It was spring break 2014, and Pam Turgeon was lounging poolside with her daughter, Shadia, in Scottsdale, Arizona. As her kids splashed around in the sun, Shadia scrolled through her phone.

“Mom,” she said. “You’re not going to believe this.”

Pam looked up. “What?”

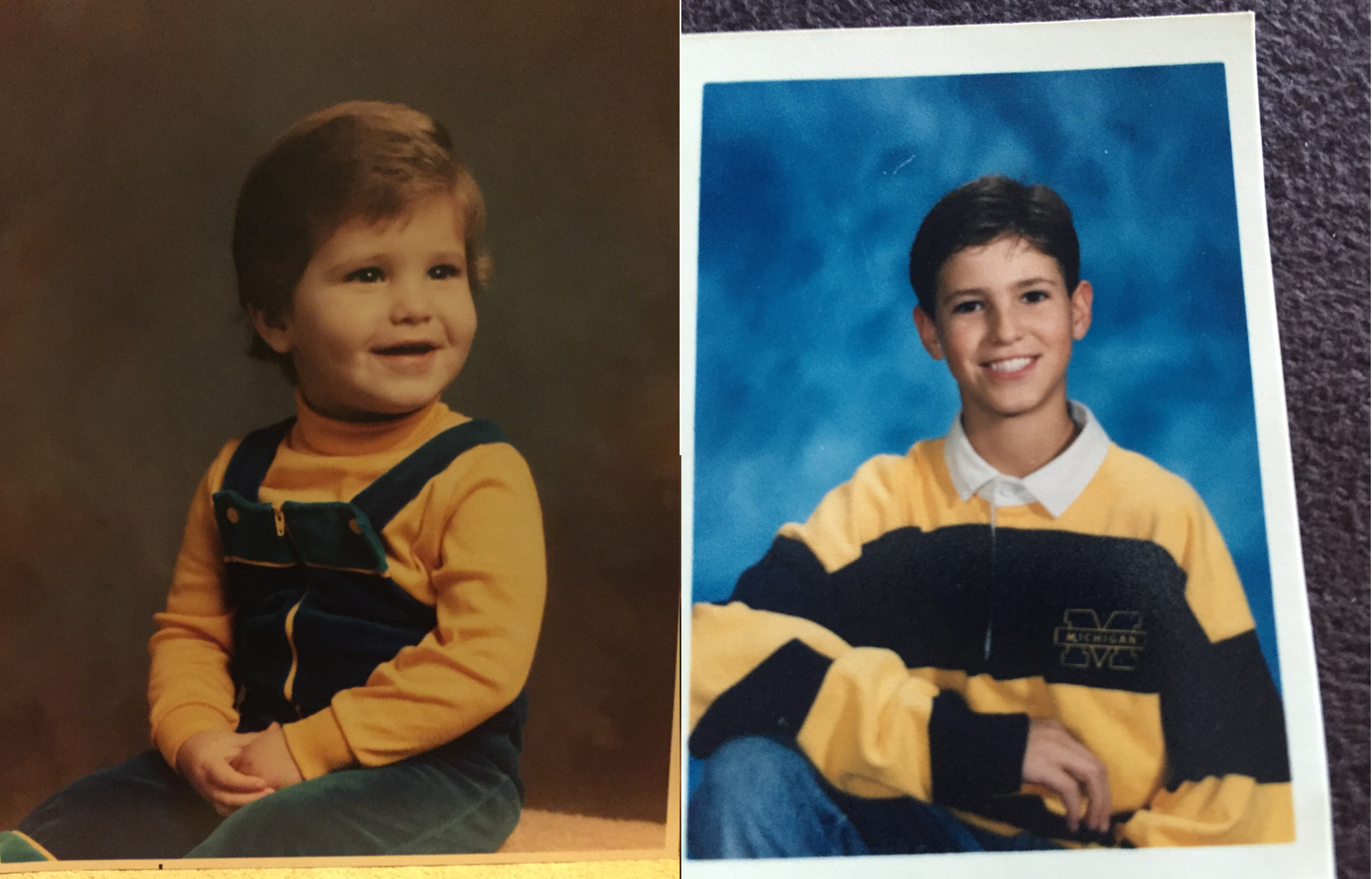

“Ryan’s missing.”

It seemed impossible. Ryan Turgeon had recently started a new contract as an instructor at a drilling school in Torremolinos, a city in the province of Malaga, Spain. He’d been working in the oil industry as a cyber driller since he’d graduated from high school in 2001, and was dispatched to work on tanker ships around the world. He’d typically work a 30-day “hitch” followed by a 30-day break at home in Leduc, Alberta and later Kelowna, B.C.

Dense bursts of work followed cathartic weeks of time off. Ryan would come home in a hail of celebration, arms loaded with souvenirs for his nieces. He’d enjoy long stretches of nights out with friends, and could often be found behind the turntables at parties as a hobbyist DJ. It was always a happy reunion when he came home, and he was rarely out of touch with his family while out on the rigs.

They knew him as an affectionate, happy person who would go out of his way to lend a hand to anyone who needed it.

In recent weeks, though, Shadia found it odd that she hadn’t heard from him after sending her brother a care package for his birthday. And now the drilling school had lost track of him. They emailed her to say that he seemed out of sorts when he arrived in the classroom one Monday morning, so his workmates sent him home, telling him to take the day off.

“Nobody saw him after that,” his mother says.

Pam left Scottsdale for Vancouver, then Spain the next day. Working with local police, she eventually found her son on his 31st birthday at a mental institution, heavily medicated on drugs he didn’t recognize because he couldn’t understand Spanish, and neither could she.

Ryan couldn’t remember how he’d gotten there. But according to authorities, he’d been pulled out of the Mediterranean Sea.

He’d experienced a mania, as far as anyone knew, the first such episode of his life.

‘We just want you to get better’

Once home in Kelowna, B.C., doctors diagnosed him with Bipolar 1, a bipolar spectrum disorder characterized by the occurring of at least one manic episode featuring racing thoughts, accelerated speech, and a lack of impulse control.

All of this was new. Mental illness was never previously part of Ryan’s life as he experienced it, but doctors suggested it might have started manifesting when he was a teenager. They prescribed him a host of medications to manage his new diagnosis, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-anxiety medications, and mood stabilizers.

Those drugs flattened him out, Pam remembers. His usual vibrancy faded away.

“My son would come upstairs and he’d have no emotion on his face,” she says. “Or his lip would be sagged down from the medication.”

But this was all part of a new plan. Ryan would take time off work to recover, and he’d live in the basement of his parents’ west Kelowna home until he got back on his feet. It wasn’t an ideal arrangement, but Ryan was close to his family and they were there for him. Plus, he was the one who always wanted to make his family happy.

The situation weighed on him. But Ryan’s didn’t need to be cause for shame. Living with a parent is now the most common living arrangement for young adults for the first time on record, according to 2016 research from the Pew Research Center.

It’s a new reality, but it’s not what many people want. “If you don’t have a job and you’re that age, living with your parents — it’s a really big issue, especially in Canadian culture,” Pam says.

“We kept saying, ‘Lookit, we have a big house, it’s no big deal. We just want you to get better. And when you get better, you’ll buy your own place and you’ll be back on your feet.’

“But he couldn’t see past what he’d already lost.”

Ryan struggled with depression throughout the time he was back in his parents’ home. “If it wasn’t the bipolar medication, it was depression because of his situation,” Pam says. “He was depressed because he didn’t have work.” On top of that, his new medications deepened his dark state.

“He would say to me, ‘Every day, Mom, I think of killing myself. I would never do it. But I think about it. Because whatever drugs they’re giving me, this is how I feel,’” Pam says. “And I used to think, how awful would that be in your head every day?”

The thoughts gnawed at him. He’d blow off steam by going out. Throughout his working life, he partied hard and his friends did the same, drinking and doing lines of cocaine at parties. He was characteristically generous, and his income would amplify that. Pam estimates that he made about $20,000 to $25,0000 a month overseas, an amount, she admits, is “a downfall, too.”

Ryan’s parents had tried to talk him out of working in oil, particularly his father, who also works on rigs overseas. “My husband Mike has always been gone. So I raised the kids on my own, basically,” Pam says. She and Mike tried to convince Ryan to pursue more family-friendly work as an airline technician instead.

“But I mean,” she adds, “Once he got a taste of the money, then it was like no turning back.”

He wrestled with drinking, drugs, and attempting sobriety while in his parents’ house in Kelowna. Eventually as 2014 ran out the clock, he asked his family for help. They took him to a private rehabilitation centre in Salmon Arm. Pam dropped him off a few days before Christmas, and he stayed there for two months. It cost almost $20,000.

When he returned home in early 2015, he took new a run at sobriety. He attended meetings with Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, connected with a sponsor he admired, and started CrossFit again. He took on some landscaping work. Things seemed like they were getting back on track.

Later that year, however, a date turned into a bender. Ryan returned home, more depressed than before.

His final months of life, December 2015 and January 2016, were marbled with depression.

“The week before he died. I said, ‘Ryan just seems like he’s really down.’ And everybody was like, ‘You’re doing what you can do. You’re doing the best,’” Pam remembers. But she knew something was off, and she couldn’t shake it.

She accompanied Ryan to his doctor’s appointment that week. “I said to the doctor, ‘Is there not another rehab or some kind of facility other than paying $20,000 that people can go to?’ And he said, ‘No,’” she remembers.

“And that’s sad to me. Because not everybody has $20,000 sitting around that can pay.”

‘A very big, big void’

Pam says Ryan needed better care after rehabilitation than he was able to receive, like addiction aftercare and the 12 sessions of post-rehab counselling that were supposed to happen but never did.

He was a dedicated AA and NA attendee, and capable of doing the work to get well. He had a family to support him. But it wasn’t enough.

It was Monday morning on Feb. 1, 2016 when Pam finished a FaceTime call with a friend in Texas. She went downstairs to see if Ryan was up. The bedroom door was locked when she knocked. After breaking through, she found him lying on his bedroom floor, unresponsive.

The coroner’s report says that Ryan died accidentally of an illicit drug overdose. Cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl were in his system.

“It is unlikely that Mr. Turgeon was aware that the drugs he consumed contained fentanyl,” wrote coroner Susan Barth. “There is no evidence of foul play or suicide.”

Ryan was one of 47 people who died of illicit drug overdoses in Kelowna last year. Twenty-four more died in the first three months of 2017. After Vancouver, Surrey, and Victoria, Kelowna holds the fourth-highest number of overdose deaths in B.C.

“If this was a SARS outbreak or Ebola like last year, the government would be saying, ‘This is a state of emergency. You need to do something.’ But because these are drug overdoses, it’s like this never-ending time clock that’s never getting to the time,” Pam says. “How many more people have to die?”

Pam and Ryan were close. She misses him terribly. “It’s a very big, big void in our family’s life. I will never be the same,” she says.

“Ryan always was the person that was willing to help with everything. He was kind hearted. He loved his family beyond words.”

Her clearest memories of him, she says, are of “a beautiful, kind individual who just lost his way.”

She wishes they had more time together. She wanted badly for him to get well and back on his feet.

On Sunday night, January 31, they had dinner together at home. Ryan took a bowl of chips and a glass of water from the kitchen before heading down to the basement for the evening.

Ryan said goodnight to his mother, and asked her to wake him if he wasn’t up by 9:30 the next morning.

By 9:36 a.m. on Monday, he couldn’t be revived. ![]()

Read more: Health, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: