“We ate together in the kitchen every day at 7 p.m.,” Fiona Zeng said.

Zeng and her brother grew up with their grandmother at home. She didn’t think anything of it. Many of her friends in the south Vancouver neighbourhood of Fraserview had three generations of family in one house.

“It was a totally normal thing,” said Zeng, who grew up in the early 2000s.

There were some challenges, like noise or her brother having to share a room with their parents, but these became part of everyday life.

Her family bought the house in 2001 for $300,000, cheaper than today’s standards, but their household arrangement helped make things more affordable. They didn’t need to spend money on child care or senior care and could rent out the basement for extra income.

In a majority-immigrant neighbourhood like Fraserview, families helped each other out. Parents and grandparents from different families organized to walk neighbourhood children from home to school and back. They created a system that included taking turns to pack lunch for all the kids.

“It would be Chinese food. Rice with a vegetable, normally winter melon, and some sort of meat,” Zeng said.

There have been headlines about people “hacking” expensive Canadian housing markets with creative solutions: individuals developing cohousing complexes or roommates sharing mansions for low rents.

But there’s a kind of household that’s been making do by sharing for a long time: multigenerational households like Zeng’s. It’s one way Vancouver immigrants have achieved affordable homeownership for decades.

Today, multigenerational family households are the fastest growing type of household in Canada. They increased by 38 per cent from 2001 to 2016, while total households only increased 22 per cent in that time, according to census data.

Canadians in multigenerational family households number 2.2 million; that’s six per cent of Canadians living in private households.

Households like the Zengs challenge longtime North American ideas about family and what our neighbourhoods look like: not all families are “nuclear families.” Sometimes members of an “extended family” are a part of a household and not all “single-family houses” are home to a single family of parents and their kids.

“There’s this imagination and then there’s the reality,” said Andy Yan, the director of Simon Fraser University’s City Program. “The reality is we’re an immigrant-driven country with people from a number of cultures.”

Immigrant and working class people did not shape mainstream ideas of how households and neighbourhoods should look like in North America. As a result, the different ways they created home without the help of public policy were often ignored.

Sociocultural trends, survival tactics

Multigenerational households are more common with immigrant and Indigenous populations; the growth of both these groups is fueling the rise of this household arrangement, according to Statistics Canada.

Grandparents living with their children and grandchildren (14 and under, according to the census definition) are most common in urban centres with high ethnocultural diversity. Abbotsford-Mission is at the top (21 per cent of families with children), then Vancouver (16 per cent) and Toronto (15 per cent).

Live-in grandparents are the least common in Quebec’s urban centres; they’re the rarest in Quebec City, with grandparents in only two per cent of families with children. Yan notes that Quebec has government-sponsored daycare and housing that is largely affordable for families with children on local incomes compared to Vancouver.

Jian Zeng, Fiona’s father, “never had a thought about” whether his five-person multi-family household was a phenomenon to be examined.

“It’s a natural thing for us people from China,” he said. He was born in Nanjing, and his wife’s family was from Hong Kong and Shanghai.

The idea of filial piety, respect for parents and elders, is engrained in many eastern cultures, along with prioritizing family over the individual. For some, this has translated to adult children caring for their aging parents by inviting them to live with them and their children. This practice contrasts with North American ideas of individual independence, which involve markers of maturity like living apart from family.

Keeping extended immigrant relatives in one household is also comforting for relatives like grandparents if their English is limited and they don’t know anyone in the new country.

For the Fungs, a family of four who live a few blocks south of the Zengs, the grandparents moved in simply because they were lonely.

Aside from social or cultural reasons, multigenerational households were and are a survival tactic in expensive housing markets in Vancouver, Yan says.

Extended families living together can save on expenses like food or leisure items like Netflix. But multiple household maintainers also share the rent or mortgage. Having extra adult relatives in a household is more than a matter of having someone to babysit.

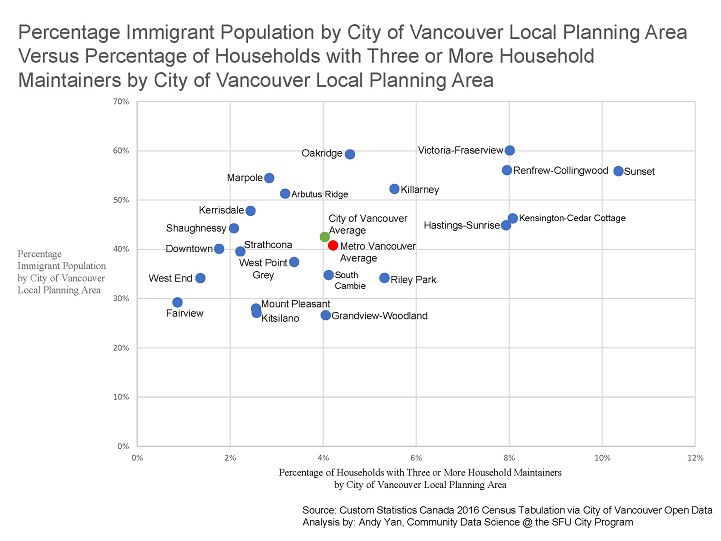

An analysis of 2016 census data by Yan reveals that Vancouver neighbourhoods with majority-immigrant populations — like Sunset, Renfrew-Collingwood and Victoria-Fraserview on the East Side — are among those with the highest percentages of three or more maintainers per household in Vancouver. In Sunset, one in 10 households have three or maintainers.

These are neighbourhoods with high numbers of detached houses. Census data reveals that households with three or more maintainers are rarest in vertical neighbourhoods with high-rises like Downtown and the West End, making up only two and one per cent of households, respectively.

Homeownership is also a benefit for multigenerational immigrant households because it’s hard for immigrants and large families to find landlords willing to rent to them.

When density meant poverty

Naveen Girn — who curates intercultural dialogues and works as the director of community relations at the Vancouver mayor’s office — grew up in a house on the city’s East Side in the 1980s. The household included his immediate family and his grandmother.

Despite it being a detached house, like the Zengs’ home, it was not “single family.”

“It was an anchor point for a lot of family members,” Girn said. His parents were from Fiji, and many relatives would stay at their home. “That was one of the richest things about growing up in that house.” He has fond memories of playing with live-in cousins.

Family albums and video remain a record of the strong ties his parents had with visitors.

“There are photos my family has of an airline pilot who came over to have a meal before going back to Fiji again.”

The Girns occasionally rented out their ground floor. They lived in a Vancouver Special, a stucco box house with two identical levels that was popular with immigrants because of its size and affordability. Many working-class immigrants who owned Vancouver Specials had housing arrangements like the Girns.

But this was an era when density was associated with poverty. Post-war, middle and upper-class whites wanted to escape crowded cities for the suburbs. A good home was a spacious house with a large yard. These were also homogenous communities with little diversity.

In Vancouver, the bias of keeping houses “single-family” and neighbourhoods roomy was so strong that the city stopped approving Vancouver Specials in the 1980s. Mainstream city planners believed that extra tenants and extended relatives in a house would crowd neighbourhoods for the worse.

Many forget now that concerns about the lack of affordable housing were raised in 1960s Vancouver. But even though Vancouver specials and multigenerational households offered financial and social solutions, the housing legacy of working-class newcomers remained out of the mainstream.

Function over form

Today in Vancouver and other geographically challenged cities struggling with housing affordability, mainstream attitudes toward detached houses has shifted. Roomy houses and neighbourhoods were thought of as good things; now, many planners think they hog too much room.

Vancouver has been densifying its neighbourhoods of detached houses. True “single-family” houses are declining as renters share and the city welcomes basement suites and infills like laneway houses.

But multigenerational immigrant families have made creative, dense use of detached houses to their advantage for decades — no policy required. Welcoming extended relatives into the household helps with child and senior care. Another extended relative in the household could also mean another household retainer. Sparing a floor means it can be rented out for income.

Ethnocentricism and “single-family” bias once blinded planners from seeing the benefits of multigenerational households. Today, SFU’s Yan says we shouldn’t let blaming the form of detached houses for inefficiency blind us from seeing what they can teach us.

“We need to look at the function of what’s happening in single-family houses and how that might be replicated,” he said.

Of course, not all families have the benefit of extended relatives, and not all families can attain homeownership. And in places like Vancouver, houses are becoming rarer and more expensive.

But cities still need family housing. And how family is defined, how family-friendly housing is defined, how social networks are fostered and how buildings are organized and designed are important questions to explore as places like Vancouver densify and diversify.

It’s not just size that matters, says Yan. Vancouver and New Westminster have “family-friendly” housing policies that mandate a certain percentage of three-bedroom units in new developments, which are rare in the region, but they don’t address affordability. Design and amenities are important, too.

“It really is in how these four elements interplay [size, affordability, design, amenities] that determine the success or failure of family housing,” he said. “A three-bedroom apartment that’s poorly designed, unbelievably expensive and with no amenities won’t help with the situation.”

Families like the Zengs managed to score on all four by sharing a house.

Fiona Zeng, 21, is back living with her family again today, while finishing university.

She believes culture has a role to play in her family living under one roof and understands it might be unusual to some. But the fact that housing is getting expensive for more people might help them see that it’s one more model of how to get by in a city like Vancouver.

“I think it really is rooted in Asian culture,” she said. “But it happens to be convenient.” ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: