Housing unaffordability is a major problem in attractive and economically successful cities like Vancouver and Victoria. Many households spend more on housing than is considered affordable, and many people would like to live in these cities but cannot due to insufficient housing supply.

But it is important to be smart when evaluating housing problems. How affordability is defined and measured can affect what solutions are implemented. Measured one way, a particular solution may seem effective and beneficial. Measured another, it may seem wasteful and harmful overall.

One often-cited source of housing cost data, the International Housing Affordability Survey (IHAS) by Demographia, a U.S. think tank, argues that housing unaffordability is caused by urban containment policies, such as our Agricultural Land Reserve, and can be solved by allowing more urban sprawl. This research is widely reported on by media, such as the Guardian, the New York Times and the Globe and Mail, among others.

Most of these news articles simply repeat the IHAS press release with little critical analysis. My new report, “True Affordability: Critiquing the International Housing Affordability Survey” (full report here) examines its analysis methods and recommendations.

My conclusion: the Survey is propaganda, intended to support a political agenda rather than provide objective guidance.

The Survey’s methods are unsupported by objective research and transparent analysis. The authors, Wendell Cox and Hugh Pavletich, are either very poor researchers or are misrepresenting key issues to advance a pro-sprawl agenda. They have failed to respond to legitimate criticism, and their work lacks peer review.

Here is my analysis, which identifies significant problems with its analysis methods which bias results:

-

The Survey evaluates housing affordability using “median multiple,” which measure the ratio of median house prices to median household incomes. This only considers house purchase prices, ignoring other shelter costs such as maintenance, utilities and property taxes, and it ignores transportation costs. The costs the Survey considers are smaller on average than the costs it ignores. Since detached, suburban houses tend to have higher maintenance, utility and transport costs, this exaggerates the affordability of urban expansion and underestimates the affordability of more compact development.

-

The Survey overlooks or under-samples affordable housing types including secondary suites, rentals, subsidized housing and condominiums. This exaggerates unaffordability where such housing is common.

-

It includes a limited set of regions. In some countries it includes both small and large cities, but in Asia it only includes large and expensive cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo. This exaggerates unaffordability in those countries.

-

It fails to account for factors that affect regional affordability such as population and economic growth, incomes and geographic constraints. This exaggerates unaffordability in attractive, economically successful and geographically constrained regions.

-

It measures entire regions, ignoring within-region affordability variations. Central neighbourhoods are generally most affordable overall, considering total housing and transportation costs, and offer other benefits such as commute time savings and health benefits.

These biases make detached urban-fringe housing seem more affordable, and compact infill housing seem less affordable, than households actually experience.

Measuring true affordability

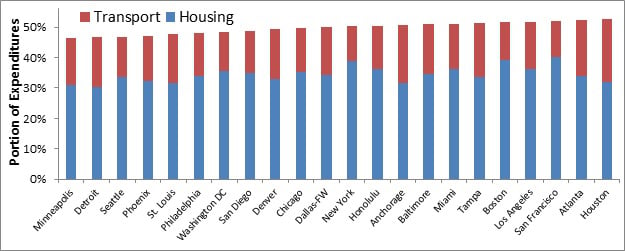

Affordability refers to a consumer’s ability to purchase basic goods such as food, housing, transportation and healthcare. Extensive literature considers how best to measure affordability. Since housing is usually the largest expenditure, affordability was originally defined as households being able to spend up to 30 per cent of their budgets on housing, but since households often make trade-offs between housing and transport costs, for example, between cheaper urban-fringe housing or more expensive central-area housing, many experts now recommend defining it as households spending no more than 45 per cent of their budgets on housing and transport combined

The IHAS only considers house purchase prices, ignoring other factors such as utilities, maintenance and transportation costs. As a result, it ranks sprawled cities such as Atlanta and Houston as more affordable than Seattle and Washington, D.C., although when evaluated using consumer expenditure data, the rank reverses. The sprawled regions’ low housing costs are more than offset by their higher maintenance, utility and transport costs, making the sprawled regions the least affordable of the 22 regions for data areas available, as indicated below.

Sprawl is not a saviour

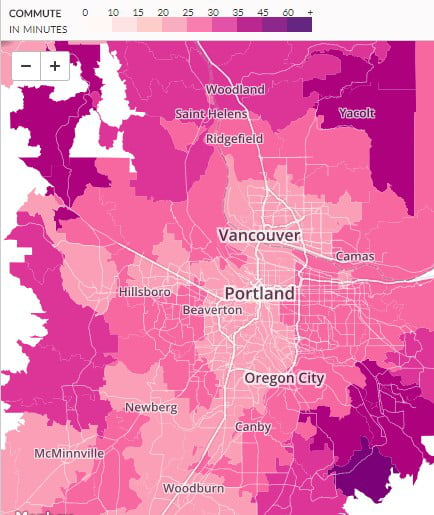

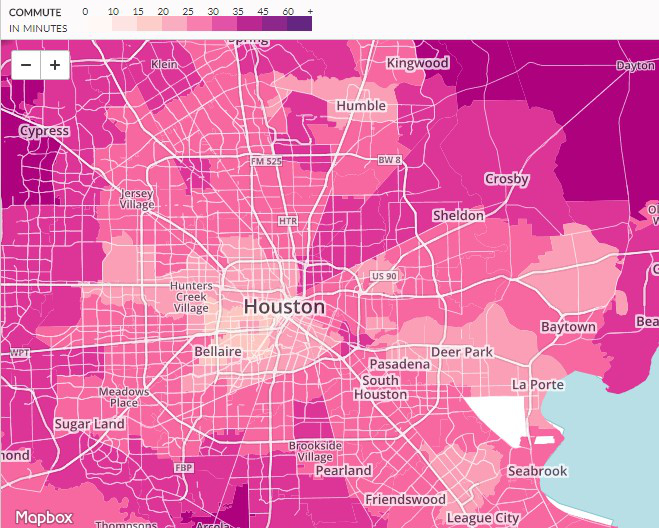

The Survey also ignores the benefits of living in a walkable urban neighbourhood. It claims that car-oriented sprawl reduces travel time costs, but within virtually all regions, more central neighbourhood residents have better access to jobs and services, and shorter duration commutes than urban fringe residents, as indicated below.

This is particularly true for non-drivers, who have far more independent mobility and therefore greater economic opportunities in central urban neighbourhoods. The Survey ignores these benefits.

Urbanists call development that encourages housing and transportation options smart growth, which the IHAS criticizes, claiming that it consists primarily of urban containment regulations. But smart growth actually includes a variety of strategies, many of which reduce regulations and increase affordability, for example, by allowing more housing types such as townhouses and apartments, and reducing parking requirements by allowing transportation other than driving.

The Survey claims with great certainty but no real evidence that urban containment policies are the primary cause of urban housing price increases. In fact, even studies it cites indicate that restrictions on urban infill (redevelopment) are much more common and costly than urban expansion restrictions, and therefore a much larger cause of unaffordability.

Reducing these constraints on infill, so more households can find suitable housing in walkable urban neighbourhoods, is the key to creating truly inclusive communities.

Expansion may be appropriate in cities with abundant land nearby, but incurs high costs to residents and communities. As a result, there are good reasons to favour infill with policies that increase housing in existing urban areas.

The Survey advocates low-density urban expansion, but ignores the additional costs of sprawl to residents and communities.

The Survey also ignores the mobility needs of people who cannot, should not or prefer not to drive, therefore also ignoring the isolation and higher transport costs they experience in car-dependent, urban-fringe areas.

The Survey claims incorrectly that sprawl benefits disadvantaged people. Good research indicates the opposite: physically, economically and socially disadvantaged people have more independence, better economic opportunities, and better outcomes in walkable urban neighbourhoods than in car-dependent suburbia.

Although the IHAS is presented as objective research, it does not reflect professional standards: its analysis is not transparent, it misrepresents key issues, fails to respond to legitimate criticism and lacks peer review.

To anyone using IHAS data: be warned, the analysis is sloppy, the recommendations unjustified and the authors lack credibility.

Housing affordability is both a great challenge and a great opportunity. With comprehensive affordability analysis and smart, integrated solutions we can create communities that truly provide economic opportunity, freedom and happiness. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: