, occurred in various settings across Canada.

I want my son to know about Canada's black heroes and pioneers, but I also want him to realize that they overcame overt racism and discrimination, in part because I know those attitudes persist in our lifetime, whether in the same form or another. I still remember how my alarmed paternal grandmother rapidly flipped past the photos of me taken with an African-American classmate when I was a student overseas. Or an aunt's initial disapproval 12 years ago when my cousin married an African-American woman. I want to ensure my son is able to identify and reject those overt or covert prejudices while understanding some of the context and history behind them, in the hope that he and his generation will be able to form an unshakeable core sense of justice and equality so that the battles of the past will not need to be fought again.

[Tags: Rights + Justice.] ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: